Researchers Calculated a Whale Shark’s Age Based on Cold War-Era Bomb Tests

Nuclear bomb tests caused a spike in a radioactive form of carbon that accumulated in living things

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/2d/ea2d5659-dd56-4f07-bfe0-bdba327aeb0c/2020_april7_whaleshark.jpg)

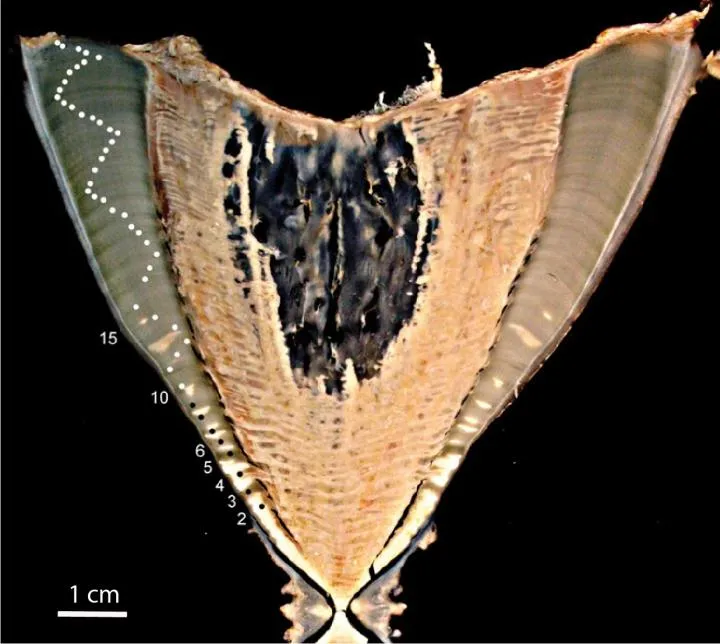

Whale sharks are the world’s largest fish, recognizable by their white-speckled and striped backs. But as whale sharks age, they also gain stripes on their vertebrae.

The layers, called growth bands, build up like the rings in a tree trunk, so the older a whale shark is, the more bands they have. Now, by using the radioactive chemical signature left behind by Cold War-era nuclear bomb tests, researchers have definitively decoded the big fishes’ bands to figure out how long they live.

The research, published on Monday in Frontiers in Marine Science, settles an ongoing debate over how long it takes each growth band to form; experts previously suggested either 6 or 12 months per band. But getting it right has implications for whale shark conservation strategies. The new evidence points to the longer end of the previous estimates: each band takes about one year to form. And, knowing that, the researchers found that the giant sharks can live to at least 50 years old.

“Basically what we showed is we have a time stamp within the vertebrae,” Mark Meekan, a biologist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, tells Liz Langley at National Geographic. “We count the bands from there, and they appear to be annual.”

The researchers analyzed vertebrae collected from a whale shark caught in a Taiwan fishery before 2007, when the fishery closed, and another whale shark that was stranded onshore in Pakistan in 2012.

The “time stamp” comes from a radioactive form of carbon that occurs naturally in low levels called carbon-14. It’s used in carbon dating of archaeological artifacts because its radioactive decay is slow and predictable.

Starting in about 1955, countries, including the United States, began testing nuclear weapons by detonating them high in the atmosphere. The tests about doubled the amount of carbon-14 in the air, which eventually settled in the ocean, where it became embedded in marine animals from shells to sharks. About 20 years ago, study co-author Steven Campana of the University of Iceland developed a method to figure out shark ages using the carbon-14 in their cartilage skeletons.

Using this method, the team found that based on vertebrae stripes, a 32-foot-long whale shark would be about 50 years old. But whale sharks can grow up to 60 feet long, so they may live much longer.

For conservation, “it makes a big difference whether they are fast-growing and short-lived, or slow-growing and long-lived,” Campana tells New Scientist’s Michael Le Page. Long-lived, slow-growing animals take longer to recover from population loss.

“This study is really important because it gets rid of some of those questions about the age and growth patterns of whale sharks,” Oregon State University shark specialist Taylor Chapple, who wasn’t involved in the new study, tells National Geographic. Having “real data from real animals adds a really a critical piece of information to how we globally manage whale sharks.”

As Meekan writes in the Conversation, whale sharks are endangered and face threats from fishing and boat strikes. Whale sharks spend their days basking in the sun near the surface of the water, putting them at high risk of injuries from the propellers of passing boats.

“Whale shark populations take a very long time to recover from over-harvesting,” Meekan writes. “Governments and management agencies must work together to ensure this iconic animal persists in tropical oceans - for both the future of the species, and the many communities whose livelihoods depend on whale shark ecotourism.”