In one of the most iconic images by the pioneering photographer Robert Frank, passengers peer out from a trolley in New Orleans, their expressions vivid and unposed. A woman scowls into the camera, a gesticulating child appears tetchy and—toward the back of the trolley—a black man and woman gaze out of the windows. The 1955 photo is dark, gritty, unsettling—so different from the pristine, optimistic images that American photographers produced in the post-war period.

Frank, who died on Monday at the age of 94, looked at the country through the critical eyes of an outsider. Originally from Switzerland, he travelled across the United States taking photos of factory workers, prostitutes, cross-dressers, cowboys and Americans of all stripes. He rarely spoke to his subjects, but possessed an uncanny ability to capture the alienation, poverty and racism that rippled throughout his adopted homeland. Frank’s 1958 book The Americans, which assembled 83 photos taken during his cross-country tour, had “a profound impact on the art of photography [and] changed the course of American photography,” says Sarah Greenough, senior curator and head of the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art.

“I was tired of romanticism,” Frank once said, according to Andrew Marton of the Washington Post. “I wanted to present what I saw, pure and simple.”

Born in Zurich in 1924, Frank was the son of affluent Jewish parents, reports Philip Gefter of the New York Times. Switzerland’s neutrality during World War II shielded Frank and his family from the atrocities of the Nazi regime, and Frank was able to apprentice with photographers and graphic desingers in Zurich, Geneva and Basel. In 1947, according to David Henry of Bloomberg, he sailed to New York and began working as a fashion photographer for Harper’s Bazaar.

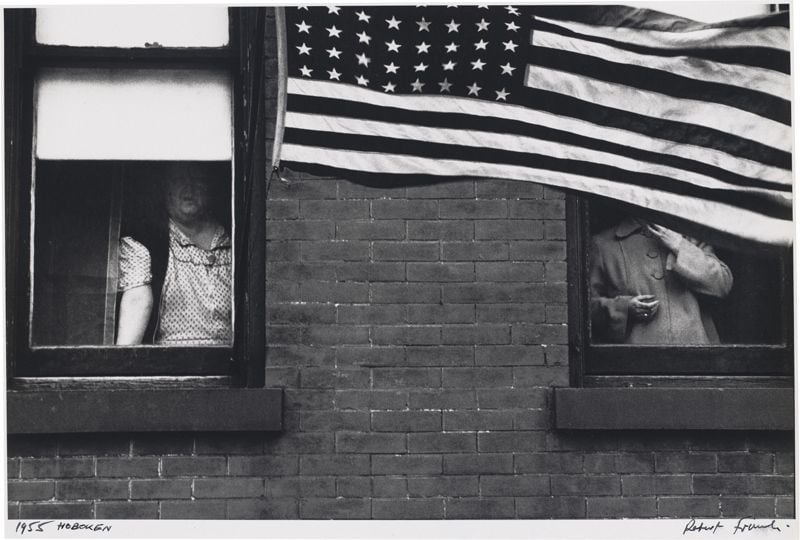

Alexey Brodovitch, the magazine’s art director, was among several influential figures who later wrote recommendations for Frank when he applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955. The application was successful, allowing Frank to embark on the trailblazing journey that would lead to The Americans. Sometimes with his wife, the artist Mary Frank, and two children in tow, Frank drove 10,000 miles, taking some 27,000 images of the scenes he saw along the way: A black woman holding a white baby in Charleston, a gaggle of onlookers at a movie premiere in Hollywood, two women peeking out at a parade in New Jersey, the face of one of them obscured by an American flag.

The images weren’t meticulously composed, instead appearing as though they had been shot from the hip or while on the move. And they conveyed unpalatable realities that other photographers typically did not confront. “Americans at the time had seen themselves through the popular media, Life, Look magazine and other illustrated magazines of the period,” says Greenough. “They really projected a simplistic, optimistic and rosy picture of American life. With the publication of [The Americans], Frank revealed these profound problems within American society and made it impossible to overlook them.”

The book, which boasted an introduction by Jack Kerouac, was not initially well-received; the magazine Popular Photography, for instance, called it a “a wart-covered picture of America by a joyless man,” according to Marton. But younger generations of photographers soon embraced Frank’s raw, uncompromising style, and by 1969, when a later reprint was issued, The Americans was starting to be seen as one of the 20th century’s most important works of photography.

“It encouraged a new generation of photographers to literally take road trips in homage, to try to do what Frank did,” Greenough says. “Which is to … reveal what he thought was the strengths and beauty of the country, but also its issues.”

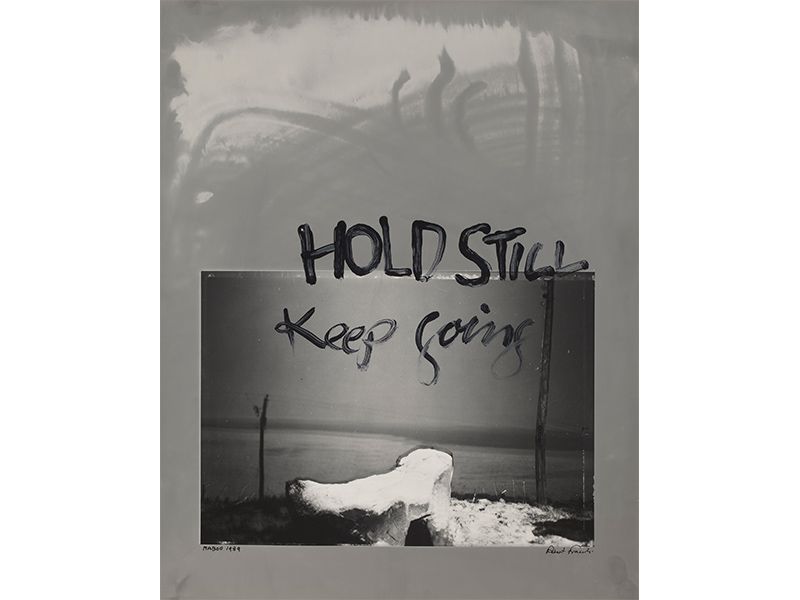

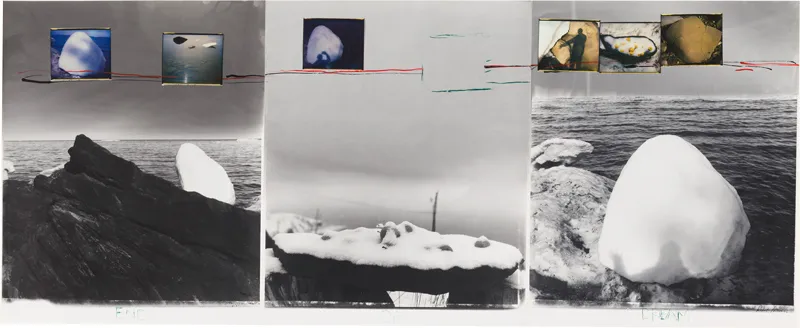

Ever the restless artist, Frank turned his attention to film in the wake of The Americans, teaming up with Beat movement figures like Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, and even documenting a Rolling Stones tour. The deaths of his daughter in 1974 and son in 1994 would shape his later photography, which “took on a darker character, and he began to merge images together or add scratches or words to his prints,” writes Marton.

In the catalogue for a 2009 exhibition of Frank’s work at the National Gallery of Art, Greenough wrote that Frank’s photographs exposed “a culture deeply riddled by racism, alienation, and isolation” and “a people emasculated by politicians fatuous and distant at best.” Those descriptors, some might very well argue, continue to ring true today.

“They were problems then and they are problems now, we cannot simply overlook them,” Greenough says. “We must as a society come to terms with them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/e4/c8e4e195-96c4-4a8d-96ce-8299502f211d/c15302_sbd-resized.jpg)