Pterosaur Tooth Found in Rare Ancient Squid Fossil

A tooth embedded in prehistoric cephalopod offers a glimpse into predator-prey interactions from 150 million years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/ff/fcff737d-9fce-4c8f-9bfd-59a54ac4777b/120519_jp_pterosaur-squid_feat-1028x579.jpg)

For one unfortunate pterosaur looking for lunch 150 million years ago, calamari was a risky choice.

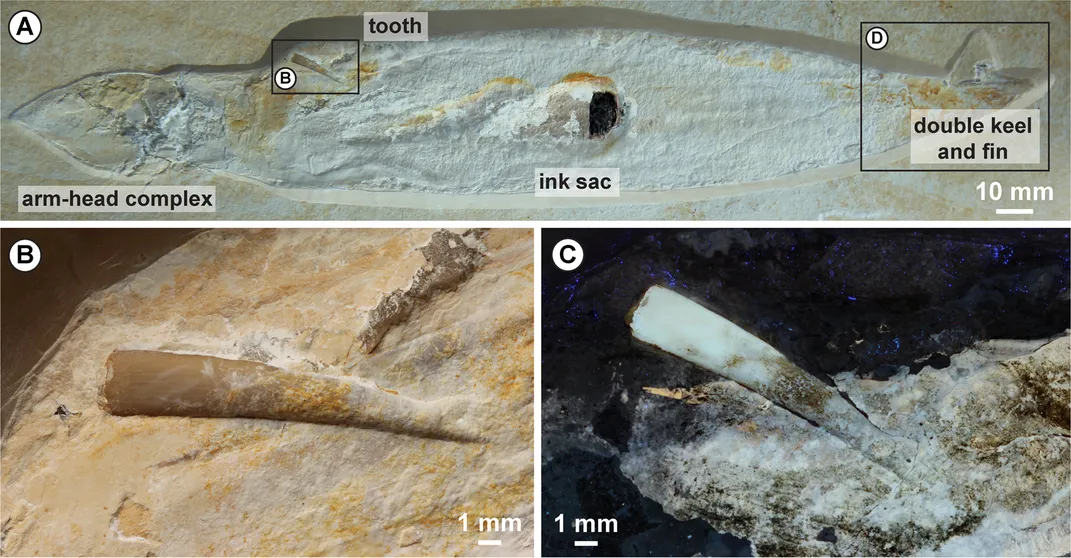

A new cephalopod fossil, described last week in the journal Scientific Reports, was unearthed with a surprising accessory: an embedded tooth, almost certainly torn from the mouth of a flying reptile that tried—and failed—to grab a quick bite from the sea.

The fossilized meal-gone-awry represents the first known evidence that pterosaurs hunted cephalopods, perhaps to varying degrees of success, Jean-Paul Billon Bruyat, an expert in prehistoric reptiles who was not involved in the research, tells Cara Giaimo at the New York Times.

Excavated in 2012 from a limestone formation in Bavaria, Germany, the specimen was photographed before disappearing into the collections at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. But last year, René Hoffmann, a paleontologist at Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany, stumbled across the image, depicting what appeared to be a Plesioteuthis subovata cephalopod, a predecessor of today’s squids, octopuses and cuttlefish. The 11-inch-long creature, Hoffmann notes in an interview with the New York Times, was extremely well preserved, with its ink sac and fins still partially intact. But what struck him the most was the sharp-looking tooth protruding from just below the animal’s head.

Based on the size, shape and texture of the dentition, as well as its approximate age, Hoffmann and his colleagues argue that it probably belonged to a Rhamphorhynchus muensteri pterosaur with a hankering for seafood, reports John Pickrell for Science News.

Perhaps, after coming across a group of surface-skimming cephalopods, the winged reptile dove in for a taste, sinking at least one tooth about half an inch deep into squiddy flesh. But due to either the size or heft of the prey, or poor positioning on the pterosaur’s part, the pair’s rendezvous was brief—and the cephalopod managed to wrest itself free, taking with it a toothy souvenir. (Though this liberation may have represented something of a pyrrhic victory, and the prehistoric squid then died of its injuries before fossilizing on the silty ocean floor.)

Though drawing conclusions about ancient animal encounters can be difficult, Hoffmann and his colleagues support the idea that the detached tooth was the product of violence. However, Jingmai O’Connor, a paleontologist at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, advises caution in interpreting the fossil, suggesting at least one other way the ancient cephalopod’s body might have snared the tooth: “Perhaps the squid fell to the bottom of the sea when it died and landed on a pterosaur tooth,” she tells the New York Times.

This more passive fossilization scenario is probably unlikely, as the tooth isn't just resting on the fossil but instead seems to have been “jammed in [the cephalopod] and broken off,” explains Riley Black for Scientific American.

We may never know the true nature of the tooth’s demise with certainty. But if the mixed-species fossil does indeed immortalize a rare pterosaur-prey interaction, it should be considered rare and unique, Taíssa Rodrigues, a pterosaur researcher at the Federal University of Espírito Santo in Brazil, who was not involved in the study, tells Science News. “In the few cases we do have, pterosaurs were the prey of large fish,” she says. “So it is great to see this the other way around.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)