A Penguin Colony’s Rise and Fall, Recorded in Poop

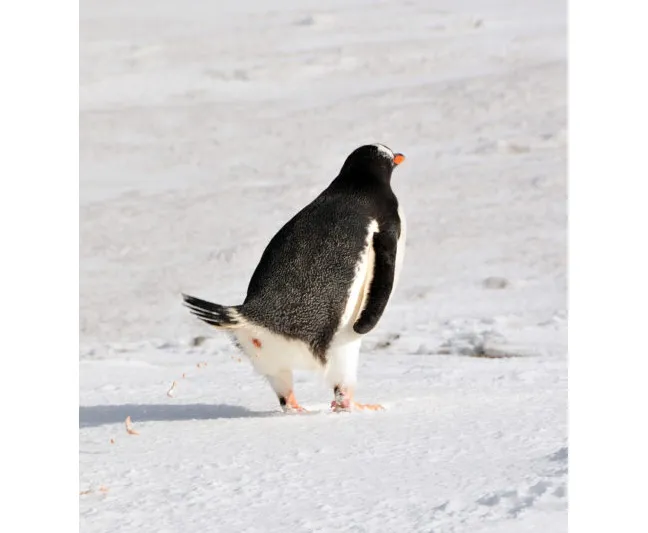

A nearby volcano has decimated the gentoo colony on Ardley Island three times

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/47/de47f8d6-06b0-4926-812d-eea2a0addbc2/image-27.jpeg)

The gentoo penguin colony at Ardley Island have called this little piece of Antarctica home for nearly 7,000 years. Today, some 5,000 breeding pairs raise their chicks there each year. But as James Gorman reports for The New York Times, there is one problem with the location—every so often a volcano on nearby Deception Island blows its top, completely destroying the penguin colony.

An international team of researchers recently mapped the history of the penguin colony by taking a look at their of guano—or bird poop. Generation after generation, the creatures deposit this history in layers all over the island. So the researchers collected sediment cores from one of the island's lakes, and used the layers of guano that washed into the lake to estimate the size of the penguin population. While they expected to find only minor fluctuations in the population, the guano showed something very different.

“On at least three occasions during the past 7,000 years, the penguin population was similar in magnitude to today, but was almost completely wiped out locally after each of three large volcanic eruptions,” says Steve Roberts from the British Antarctic Survey. “It took, on average, between 400 and 800 years for it to re-establish itself sustainably.” The researchers published their work in the journal Nature Communications.

As Gorman reports, the researchers did not initially set out to study the guano cores. Instead, they were interested in studying changes in climate and sea level. But when they brought up the one 11.5-foot section they noticed it had a distinctive smell, and they could see the layers of guano and ash.

"[It] had some unusual and interesting changes in geochemistry that were different from those we had seen in other lake sediment cores from the area," Roberts, who was lead author of the study, tells Laura Geggel at Live Science. "We also found several penguin bones in the Ardley Lake core."

This led them to study the geochemical make-up of the sediment, which they used to estimate the penguin population over time. The poop suggests that the population has peaked five times over nearly 7,000 years. And while volcanic eruptions decimated the colony three times (5,300, 4,300 and 3,000 years ago) it’s not clear what caused the population to fall after the other two peaks, Helen Thompson reports for ScienceNews. The condition of sea ice and atmospheric and ocean temperatures did not seem to impact the size of the colony.

The major takeaway is that penguins and volcanoes don’t mix. “This study reveals the severe impact volcanic eruptions can have on penguins, and just how difficult it can be for a colony to fully recover,” Claire Waluda, a penguin ecologist from the British Antarctic Survey says in the press release. “An eruption can bury penguin chicks in abrasive and toxic ash, and whilst the adults can swim away, the chicks may be too young to survive in the freezing waters. Suitable nesting sites can also be buried, and may remain uninhabitable for hundreds of years."

Penguins and volcanoes encounter each other more than you might think. Last year a colony of 1 million chinstrap penguins on Zavodovski Island in the South Sandwich Islands just off the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula became threatened when the nearby Mount Curry Volcano began erupting. As Gorman reports, the last time Mount Deception erupted was in 1970, but it was nowhere near the magnitude of the eruptions that wiped out the gentoos.