This Gallery Is Dedicated to Coal Miners’ Art

The Mining Art Gallery showcases works created by the thousands of miners who’ve lived and worked in the Great Northern Coalfield

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/f0/42f08de8-f607-4be5-977d-a7b232f3b12d/take_five.jpg)

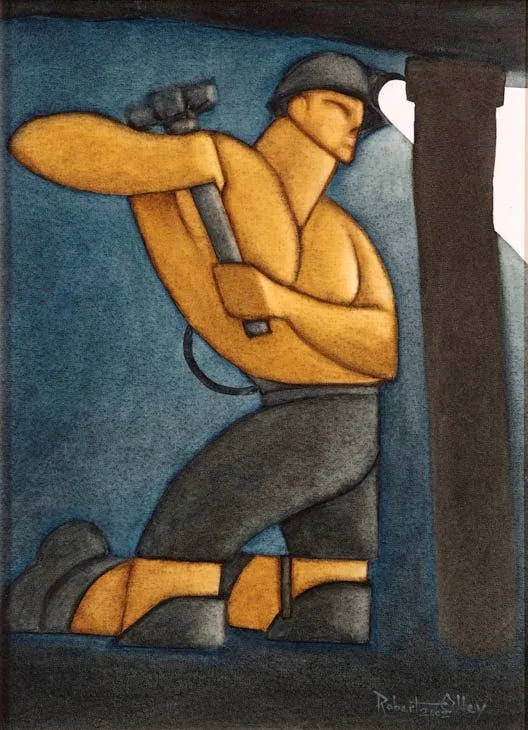

In the 1930s, coal miners based out of Ashington, Northumberland, began an art appreciation class out of their local YMCA. The Ashington Group, as they called themselves, stuck to the philosophy "paint what you know," and the group became a sensation, capturing a unique look at life in coal mines and coal towns. The life and times of the miners, dubbed the "Pitmen Painters" have been chronicled by art critic William Feaver and also adapted into a Broadway play. Now, reports Javier Pres at artnet News, their work and more are featured in the first museum gallery dedicated to the coal art genre in the United Kingdom.

The Mining Art Gallery at Auckland Castle opened its door on October 21, four years after millionaire investment banker and art collector Jonathan Ruffer bought an abandoned castle in Bishop Auckland in County Durham with plans to develop the economically challenged area into a cultural destination. While Ruffer eventually hopes to create a museum of faith, historical theme park and display his true love—the work of Spanish Old Masters—he opened the Mining Art Gallery first as a tribute to the industry that dominated the area for generations and closed for good in the 1980s. “Spanish art might not appeal directly to local people,” Angela Thomas, assistant curator of the museum, tells Pres. “The Mining Art Gallery is a way of saying, ‘This is your heritage.’”

One of the artists featured in the museum is 77-year-old Bob Olley, who worked underground for 11 years. He tells the BBC that art is a way for miners to show the world what life was like underground and what day-to-day existence involved for families and towns that powered the industrial age. “In days gone by, before cameras and mobile phones, you couldn't show people, ‘that’s what I do at work,” Olley says. “I think that may be part of why there's so many people who came out of coal mining being artists. We are lucky because we have had the exposure, but there must have been thousands of other people in the industry that didn't, and nobody has seen their work.”

Maev Kennedy at The Guardian reports that local officials tried to have Olley’s most-famous image, the Westoe Netty—a cheeky depiction of six men and one youth at a netty (slang for lavatory)—banned when it was first shown. They were unsucessful, and the Westoe Netty has become a symbol of North East working-class history (a print of the work is also featured at the Mining Art Gallery).

The heart of the 420-piece collection comes from two local collectors, librarian Gillian Wales who discovered the art and began collecting when a local miner-artist hung a flyer in her library advertising his art show in London. She shared her discovery with local physician Bob McManners and the two began collecting the work of local artists, including Norman Cornish, Tom McGuinness and Polish-Jewish émigré artist Josef Herman whose work is held by major museums. According to a press release, they put together a history of the art highlighting the work of the Spennymoor Settlement painting group based a few miles outside Bishop Auckland as well as the Ashington Group and individual painters across the Great Northern Coal Field.

The museum hopes that once the public sees the work on display, they will come forward with more miner art that they may unwittingly have stored away in their attics and garages.

As memory of the “pit towns” fades, Olley tells Kennedy that conserving this art is increasingly important. “It won’t take long until all we have left is the paintings,” he says.