Why Did Restorers Search a Civil War Battleship’s Guns for the Remains of a Black Cat?

Clearing out the eight-ton, 11-foot-long cannons gave conservators a chance to follow up on the tale of an unlucky feline

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a2/ea/a2ea7fc9-a0e9-4a14-af8d-14e40cdc73e5/boat3.jpg)

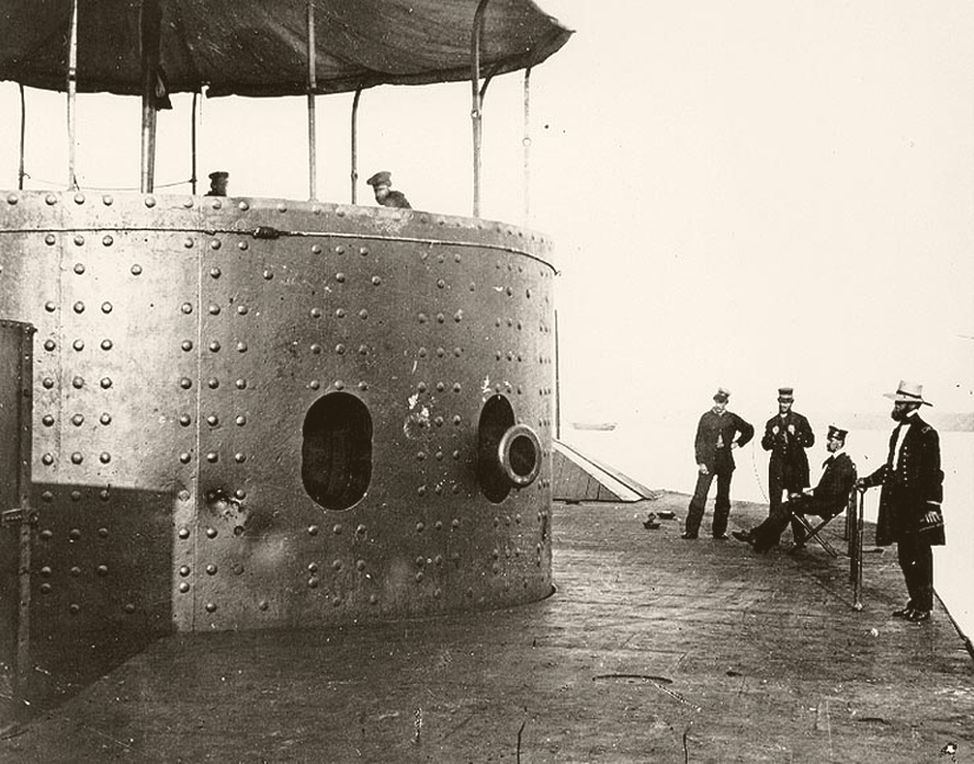

Naval warfare changed on March 9, 1862, when two ironclad battleships clashed for the very first time. Meeting at the mouth of Virginia’s James River in the midst of the American Civil War, the Confederate CSS Virginia—an ironclad built by reinforcing the remains the Merrimack, a Virginia frigate the Union had tried to destroy when the state announced its secession—vied with the Union’s USS Monitor, an ironclad equipped with a revolutionary mobile gun turret. While other ships had to maneuver the entire hull in order to aim their guns, the Monitor could spin its two cannons and aim with relative ease.

The Monitor is the “mother of all battleships,” says Erik Farrell, archaeological conservator at the Mariners’ Museum and Park in Newport News, Virginia, to Michael E. Ruane of the Washington Post. Last week, Farrell and his colleagues undertook a major step in restoring the Monitor’s cannons for display, boring out the 11-foot-long barrels with a custom-built drill and releasing more than 100 years of marine muck.

“They’re the largest smoothbore guns ever recovered from an archaeological site,” Farrell tells the Washington Post.

Though the Monitor escaped its battle with the Virginia intact, it crossed paths with a hurricane just nine months later and sank the off the coast of North Carolina.

One of the ironclad’s sailors, a Rhode Islander named Francis Butts, survived the wreck and, several years after the end of the Civil War, wrote an account of the ship’s sinking. While bailing water in the Monitor’s famed turret, he recounted, Butts plugged one gun with his coat and boots. Then, he saw “a black cat … sitting on the breech of one of the guns howling.”

“… I caught her,” wrote the sailor, “and, placing her in another gun, replaced the wad and tompion, but I could still hear that distressing howl.”

Butts never explained why he decided to plug the cat in the cannon. (“Was he trying to save it?” asks the Post. “Or quiet its wailing?”) Still, archaeologists kept the legend in mind as they began to recover artifacts from the Monitor.

A research team located the shipwreck, which is now managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and its Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, during the early 1970s. NOAA and the U.S. Navy collaborated to recover the gun turret in 2002. Two years later, researchers removed the cannons from the turret. But 140 years in saltwater had taken a toll on the metal.

As Will Hoffman, the museum’s director of conservation, tells the Daily Press’ Josh Reyes, the cannons are as soft as chalk in some places. To preserve the guns, the museum stores them in a chemical solution that draws out salt and protects against sudden oxidation.

“The goal of this is to really get the artifact on display so it can tell the story of the Monitor, the leadup to the battle between ironclad ships, the aftermath,” Hoffman tells Christopher Collette of 13 News Now. “Because just nearby is the turret of Monitor, which the gun was found inside. That’s the first turret on a ship in human history.”

The Daily Press reports that David Alberg, superintendent of the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary, hopes the cannons will be ready for display within two or three years; 13 News Now, however, cites an estimate suggesting conservation efforts may take closer to ten years.

The Monitor’s turret sank upside down, filling the cannons with coal intended for the engine. So, when conservators bore through the cannon barrels last week, the majority of materials recovered were black water and chunks of coal-colored marine concretions. A preliminary search of the cannon barrels in 2005 showed no sign of cat remains, and last week’s boring yielded a similar result. The only artifact of interest recovered was a single metal bolt.

Laurie King, an assistant conservator at the museum, tells the Post that she loves the cat story regardless of its veracity.

“Even if it turns out to not be true, I really like Butts, and the fact that he had such an imagination, and felt like, ‘Oh no one’s going to know the difference,’” says King. “I don’t think he ever would have imagined that we could bring it up a hundred and fifty years later. It’s … wonderful to be able to do this archaeology to confirm or deny stories and oral histories that have been passed down over generations.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/86/be/86be6548-1a05-4093-8190-15b45813f8b7/boat1.jpg)