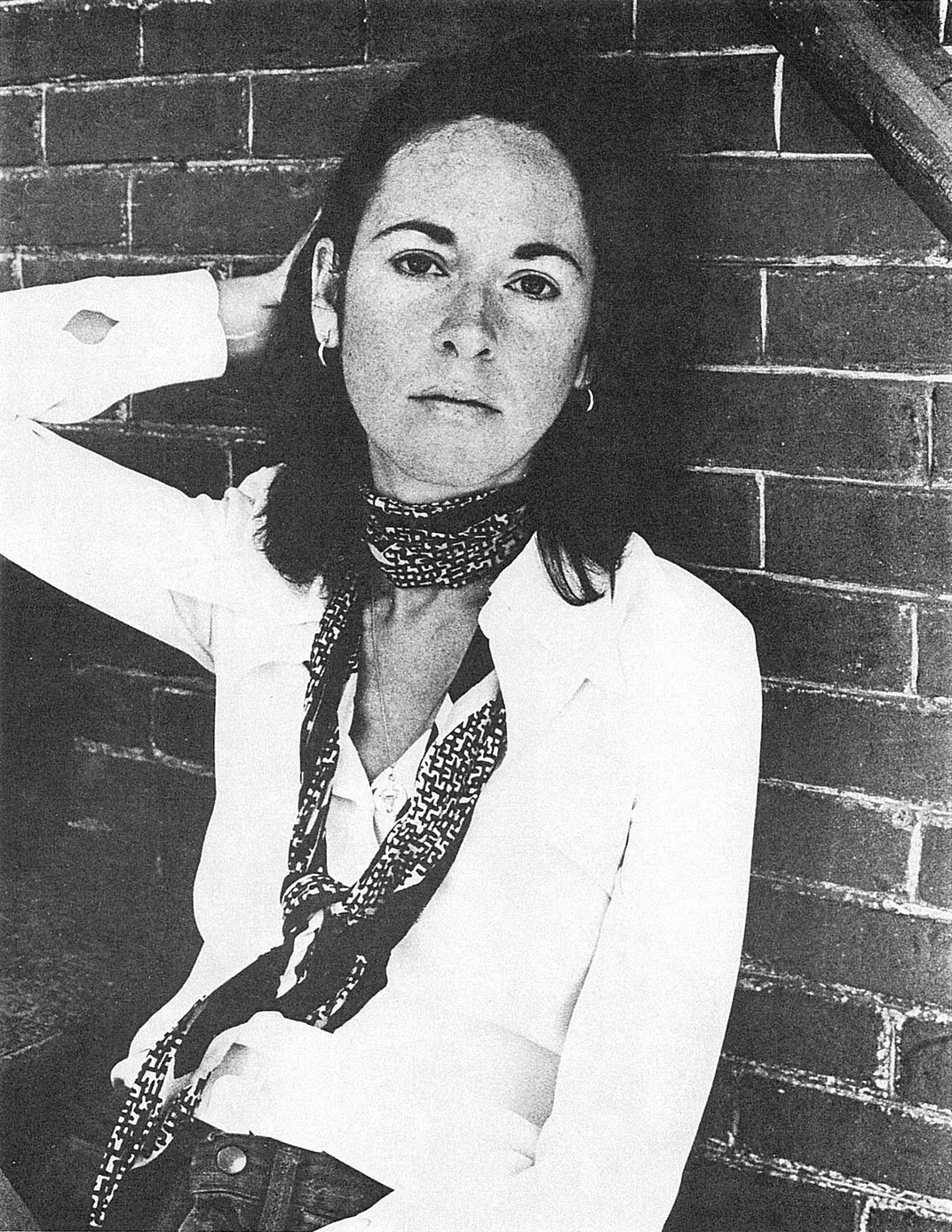

American Poet Louise Glück Wins Nobel Prize in Literature

The esteemed writer and teacher previously won the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/16/4e169a4a-fab9-4911-9a21-ab57ed58fa07/gluck_copy.jpg)

Louise Glück, an American poet whose work discusses such topics as trauma, families, beauty and death, has won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature. Announcing the win Thursday, the prize committee cited Glück’s “unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

In recent years, the literary prize—once considered the most prestigious in the world—has been mired in controversy. The Swedish Academy, which is responsible for choosing winners, delayed the announcement of its 2018 honoree, Olga Tokarczuk, by a full year after an academy member’s husband, Jean-Claude Arnault, was accused of sexual assault and leaking prize winners to bookies. The scandal was cited by some as an example of the academy’s broader culture of sexual harassment and corruption; in a statement announcing the postponement, the Swedish organization acknowledged that it would need time to recover public confidence. Arnault was later convicted of rape and sentenced to two years in prison.

Last year, the committee’s decision to award the Nobel to Austrian author Peter Handke also raised eyebrows. Per the Guardian, Handke has previously expressed support for the late Serbian dictator and war criminal Slobodan Milošević, in addition to publicly denying the 1995 Srebrenica genocide, in which Bosnian Serb forces murdered at least 8,000 Muslim men and boys. Interestingly, the announcement came in the same month that Anders Olsson, chair of the prize-giving committee, emphasized the judges’ desire to move away from the award’s “Eurocentric,” “male-oriented” history.

All told, many experts expected the academy to “play it safe in the wake of three years of controversy,” writes Alison Flood for the Guardian. Antiguan-American novelist Jamaica Kincaid, Canadian poet Anne Carson and Guadeloupean novelist Maryse Condé were among the less divisive figures widely thought to be in contention.

Ahead of this morning’s announcement, however, Rebecka Karde, a journalist and member of the committee that selected Glück, told the New York Times’ Alexandra Alter and Alex Marshall that “[w]e haven’t focused on making a ‘safe’ pick or discussed the choice in such terms.”

She added, “It’s all about the quality of the output of the writer who gets it.”

Glück has published 12 collections of poetry, including The Wild Iris, which garnered her the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. She served as the United States Poet Laureate from 2003 to 2004 and received the National Humanities Medal in 2016.

Born in New York City in 1943, Glück struggled with anorexia nervosa as a teenager and young adult. In later writings, she cited her seven years of psychoanalytic therapy as key to her development as a writer.

“Analysis taught me to think,” the author reflected in 1995.

Per the Poetry Foundation, Glück’s work often draws on Greek and Roman mythology, regularly returning to themes of existential despair and agony.

One of Glück’s most anthologized poems is “Mock Orange,” which connects the scent of a flowering shrub to sex and despair: “How can I rest? / How can I be content / when there is still / that odor in the world?”

“Louise Glück’s voice is unmistakable,” said Olsson at the Nobel announcement, per the Times. “It is candid and uncompromising, and it signals this poet wants to be understood.”

The writer published her first book of poetry, Firstborn, in 1968. She numbers the among just a handful of Americans poets who have won the award, and is only the 16th woman to win in the prize’s 119-year history, according to Hillel Italie of the Associated Press.

In a statement cited by the AP, Peter Salovey—president of Yale University, where Glück currently works—describes the Nobel Laureate as a “galvanizing teacher.” Before arriving at Yale, she taught at Williams College and Boston University, among other institutions, mentoring notable poets including Claudia Rankine.

Glück had previously expressed skepticism about awards in a 2012 interview with the Academy of Achievement.

“Worldly honor makes existence in the world easier. It puts you in a position to have a good job. It means you can charge large fees to get on an airplane and perform,” she said, as quoted by the AP. “But as an emblem of what I want—it is not capable of being had in my lifetime. I want to live after I die, in that ancient way. And there’s no way of knowing whether that will happen, and there will be no knowing, no matter how many blue ribbons have been plastered to my corpse.”

"It's too new … it's too early here."

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 8, 2020

Take a listen to this brief conversation with new Literature Laureate Louise Glück, recorded shortly after the announcement of her #NobelPrize: pic.twitter.com/g6qg4lf84r

Now 77, Glück, who lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, typically shuns publicity. She will deliver her Nobel lecture in the United States due to travel and safety restrictions associated with the Covid-19 pandemic, reports the Times.

Nobel Prize Media interviewer Adam Smith called Glück early Thursday morning to share his congratulations. During their brief conversation, Glück demonstrated a dry wit characteristic of her written work.

“For those who are unfamiliar with your work—” began Smith.

“Many,” she quipped.

“—would you recommend a place to start?” he continued.

Glück went on to recommend her poetry collection Averno (2006) or her most recent work, Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014), which won the National Book Award for Poetry. She noted that it was “too early” to answer questions at length, and that the prize was “too new” for her to fully explain what it meant. Practically speaking, she said, she plans on using the prize money—10 million Swedish krona, or about $1.12 million, per NPR—to buy a house in Vermont.

The poet added, “But mostly I am concerned for the preservation of daily life, with people I love.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)