Stories of Forgotten Suffragettes Come Alive in New Exhibition

The Museum of London’s “Votes for Women” show marks 100 years since women were first granted the right to vote in Britain

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/0c/2a0c3b0b-a675-40f2-9e25-c479cab30cbd/women_stand_in_gutter_for_a_poster_parade_organised_by_the_womens_freedom_league_to_promote_the_suffrage_message_c_museum_of_london.jpg)

When the famed suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst appeared in public to campaign for women’s right to vote, she was flanked by an army of club-wielding female bodyguards.

Among their ranks was Kitty Marshall, who, like other members of Pankhurst’s entourage, was trained in jujitsu so she would be able to fight off detractors who came to hassle, heckle or manhandle the suffragettes’ magnetic leader.

Throughout her time as an activist, Marshall was actually sent to prison six times—the first after hurling a potato through the window of Winston Churchill’s residence. But while Pankhurst remains an iconic figure associated with the suffragette movement, Marshall has been largely forgotten. Now, her contributions to the fight for equal rights are being highlighted at the Museum of London, in an exhibition marking the centenary of Britain’s 1918 Representation of the People Act.

The legislation, signed by parliament on February 6, granted the right to vote to women over the age of 30 who met certain property requirements—a vital step toward universal suffrage. The milestone is being celebrated across the U.K. this year with a range of events and programming, but the Museum of London is particularly well-positioned to commemorate the centenary. The institution is home to the world’s largest collection of material relating to the suffragettes, who distinguished themselves from the suffragists by their willingness to resort to militant action.

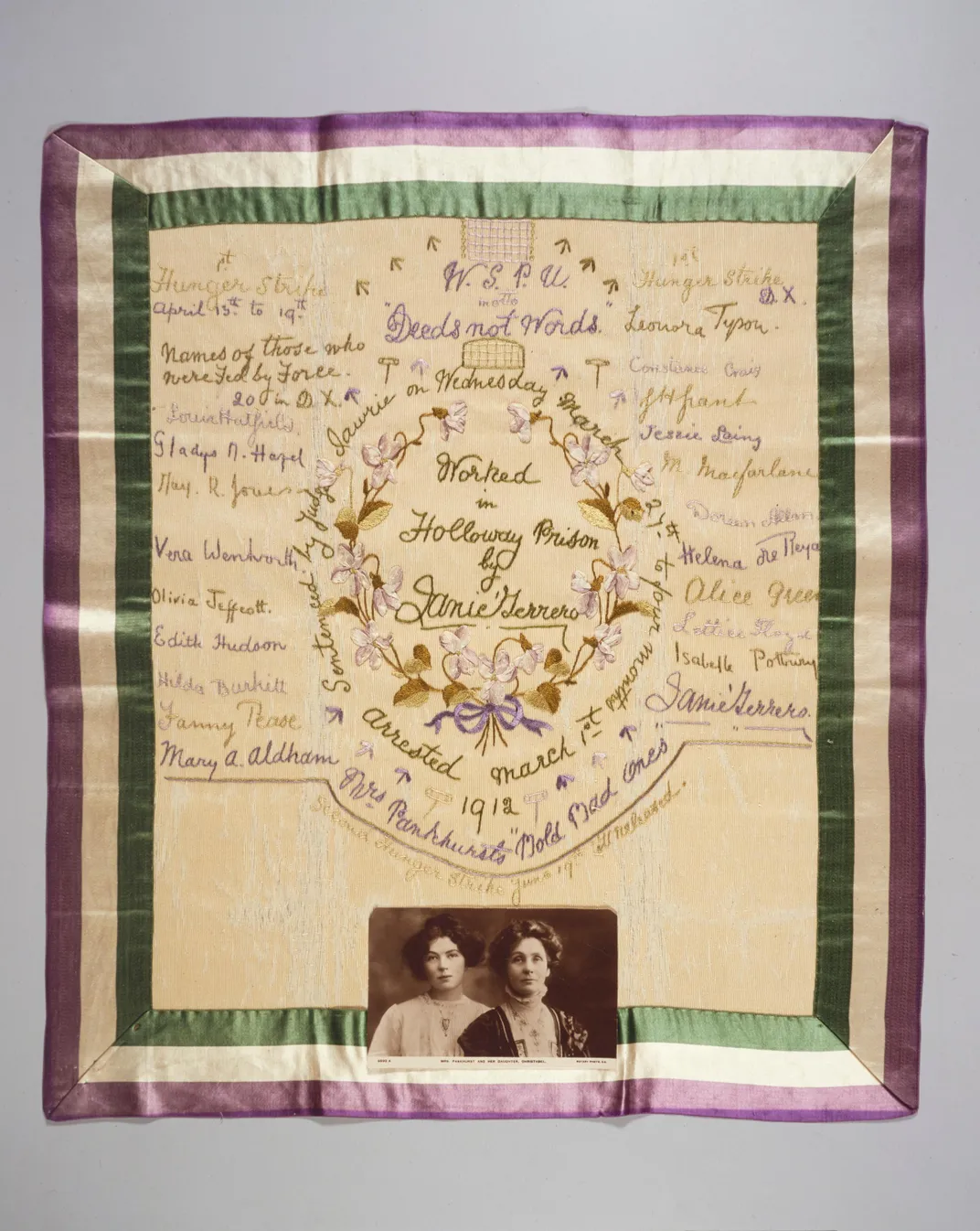

Titled “Votes for Women,” the show explores the untold stories of the lesser-known members of the movement. Curator Beverley Cook tells Smithsonian.com that she was “very keen” to focus on these women who campaigned for enfranchisement at great personal cost. Exasperated by the repeated denial of their rights, activists like Kitty Marshall smashed windows, set fires and vandalized artworks. They were sent to prison, where they went on hunger strikes and endured torturous forced feedings.

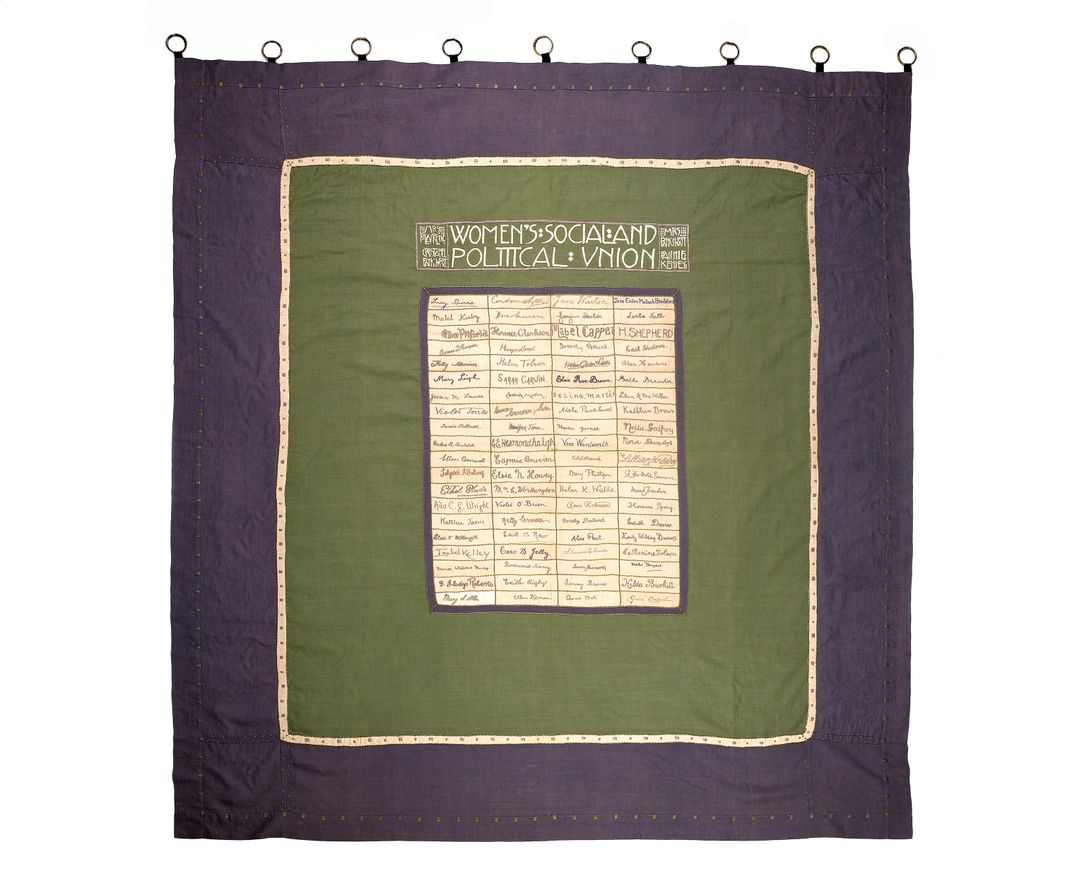

Among the items on display at “Votes for Women” are gifts that honored the suffragettes’ sacrifice and paid tribute to their suffering. Visitors can, for example, view a silver medallion necklace that was presented to Marshall, which is inscribed with the dates of her prison sentences. Also on display is a gift given to Louise Eates, who established a local chapter of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), an activist organization founded by Pankhurst. Eates served one prison term for suffragette militancy and, upon her release, was presented with a beautiful pendant depicting an angel kneeling before a barred prison window.

“You find with a lot of suffragettes there's a quite spiritual element to the campaign,” Cook explains. “There’s also a very strong militaristic element.”

But in “Votes for Women,” the exhibition makes a point to show that the movement was fueled by much more than its adherents’ willingness to take up violent action. The suffragettes were highly organized, establishing chapters of the WSPU throughout the country and dispatching delegates to galvanize people to the cause.

“People are very engrossed in some of the militant action: the window smashing, the arson, the bombing,” Cook says. “But I wanted to reveal to the public that that was actually one side of the campaign. The campaign had behind it a really strong foundation. Many of the women were amazing organizers, but also inspirational speakers, and very successful at fundraising.”

Accordingly, one of the exhibition’s displays focuses on the women who ran the WSPU. Ada Flatman, for example, was a salaried employee of the organization who travelled across the nation to rouse supporters. “Votes for Women” features a scrapbook—stuffed with tickets and flyers—that she kept to chronicle her work in diverse regions, from industrial cities like Liverpool to the middle class town of Cheltenham.

By delving into the suffragette’s biographies, the exhibition also reveals just how different they were. Some campaigners, like Pankhurst, came from politically active and well-off families. Others did not. Flatman, for instance, only became interested in the suffragette movement after travelling to Australia (“quite an adventurous thing to do at the time,” says Cook) and speaking to women there, who had already been granted the vote.

Kitty Marion, a German immigrant who worked as an actress in rowdy music halls, was barely scraping together a living when she joined the cause. She had grown frustrated with the “casting couch mentality” of the acting business, Cook explains, and was also shocked by the number of young girls she had seen forced into prostitution. As an activist, she sold the suffragette newspaper, joined the Actresses’ Franchise League, and one even burned down a racecourse in protest. “Votes for Women” includes a page from one of her scrapbooks, where Marion proudly pasted newspaper clippings that reported on such militant acts.

While the suffragettes hailed from disparate backgrounds, they were united by their determination and bravery. Cook stresses that these activists, while brazen and iron-willed, were extremely vulnerable. They marched into major streets, often on their own, to hand out newspapers and flyers. Because they could be arrested for obstruction if they stood on the pavement, the suffragettes planted themselves in busy roadways and gutters.

“They were at the mercy of any passersby,” Cook says. “Suffragettes were satirized, they were heckled, they were shouted at. Anyone who put themselves forward to say, ‘I am a suffragette,’ was being very brave.”

One of the exhibition’s most striking illustrations of the campaigners’ resolve is arguably a 1910 photograph of a young suffragette named Charlotte Marsh. Dressed in pearly white, Marsh appears almost angelic in London’s Hyde Park, surrounded by a sea of male onlookers wearing dark suits. But on her dress, she bears a pin that identifies her as a former prisoner who endured grisly forced feedings. She is no frail creature. Rather, she is a warrior, holding her ground.

“I think that is one of the lasting legacies of the campaign: the self-confidence that you see in some of the women through our images, through our objects and through our writings,” Cooks says. “I wanted to represent [the suffragettes] as self-confident—as standing strong in a man's world.”