Lead Poisoning Wasn’t a Major Factor in the Mysterious Demise of the Franklin Expedition

Researchers argue that lead exposure occurred prior to the start of the voyage, not during the stranded crew’s battle for survival

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/4d/ae4ddc07-81ca-4218-b5f3-bbf2d4b71f07/3724751902_62240d45f3_b.jpg)

In September 1854, a Scottish explorer named John Rae published a harrowing account of the Franklin Expedition’s “melancholy and dreadful” end. His report, based largely on first-hand testimony from the local Netsilik Inuits, was corroborated by artifacts salvaged from the doomed mission. Despite this proof, Rae was roundly condemned by individuals ranging from Charles Dickens to the wife of expedition leader Sir John Franklin. One sentence in particular attracted the strongest ire: “From the mutilated state of many of the bodies,” Rae wrote, “it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last dread alternative”—in other words, cannibalism—“as a means of sustaining life.”

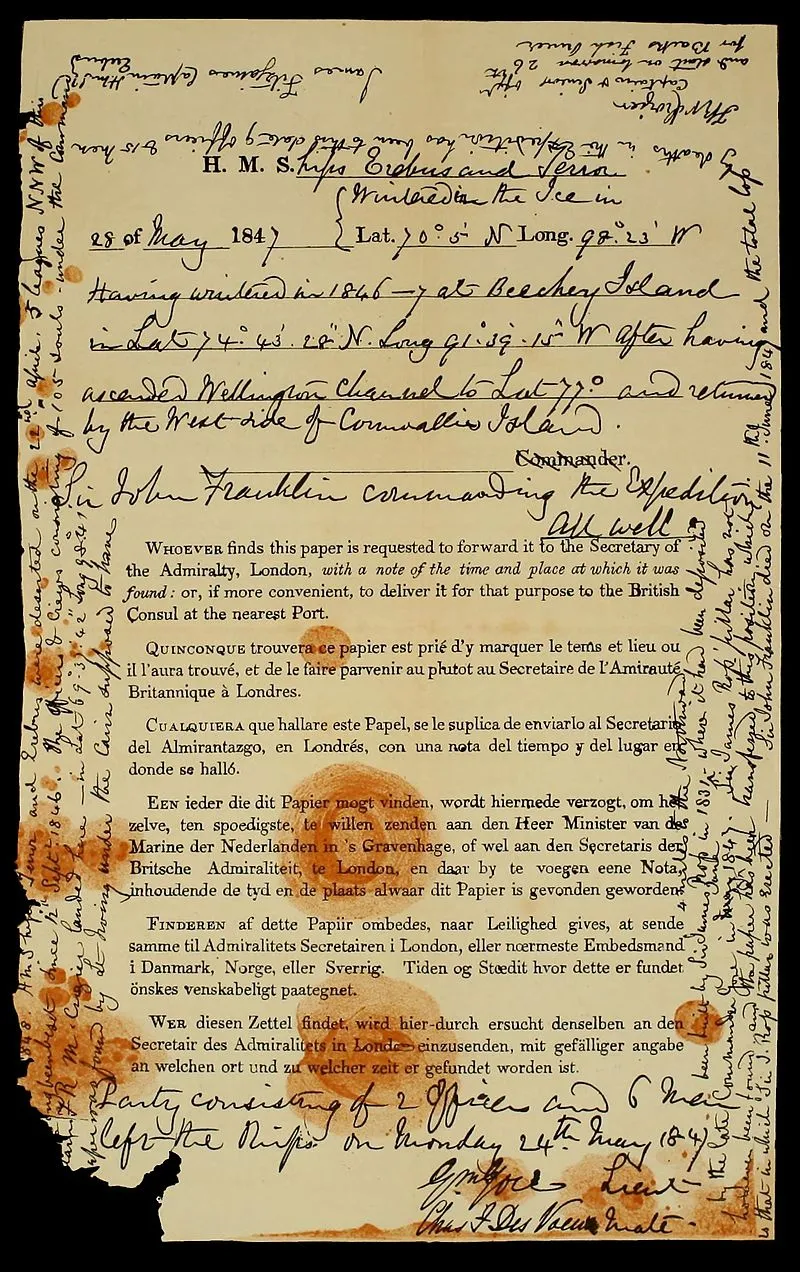

It had been six years since the HMS Terror and Erebus, as well as the ships’ 128 officers and crew, vanished while attempting to chart a northwest passage through the frigid waters of the Arctic. Rae’s account provided the first hints of Franklin’s fate, and an 1859 search team led by Francis Leopold McClintock unearthed an 1848 note detailing the crew’s increasingly dire straits. Over the years, further traces of the expedition, including burial sites and the resurrected remnants of both the Terror and Erebus, have emerged, but the circumstances surrounding the expedition’s demise remain an enduring mystery to this day.

Now, George Dvorsky reports for Gizmodo, a group of Canadian researchers has concluded that lead poisoning, one of the prevailing suspects behind the sailors’ deaths, was not a major factor in the expedition’s failure.

The team’s findings, newly detailed in Plos One, revolve around three hypotheses: First, if elevated lead exposure killed the crew, the bones of those who survived longest should exhibit a more extensive distribution of lead. Using the same logic, microstructural bone features formed around the time of death should show elevated lead levels, especially compared with older body tissue. Finally, the sailors’ bones should exhibit higher or more sustained levels of lead than those of a British naval population based in Antigua around the same time period.

Scientists used a high-resolution scanning technique known as confocal X-ray fluorescence imaging to assess the crew members’ bones. Although the team found evidence of lead, David Cooper, Canada Research chair in synchroton bone imaging, tells CBC Radio’s Saskatoon Morning that the dangerous element was “distributed extensively through their bones,” suggesting exposure occurred prior to the expedition. Given the prevalence of lead poisoning following the Industrial Revolution (as societies industrialized, they began incorporating lead into everything from paint pigments to gasoline and tinned cans of food), this explanation is unsurprising.

What’s more remarkable, Cooper argues, is the Franklin sailors’ endurance: “It's not a stretch of the imagination to understand how people die after two or three years in the Arctic,” he tells CBC. “This was a desperate situation, food supplies are running low, and there is evidence of cannibalism later on in the expedition. I think what's remarkable is that they survived as long as they did."

According to Mental Floss’ Kat Long, the Franklin Expedition departed England on May 19, 1845. Terror and Erebus held an astonishing 32,224 pounds of salted beef, 36,487 pounds of ship’s biscuit, 3,684 gallons of concentrated spirits and 4,980 gallons of ale and porter—enough to sustain the ships’ crew for three years.

Unfortunately, these exorbitant provisions prevented expedition leader Sir John Franklin’s wife, Jane, from convincing the British Admiralty to search for her husband and his crew after they failed to make contact with those back at home.

“The Admiralty kept saying, ‘They have enough food for three years. So we don’t need to worry until at least 1848,’” Paul Watson, author of Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition, tells National Geographic’s Simon Worrall.

During the winter of 1845, Franklin and his crew rested on Beechey Island, a small patch of land in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Three sailors died and were buried in the island’s permafrost, but conditions eased enough for the expedition to continue onward. On September 12, 1846, however, the Terror and Erebus found themselves entrapped in rapidly freezing waters. This time, there would be no burgeoning spring and summer winds to rescue the ships from their icy prison.

By spring 1848, the weather had still not relented. Only 105 men remained, as dozens of crew members, including Franklin, succumbed to unknown forces. Captain Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier, the expedition’s second-in-command, left a note detailing the men’s plight in a pile of stones on the northwestern coast of King William Island. The surviving sailors ventured inland, eventually encountering the Netsilik Inuit who would relay their unfortunate story to John Rae, but never made it to the trading posts where they hoped to find aid.

In 2014, archaeologists and Inuit historians discovered Erebus’ final resting place in the Victoria Strait. Two years later, search teams located the second ship, Terror, off of the southwestern coast of King William Island. These vessels, in conjunction with the array of bodies and miscellaneous artifacts salvaged over the centuries, provided evidence of the expedition’s gruesome end, but many aspects of the story are still unclear. Thanks to the new study, however, researchers are one step closer to finally reaching a definitive conclusion.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)