Kepler Finds 219 New Planets

NASA released the final catalog from its planet-hunting telescope, bringing its total up to 4,034 potential planets

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/58/015870ef-8c84-4a44-a633-9d138d892b0f/planets.jpg)

Yesterday, NASA released the final catalog from its Kepler Space Telescope planet-hunting mission, revealing 219 new exoplanets circling other stars, including ten Earth-sized rocky planets, orbiting in the so-called habitable zone, where it's plausible that liquid water—and perhaps life—could exist.

As Dennis Overbye at The New York Times reports, the catalog is the eighth and final data release from Kepler’s original four-year-mission between 2009 and 2013. To find all these new worlds, Kepler peered at an area of the sky near the constellation Cygnus, keeping an eye on more than 150,000 stars. The researchers analyze this data, watching for dips in brightness that can indicate a planet or planets passing in front of the star.

Kepler identified a whopping 4,034 potential planets. Of that lot, 2,335 have been confirmed as exoplanets and 50 lie in their star's habitable zone. The mission will officially end in September of this year, though the space telescope has continued on with a secondary mission called K2 in which it spends shorter periods looking for planets in other parts of space.

The latest catalog was created by taking a closer look at all four years of data from the Kepler mission. As NASA reports, the researchers inserted simulated planets into the data as well as false signals to test the accuracy of their analysis. They also used an algorithm called Robovetter to correct for noise in the data, Overbye reports, helping to bring the accuracy of the observations up to 90 percent.

Kepler’s catalogs of exoplanets will give researchers targets to look at as the next generation of space telescopes take to the skies in the coming years. “This carefully-measured catalog is the foundation for directly answering one of astronomy’s most compelling questions: how many planets like our Earth are in the galaxy?” Susan Thompson, research scientist for the SETI Institute says in the press release.

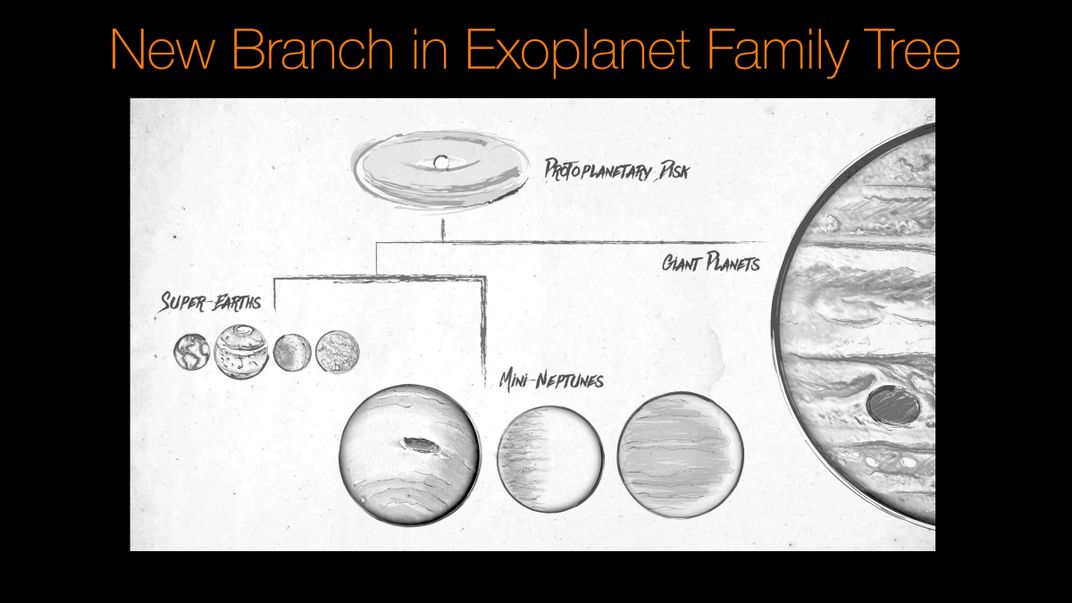

The Kepler data has also led to another interesting finding. Researchers at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii took a closer look at 1,300 stars examined by Kepler to measure the radii of the 2,000 planets orbiting them, Sarah Lewin writes for Space.com. They found two common types of planets: rocky super-Earths up to 1.75 times the size of our planet and “mini-Neptunes,” dense gas balls typically two to three and a half times the size of Earth.

Planets about 75 percent bigger than Earth are most common, according to the release. In about half those cases the planets take on extra hydrogen and helium, causing them swell into small gassy planets. “This is a major new division in the family tree of exoplanets, somewhat analogous to the discovery that mammals and lizards are separate branches on the tree of life,” Benjamin Fulton one of the authors said in a press briefing.

As Lewin reports, next year the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite will pick up where the Kepler mission left off, and the James Webb Space Telescope, also slated to launch next year, should be powerful enough to give us images of some exoplanets.

“It feels a bit like the end of an era, but actually I see it as a new beginning," Thompson said at the press briefing. “It’s amazing the things that Kepler has found. It has shown us these terrestrial worlds, and we still have all this work to do to really understand how common Earths are in the galaxy.”