This Hell-Raising Suffragist’s Name Will Soon Grace an Oregon Hotel

Abigail Scott Duniway staged a lifelong fight for women’s rights

If you’ve spent time in Portland, Oregon, you’ve probably walked past the Hilton Portland, a high-rise on SW 6th Avenue that was once the city’s tallest building. The hotel is currently undergoing a remodel and when it opens this spring, it will have another claim to fame—one related to women’s suffrage. Travel and Leisure’s Christopher Tkaczyk reports the hotel will be renamed The Duniway in honor of one of Oregon’s fiercest advocates for women’s rights.

Abigail Scott Duniway made her name as an outspoken supporter of equality for women, and also as a journalist during an era where a woman's byline was rare. Born in Illinois, she traveled the Oregon Trail with her family and lost her mother to cholera during a brutal, 2,400-mile wagon journey. Once she reached Oregon, she first taught school before getting married.

Duniway’s matrimonial life was plagued with financial and personal difficulties. Her husband lost his farm and when her husband suffered a debilitating accident, she became her family’s sole breadwinner. But though she shared these tragedies and worked hard to make ends meet, she had no legal rights. She began to buck against a life of perpetual service to her husband and children. “To be, in short, a general pioneer drudge, with never a penny of my own, was not pleasant business for an erstwhile school teacher,” she wrote.

Desperate for a steady income and driven by her growing sense of the injustice suffered by American women, she founded a pro-suffrage newspaper called The New Northwest in 1871. Its motto was “Free Speech, Free Press, Free People,” and Duniway took to its pages to call for women’s rights. She used her paper to help pull together like-minded women in the Pacific Northwest—and scored a major coup in that regard when she convinced Susan B. Anthony to visit Oregon. Duniway managed her lecture tour and used the momentum it built to organize a suffrage association for the state. She also voted illegally in the 1872 presidential election—like Anthony, who was arrested and prosecuted that year.

Tireless, outspoken and stubborn, Duniway was part of a tradition of western women’s rights advocates who won voting victories long before their sisters in the East. Western states like Wyoming, the first to grant women the vote, acknowledged the importance of women in pioneer society. But the reasons for these victories were complicated—Western states often gave women the vote to attract women from the East and even to bolster the voting power of conservative groups and the white majority. In addition, some Western feminists felt excluded from national efforts to gain women access to the ballot.

Over the course of her long career, Duniway wrote scores of novels and poems and founded other newspapers. But she never gave up her struggles on behalf of women, and refused to back down against anyone who was against the cause, unleashing the might of her pen in sarcastic and often hilarious tirades.

In one characteristic episode in 1872, she called Horace Greeley, the reformer and abolitionist who had recently refused to come out in support of women’s suffrage, “a coarse, bigoted, narrow-minded old dotard” and “an infinitesimal political pigmy.” (Historian Karlyn Kohrs Campbell also notes that when Greeley died not long after, Duniway eulogizes him with equally admiring words.) She even publicly feuded with her brother, also a newspaper editor, when he spoke out against her efforts.

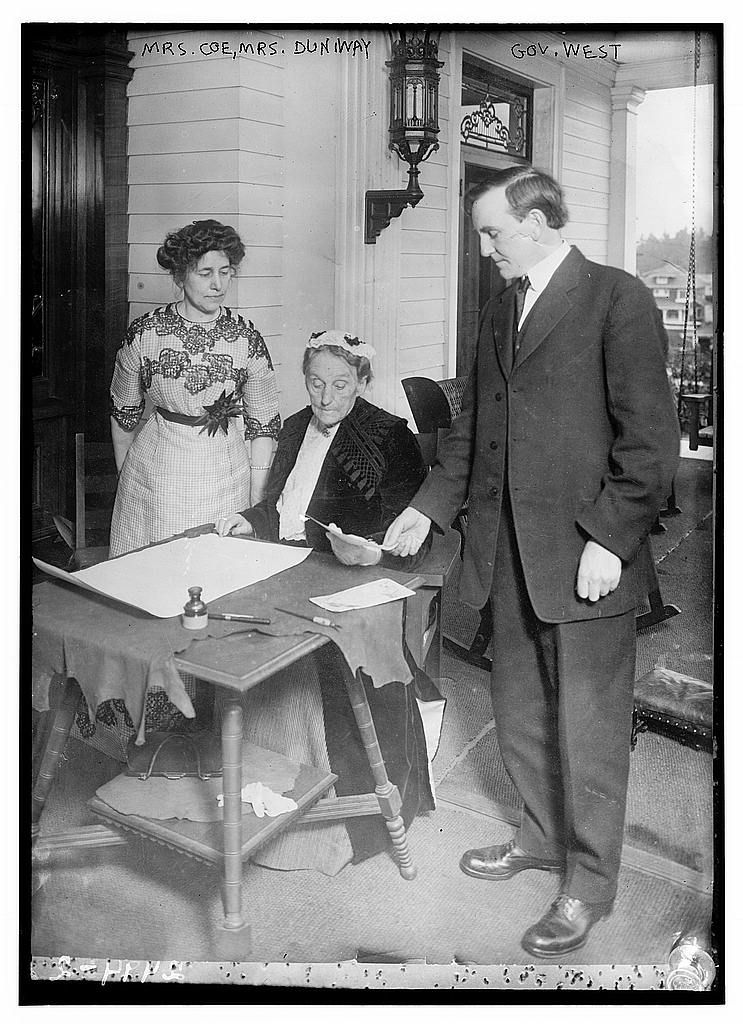

In 1912, she finally achieved a lifelong dream when Oregon men voted to give women the right to vote. When Oregon’s governor gave the Equal Suffrage Proclamation that made it law, she was asked to transcribe and sign it. But though she became the first woman to legally cast a ballot in Oregon, she died five years before the 19th Amendment was ratified.

Duniway may not have seen her most cherished wish come true, but her work set the stage for a whole new era of civil rights for women—rights the thoroughly modern journalist would have been all too happy to exercise during her own lifetime.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)