Newly Discovered Underground Rivers Could Be Potential Solution for Hawai’i’s Drought

The reservoirs could provide twice as much fresh water to tap into

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/27/01273a3f-42e2-4b00-8b3b-95da0d12f615/5014271797_fc1b5138ab_k.jpg)

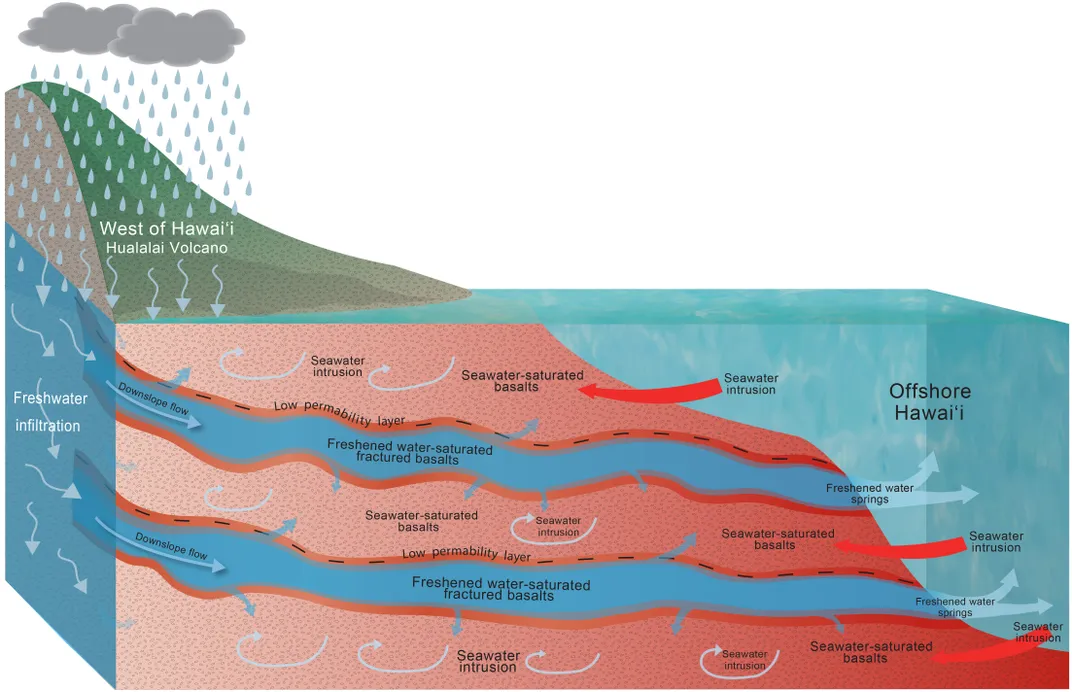

When rain pours down on the Hawaiian islands, water seeps through the topsoil, runs through porous volcanic rock and replenishes aquifers nestled deep underground. But over the last 30 years, rainfall on the islands has decreased by 18 percent. Meanwhile the number of residents has doubled since the late 1950s, leading to a high demand for an already scarce resource.

Even with the decrease in rainfall taken into consideration, the aquifers should hold more water than they do, which has puzzled scientists for years. Now, a team of researchers may have figured out where the missing fresh water goes, reports Michelle Starr for Science Alert.

In a study published last week in the journal Science Advances, a team of scientists discovered underground rivers on Hawaii's Big Island that transport fresh water from the island to the ocean. These rivers store more than twice the amount of freshwater than originally estimated, reports Matt Kaplan for the New York Times.

"Everyone assumed that this missing fresh water was seeping out at the coastline or traveling laterally along the island," lead author Eric Attias, a geophysicist at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, tells the Times. "But I had a hunch that the leak might be subsurface and offshore."

To figure out where the rest of the Big Island's fresh water was escaping from, a team of researchers used electromagnetic imaging to scan the island's coast, sort of like an underwater MRI. They hitched 131-foot-long antennae to a boat and towed it along the coast, scanning the submerged rock formations. Since saltwater conducts electricity much better than fresh water, the scans mapped out where fresh water flowed around the island, reports Krista Charles for New Scientist.

The scans revealed that the flows out from the island via underwater rivers hidden between layers of porous volcanic rock. The miles and miles of rivers contained more than 1.4 million Olympic swimming pools' worth of water—twice as much as originally predicted, reports Science Alert. In total, that's 920 billion gallons of freshwater, reports Sarah Wells for Inverse.

The team will need to drill into the rock and confirm the existence of the underground rivers. If the team is successful, this will be the first time the natural phenomenon has been documented, reports Inverse.

This discovery is a game changer for residents of the Big Island and for islanders across the globe. As climate change continues to intensify, droughts will too, further exacerbating the problem. It's possible other islands likely have a similar water process and that there could be even more fresh water to tap into, reports Timothy Hurley for the Star Advertiser.

"Given that Reunion, Cape Verde, Maui, the Galápagos and many other islands have similar geology, our finding could well mean that the water challenges faced by islanders all over the world might soon become a lot less challenging," Attias tells the Times.

Attias tells the Times that the water can be accessed using offshore pumps that bore into the aquifer and transport the water back to the mainland.

But other experts say that this plan must be executed cautiously. The entire island and its delicate ecosystem depend on the flow of fresh water, so they must be careful to not upset that natural balance.

"The fresh water that they have discovered is clearly being actively fed by the aquifer on the island," Graham Fogg, a hydrogeologist at the University of California, Davis, tells the Times. "This means that the entire aquifer system is connected, and our draining of this new water could adversely impact island ecosystems and water availability for pumps on the island."

Plus, tapping into that water source is easier said than done. A whole infrastructure would need to be built around it, including pumps, platforms and transmission lines, says Maui County planning director Michele McLean. But Attias says this would be an affordable and safe solution to Hawaiʻi's water problem.

"The water is already under high pressure, so little pumping would be needed, and, unlike an oil pump, there would not be any threat of pollution. If you have a spill, it’s just fresh water," he tells the Times.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rasha.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rasha.png)