Giant Salamander Goo Is Great at Gluing Gashes

Although slightly less durable than other surgical adhesives, a compound derived from the amphibian’s skin secretions performs better overall

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/02/9e02ff7a-7a79-40d6-acea-d4c84f69f3af/1024px-velemlok_cinsky_zoo_praha_1.jpg)

Sticky white mucus secreted by the world’s largest amphibian, the Chinese giant salamander, seals wounds more effectively than most medical glues used as alternatives to sutures and staples, a new study published in Advanced Functional Materials finds.

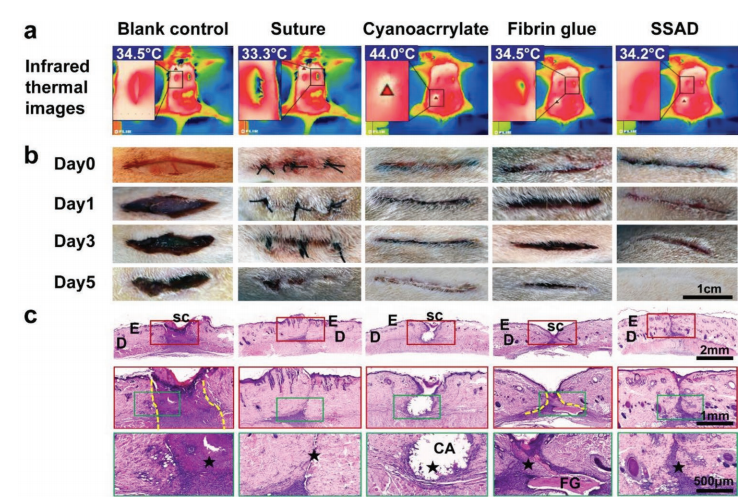

Laboratory testing showed that SSAD, a bioadhesive derived from the salamander’s skin secretions, easily closed wounds and promoted rapid healing in pigs and rats. Although slightly less durable than other medical adhesives, the compound performed better overall, offering strength, flexibility, and limited scarring and inflammation.

Compared with so-called “mechanical” approaches such as suturing and stapling, surgical glues lower patients’ risk of infection, lessen the potential for additional tissue damage and stress, and leave less scarring. But as George Dvorsky explains for Gizmodo, these synthetic adhesives—ideally “strong, sticky, bio-friendly, low cost, and easy to produce”—suffer from an array of limitations, including poor elasticity, cell toxicity and excessive heat applied at the site of the wound.

Additionally, the Daily Mail’s Alexandra Thompson writes, some individuals are allergic to or simply ill-suited for these alternative adhesives, which are known to slow down wound healing. Diabetics, for example, often have poor circulation linked with high levels of blood glucose, making it difficult for blood to circulate and properly repair injuries even without the presence of a decelerating agent.

SSAD, created by collecting goo from the salamander’s skin, freeze drying it, and adding a saline solution to form a gel-like glue, avoids these pitfalls. According to the study, the bioadhesive closed rats’ bleeding skin incisions in under 30 seconds, healed a “full-skin defect” in diabetic rats, and—most importantly for conservation concerns—thoroughly degraded inside of the body within three weeks of application.

“We anticipate that the low cost, environmentally friendly production, healing-promotion ability, and good biocompatibility of SSAD provide a promising and practical option for sutureless wound closure, as shown by the current research,” the researchers write in the study. “SSAD will likely overcome some limitations associated with currently available surgical glues and can perhaps be used to heal wounds on other delicate internal organs and tissues.”

Chinese giant salamanders, or Andrias davidianus, are called giants for a reason. As Gizmodo’s Dvorsky notes, the amphibians can grow to more than 5.9 feet in length and weigh upwards of 140 pounds. Popularly dubbed “living fossils,” the creatures have inhabited Earth for around 200 million years, making them roughly the same age as dinosaurs. One of the salamander’s most unusual characteristics is its mucus production, which occurs in response to scraping or other types of external stimulation. According to the study, Chinese people have used this goo to treat burns for some 1,600 years; research conducted in recent years further testifies to the salamander secretions’ healing abilities.

Crucially, study co-author Shrike Zhang of Harvard Medical School tells New Scientist’s Leah Crane, SSAD is essentially pure giant salamander goo.

But he adds, “I think if you happened to have a giant salamander by your side, putting the mucus right on should probably work too.”

Although the IUCN Red List classifies Chinese giant salamanders as critically endangered, Zhang explains that obtaining SSAD won’t harm the species, which is already regularly farmed for use in food and medicine.

“You don’t have to kill any animals,” Zhang concludes. “You just once in a while very gently scratch their skins to harvest the mucus. It’s very sustainable and you can obtain this adhesive for a long time.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)