Georgia Approves Changes to Stone Mountain Park, ‘Shrine to White Supremacy’

The site’s board authorized the creation of a truth-telling exhibit, a new logo and a relocated Confederate flag plaza

:focal(1697x668:1698x669)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/33/f133bb3d-601d-4b50-975f-3a3553998fee/gettyimages-1220495286.jpg)

Editor's Note, May 25, 2021: On Monday, the Stone Mountain Memorial Association board voted to implement a number of changes at the eponymous park, which is home to the world’s largest Confederate monument. As Tyler Estep reports for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, approved resolutions include creating an on-site exhibit that seeks to “tell the truth” about the park’s past, relocating a Confederate flag plaza to a less-trafficked area and designing a new logo. Stone Mountain Park’s controversial mountainside carving of Confederate leaders will remain intact.

“Some people are going to say [the changes are] not going far enough,” Bill Stephens, the chief executive of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association, which oversees the park, tells Timothy Pratt and Rick Rojas of the New York Times. “Others are going to say they’re going too far.”

Read more about Stone Mountain Park—and the nationwide push to remove Confederate monuments—below.

Stone Mountain—“the largest shrine to white supremacy in the history of the world,” in the words of activist Richard Rose—stands just 15 miles northeast of downtown Atlanta. Replete with Confederate imagery, including a monumental relief of Southern generals carved into the north face of a mountain, flags and other symbols, the state park has long courted controversy.

In the wake of a year marked by massive protests against racial injustice, officials are once again debating the contentious site’s future, reports Sudhin Thanawala for the Associated Press (AP).

On Monday, in a meeting with board members of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association (SMMA), CEO Bill Stephens proposed a number of “middle-ground” changes that stop short of removing the park’s infamous carved monument, per Tyler Estep of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC).

Among Stephens’ suggestions was the consolidation of Confederate symbols to a 40-acre area of the 3,400-acre park.

“So, if you want to see them you can come and you can see the Confederate monuments,” he said. “If you don’t want to see them and you want to go elsewhere in the park, then you can do that.”

As local news station WSB-TV reports, Stephens also proposed relocating the many Confederate flags that decorate the mountain’s trail, creating an educational exhibit about the Ku Klux Klan’s ties to the site, renaming the park’s Confederate Hall, incorporating acknowledgement of Native American burial grounds on park land and renaming a lake currently named for a Klansman.

Stephens argued that the park must change to remain financially viable but added that officials should not “cancel history,” according to the AP. (The park has lost a number of sponsorships and vendors in recent years due to its ties to white supremacy.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/10/e110c59d-cebc-4968-b41d-9bfc4e8734d4/stone_mountain_carving_2.jpeg)

Activists have been calling for transformational change at the park for decades. As the AJC notes, officials must work to balance these concerns with state laws that protect Confederate monuments.

The board did not immediately vote on any of the measures. But Abraham Mosley, a community advocate who was sworn in last week as the organization’s first-ever Black chairman, called the proposals a “good start,” per the AJC.

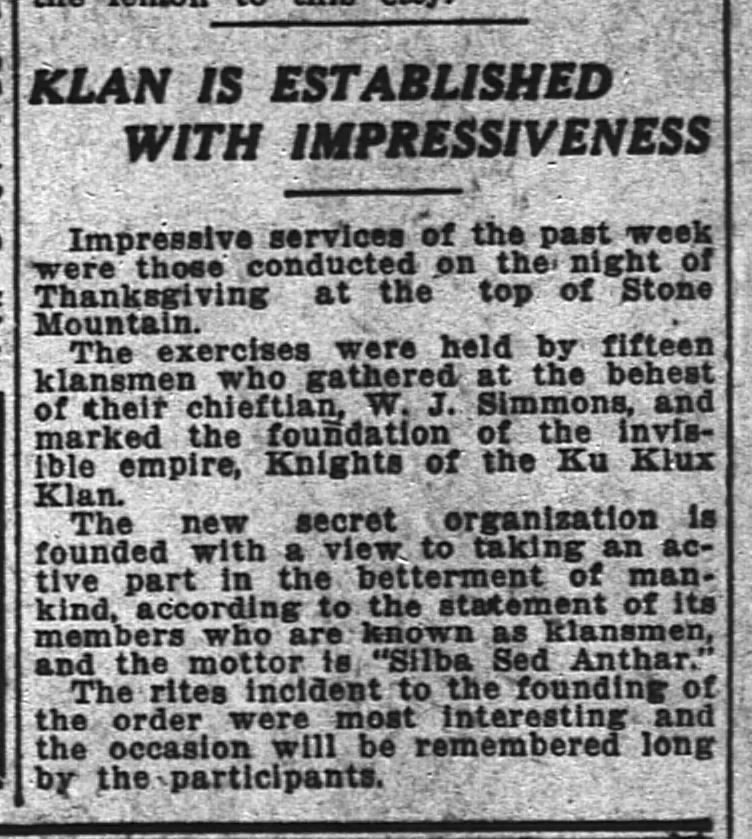

More than a century ago, Stone Mountain was home to the “rebirth” of the Ku Klux Klan, wrote Stephannie Stokes for WABE in 2015. In 1915, a group of racist vigilantes led by preacher William Joseph Simmons gathered near the base of the park’s granite mountain, burned a cross and planted the seeds of revival for the hate group that had terrorized Black Americans in the wake of the Civil War. At its height, this new iteration of the Klan grew to include more than 4 million secret members across the nation.

Today, the site’s legacy continues to inspire white nationalists, according to Stone Mountain Action Coalition, a grassroots activist group dedicated to creating a “more inclusive” park. Many Georgians, including some speakers at Monday’s meeting, argue that the proposed changes do not go far enough to address the park’s role as a symbolic and functional gathering place for racist organizations.

Bona Allen, a representative of the coalition who spoke at the meeting, urged board members to take immediate action.

“You, this board, have the responsibility to the citizens of the state of Georgia—all the citizens of Georgia—to do what’s right right now,” he said, per the AP. “You have the authority, you have the ability, you have the obligation to remove these symbols without delay.”

Stone Mountain boasts the largest Confederate monument—and largest bas-relief artwork—ever erected: a 190- by 90-foot depiction of General Robert E. Lee, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, all of whom are shown on horseback.

This carving and many other Confederate symbols were constructed and funded in the 20th century by women’s and veterans groups in the South, notes the AP. Caroline Helen Jemison Plane, founder of a local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, first proposed Stone Mountain’s enormous carving in 1914, according to Emory University, which holds a collection related to the park in its library.

Tight budgets delayed the work until the 1950s, when the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision spurred Georgia’s segregationist governor, Marvin Griffin, to redouble efforts to memorialize Confederate history in the state. At his urging, officials founded the SMMA and purchased the surrounding land to create a park honoring the Confederacy, wrote Debra McKinney for the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) in 2018. The monumental carved relief was completed and unveiled to the public in 1970.

Discussions over Stone Mountain’s fate arrive amid a renewed reckoning with the nation’s public Confederate symbols. Last year, protests across the United States prompted officials and activists to remove or rename at least 168 Confederate symbols in public spaces, according to records maintained by the SPLC. All but one of those removals took place after a white police officer killed Black Minneapolis man George Floyd in May 2020, reported Neil Vigdor and Daniel Victor for the New York Times in February.

Stone Mountain’s symbolic and historic ties to white supremacist groups were so strong that Martin Luther King Jr., in his famed “I Have a Dream” speech, referenced the site by name. As the civil rights leader neared the end of his 1963 address, he described locations where he envisioned a future free from racial injustice, including the “snow-capped Rockies of Colorado” and the “curvaceous slopes of California.”

“But not only that,” King added. “Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia; let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee; let freedom ring from every hill and mole hill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)