Inside Contemporary Native Artist Rick Bartow’s First Major Retrospective

‘Rick Bartow: Things You Know But Cannot Explain’ arrives at the Autry Museum of the American West

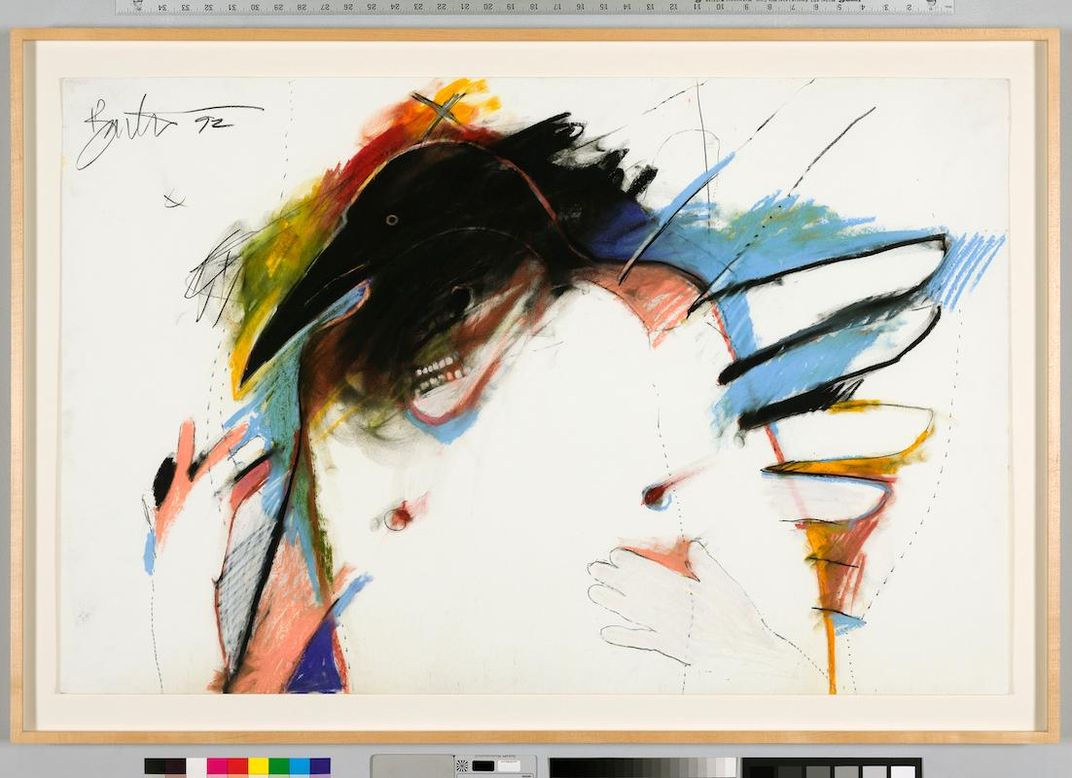

When asked to describe the great Rick Bartow, gallerist and longtime friend Charles Froelick explains the contemporary Native artist didn’t see himself as a “conceptual artist” but rather as an interpreter who “tells stories through marks and images.”

His “stories” have gone on view everywhere from the Smithsonian to the White House.

But it took until 2015—one year before he died of complications due to congestive heart failure— for Bartow to be honored with his first major retrospective. Over the weekend, the traveling show debuted at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles.

“Rick Bartow: Things You Know But Cannot Explain” includes more than 100 sculptures, paintings, drawings and prints dating back to 1979. Together, the compilation of themes in the show, “Gesture,” “Self,” “Dialogue,” “Tradition,” “Transformation,” and “New Work,” weaves together a larger narrative of Bartow’s life and artistic achievements.

Born in 1946 in Newport, Oregon, Bartow was a member of the Wiyot tribe, which is indigenous to Northern California. His paternal ancestors, however, were forced to flee the state during the genocide of indigenous peoples that followed the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848.

Bartow’s mother was Anglo, and Froelick said Bartow saw himself as straddling both worlds. “His mother would take him to church Sunday morning and then he would go to pow wow in the afternoon. He said, you know, you can’t deny one or the other parent.”

After graduating from Western Oregon University with a degree in secondary art education, Bartow was drafted to Vietnam in 1969. He found ways of expressing himself through art overseas, for instance, drawing in the margins of yellow notepads. A talented musician, he also played guitar and sang in a touring GI band, morale-boosting work that earned him a Bronze Star.

When Bartow was discharged in 1971, however, he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and survivor’s guilt. In addition to conventional therapy, he told Marc Leepson of the Vietnam Veterans of America in a 2003 interview that it was art that helped him find himself again.

Explaining his process to Leepson, Bartow said he was always searching for metaphors in his art. "And then sometimes things happen, and I follow the lead. And in the end, I'm dealing not only with part of me that's Native American but also the part of me that is a veteran. It doesn't seem like you ever get rid of that stuff.''

“[He] filters everything through his personal experiences and family heritage," adds Froelick in a blog post for the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. "He is also a voracious looker, poring over art books like no one I know.”

The Autry's chief curator Amy Scott expands on Bartow's influences. In a press release for the exhibition, she says Bartow considered "images and imaginings from Native Northwest culture and artistic traditions and contemporary practices from around the world, including Japan, Germany, and New Zealand” in his work.

The result, the Autry writes, allows Bartow's art to speak beyond "the notions of Western and Native art, realism and abstraction, and the traditional and contemporary." See for yourself: “Rick Bartow: Things You Know But Cannot Explain” will run at the Autry through January 2019.