The Clever Way the Easter Island Statues Got Hats

A new analysis of the 13-ton red stone pukao show the carvings were likely rolled up ramps to the leaning statues

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/76/32761e55-4259-491b-9315-eca02953c167/easter_island.jpg)

It sounds like a riddle: How did the moai, the giant stone carvings on Easter Island, get their hats?

In fact, it’s a legitimate conundrum. Somehow, the native Rapa Nui people cut stone from a quarry and moved the massive blocks distances as far as 11 miles throughout the island. In total, they created 887 of these statues, with some weighing over 80 tons. Each of these moai were adorned with 13-ton hats made of a different type of stone that came from a separate quarry.

Now, reports Kat Eschner at Popular Science, researchers think they’ve figured out just how the Easter Islanders got those massive toppers, called pukao, up there.

The new study, which appears in the Journal of Archeological Science, came about because a team of anthropologists and physicists wanted to ground their hypothesis in the archeological record.

“Lots of people have come up with ideas, but we are the first to come up with an idea that uses archaeological evidence," Sean W. Hixon, a graduate student in anthropology at Penn State and lead author of the study, says in a press release.

Hixon and his team worked under the assumption that the hats were all produced in a similar manner and placed on the moai using the same technique. So they looked for common features in the hats, creating detailed 3-D scans of 50 of the pukao found across the island as well as 13 cylinders of the red scoria rock found at the quarry where the hats were cut. What they found is that, besides their round shape, all the hats also include an indentation where they fit on the head and all the statues sit on similarly shaped bases.

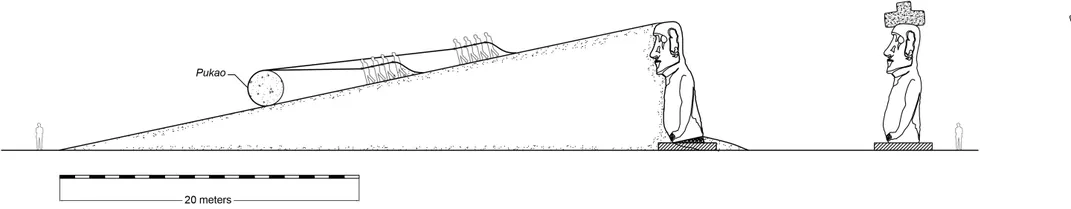

Using this information, the team believes that the hats were rolled from the quarry to the site of the moai. Instead of being put on top of the head while the statue was lying down, as some researcher have proposed, they hypothesize that a ramp made of dirt and rocks was built to the top of the statue, which was tilted forward at a roughly 17 degree angle. Two teams of people would then pull the hat up the ramp using a technique called parbuckling, which allows the heavy stone to be rolled up the ramp without rolling back down.

George Dvorsky at Gizmodo reports that technique would allow a group of as little as 10 or 15 people to move the pukao, which was then further modified at the top of the ramp, something evidenced by shards of the red scoria found at the base of some moai. The hat was then turned 90 degrees and levered onto the statue’s head and the ramp was removed, forming wings on either side of the moai that still exist. In the final step, the base of the statue was then carved flat, causing it to sit upright with the fetching hat on top of its head.

While figuring out just how people created such monumental stone works before the advent of cranes and modern machinery is interesting, it challenges current assumptions about the ultimate fate of the Rapa Nui people. In recent years some historians have suggested that the inhabitants of the island were in such a fever to create the stone statues to their gods and ancestors that they used up all their resources, cutting down the palm forests that once covered the island to transport the stones, leading to resource depletion, starvation, civil war and cannibalism.

But a previous study in 2012 by the same group of researchers found that it’s likely the giant statues were engineered to be moved by rocking them back and forth. That technique does not require vast amounts of timber and uses relatively few people. That, along with the new research on the hats depicts a tradition that undoubtedly took some effort and planning, but wasn’t so overwhelming that it destroyed a society.

“Easter Island is often treated as a place where prehistoric people acted irrationally, and that this behavior led to a catastrophic ecological collapse,” anthropologist Carl Lipo of the University of Binghamton says in another press release. “The archaeological evidence, however, shows us that this picture is deeply flawed and badly misrepresents what people did on the island, and how they were able to succeed on a tiny and remote place for over 500 years…While the social systems of Rapa Nui do not look much like the way our contemporary society functions, these were quite sophisticated people who were well-tuned to the requirements of living on this island and used their resources wisely to maximize their achievements and provide long-term stability.”

So what actually happened to Easter Island and its inhabitants? Catrine Jarman of the University of Bristol writes at the Conversation that the colonizers of the island, likely Polynesian sailors, brought with them Polynesian rats, which ate seeds and sapling palm trees, preventing the forests from sprouting back after sections were cut. And there is no evidence of population crash before European contact. Instead, she writes, disease as well as several centuries of the slave trade reduced the island’s population from thousands to just 111 people by 1877.