The Chicago Field Museum Celebrates the Work of African American Taxidermist Carl Cotton

Cotton started working at the museum in the late 1940s, but he first became interested in taxidermy much earlier

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/ba/e5bac0a0-f0c7-4251-aafa-3028b4bf5bad/2020_march3_taxidermist.jpg)

When Carl Cotton wrote to the Chicago Field Museum in 1940 to ask about job openings, he described himself as an amateur taxidermist. Referencing his interest in reptiles, Cotton mentioned that he had recently acquired a collection of 30 venomous and non-venomous live snakes. Then 22 years old, married and a father of two, he had been performing taxidermy since his childhood years on Chicago’s South Side. Citing Cotton’s lack of an advanced degree, however, the museum turned him down.

After serving in World War II, Cotton reached out to the museum again, this time to offer his services as a volunteer. Museum staff agreed, and he proved to be so good at the job that they brought him on full-time just five weeks later. Cotton’s 1947 hiring marked the beginning of his nearly 25-year tenure at the Field Museum. Prior to his death in 1971, he spent his days preserving animals, repairing specimens and creating exhibits at the Chicago institution.

Taxidermy works aren’t typically labeled with the names of their creator, so Cotton’s influence on the museum was largely lost to history until last year. Now, his work is at the center of a new Field Museum exhibition: “A Natural Talent: The Taxidermy of Carl Cotton.”

Budget coordinator Reda Brooks found a photograph of Cotton in the museum’s 125th anniversary book while preparing for Black History Month. She then showed the snapshot to exhibitions developer Tori Lee, who recounted the experience in a recent blog post.

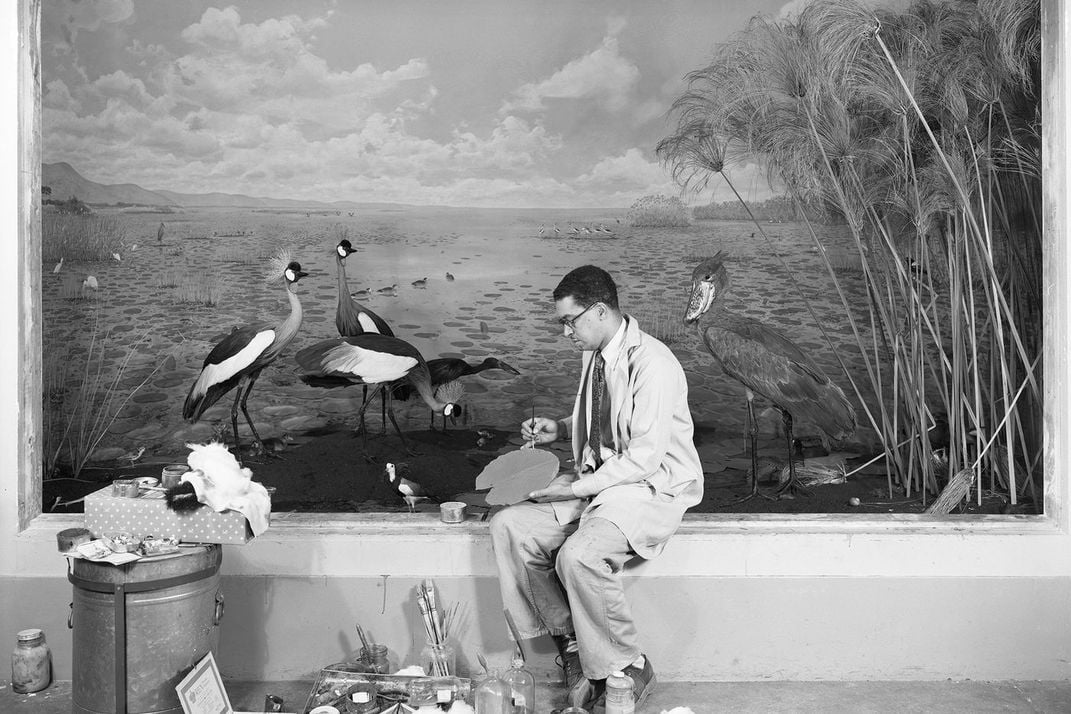

In the image, Cotton sits next to an in-progress diorama of birds in a Nile marsh, carefully sculpting a lily pad by hand.

“A million questions flashed through my mind,” Lee tells the Daily Northwestern’s Aaron Wang. “How in the world did a black man become a taxidermist back then? The Field Museum wasn’t known for being inclusive in that time period. I had to figure out who this was.”

Lee went to the archives, where she and her colleagues found Cotton’s letters to the museum and reports that detailed his assignments. After posting calls for information on social media, she attracted the attention of Cotton’s family and old friends, who shared more of his story. He had reportedly been interested in taxidermy from a young age, catching and stuffing urban critters like squirrels and birds, as well as immortalizing dearly departed pets.

Cotton’s old friend Timuel Black, a Chicago historian and activist, tells Lee that “cats and rats ran when they saw Carl.”

The museum team also discovered videos of Cotton preparing exhibits such as the Marsh Birds of the Upper Nile diorama. His earliest assignments centered on birds, and he prepared about a quarter of the specimens now on view in the Field Museum’s bird hall, according to Emeline Posner of Chicago magazine. Later, Cotton also worked on large mammals, insects, and notoriously difficult animals like reptiles and fish.

“Most of the taxidermists specialize in one species, but he did everything he had at the time,” Mark Alvey, the museum’s academic communication manager, tells the Daily Northwestern. “You can see he really started to grow his skills and how much he did.”

Per the museum’s educational YouTube channel, BrainScoop, he and colleague Leon Walters learned to create sculptural replicas of animals using an early plastic called celluloid. With time, Cotton improved on the technique and taught it to others.

He “went above and beyond” typical taxidermy of the time, explains Lee to Atlas Obscura’s Sabrina Imbler.

The taxidermist even practiced his craft at home, storing specimens in the freezer and using a built-out part of his garage (and later a bathroom) to create his projects.

“Everything was in there—bear skin rugs, fish that he had caught that he decided he was going to work on and keep,” grandson Carl Donn Harper tells Chicago magazine. “My mother would take me by, and while the adults would be up front, having coffee and talking, I’d be in the back exploring.”

In addition to staging the exhibit, the museum has labeled all of its pieces known to be Cotton creations. By sharing his story, says Lee, the museum can expand what people think is possible.

“I want people to feel like they can work here [at the Field],” explains Lee to Chicago magazine. “That they can do different things that may seem weird to other people, or things that they didn’t even know existed.”

“A Natural Talent: The Taxidermy of Carl Cotton” is on view at the Field Museum in Chicago through October 5, 2020.