Chemist Hazel Bishop’s Lipstick Wars

Bishop said her advantage in coming up with cosmetics was that, unlike male chemists, she actually used them

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/46/85460c85-936f-4267-b21c-2564c3312ccd/istock-139377608.jpg)

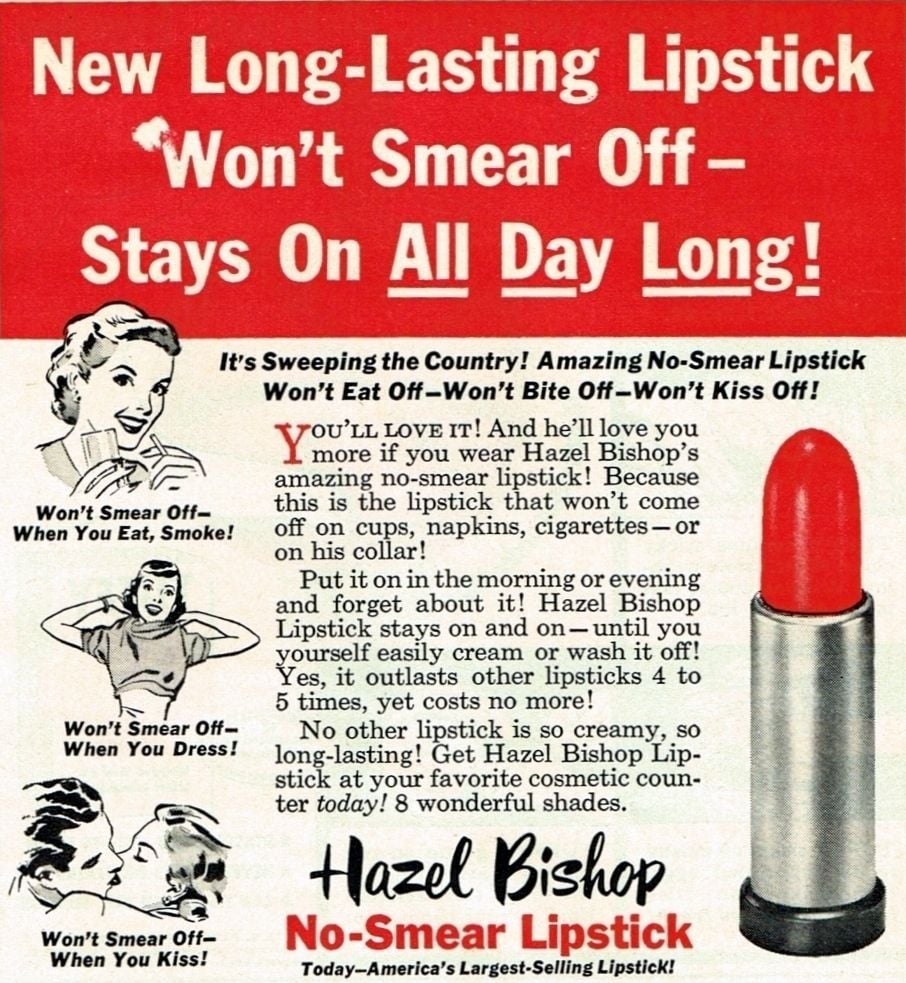

Gone were the days of cheek-prints and constant reapplications when Hazel Bishop came up with the first kissproof lipstick.

Early lipsticks tended to leave less-than-desirable smudges on cups, cigarettes and teeth, wrote Mary Tannen in Bishop’s 1998 New York Times obituary. But the industrial chemist’s new formula didn’t leave marks–and didn’t have to be reapplied throughout the day. It made Hazel Bishop into a wealthy and successful businesswoman–but Bishop’s innovation didn’t remain hers for very long.

Bishop, who was born on this day in 1906, was set on the path to makeup moguldom when she got a job assisting a Columbia University dermatologist, writes Columbia. Already armed with an undergraduate degree in chemistry, “she was able to take graduate courses in biochemistry while working on [the dermatologist]’s ‘Almay’ line of hypoallergenic cosmetics,” the school writes.

“Women have an insight and understanding of cosmetology a male chemist can never have,” she once said. “Does a man, for instance, know what happens to makeup under the hot beach sun?”

Bishop was right that she had an unusual angle on the cosmetics business, which enabled her to see problems that other chemists who didn’t wear makeup could not. After the war, she was still working on gasoline formulations, writes Columbia–but in her own time she came up with long-lasting lipstick, reportedly in her own kitchen.

“By 1949 she found the solution–a stick of bromo acids that stained skin rather than coating it,” writes Columbia. The lipstick wasn’t irritating, it didn’t make lips dry or cracked-looking and it stuck, wrote Tannen. In 1950, with the help of an investor, she was able to form her own company, Hazel Bishop Inc., which manufactured her lipstick.

“When it was introduced that summer at $1 a tube, Lord & Taylor sold out its stock on the first day,” wrote Tannen. (That’s about $10.50 in today’s money.) This rampant popularity sparked the “lipstick wars,” wherein established cosmetic companies such as Revlon, which helped pioneer nail polish, tried to replicate Bishop’s success.

In 1951, the Madera Tribune ran a profile of Bishop and her new lipstick, which prevented “‘tattle-tale red’ on a man’s shirt collar.” At the time, Bishop’s lipstick was reported to be the second-most popular in the nation, and had inspired many imitators.

“It pleases me to see every other cosmetics maker following my lead,” the “modest, soft-spoken” chemist said, according to the Tribune. Later that year, she appeared solo on the cover of Business Week–the first woman to do so.

But trouble was on the way for Bishop in the form of another kind of lipstick war. She was pushed out of her own company by shareholders, even as it blossomed. Raymond Spector, the "advertising pro" who had helped her launch her company, had been paid in company stock. "He helped her form the idea of calling it 'kissable' lipstick," writes Lemelson-MIT, but he also took her valuable company. "An unfortunate dispute between her and Spector resulted in a lawsuit and the loss of her position [in late 1951]," Lemelson-MIT writes. By 1954, when the lawsuit was finally settled, she'd moved on. Bishop, she went on to have a long and successful career, first in chemistry, then in other pursuits. In the 1960s, she even became a stockbroker herself–specializing in cosmetics stocks.