Celebrate 50 Years of International Literacy Day With the British Library

Butterflies, rabbits and Shakespeare: there’s something for everybody

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/52/8952107f-d991-4b67-9a19-4edc19b33193/15657137102_c32f808dde_k.jpg)

Fifty years ago, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared the first International Literacy Day. The idea was to draw attention to the importance of reading and writing around the world. Though global literacy rates continue to be on the rise, as a UNESCO report shows, some 758 million adults remain illiterate.

That makes this year’s festivities all the more relevant. To celebrate International Literacy Day, Smithsonian.com has picked a few gems out of the British Library’s digitized collection, which highlight the many aspect of literacy:

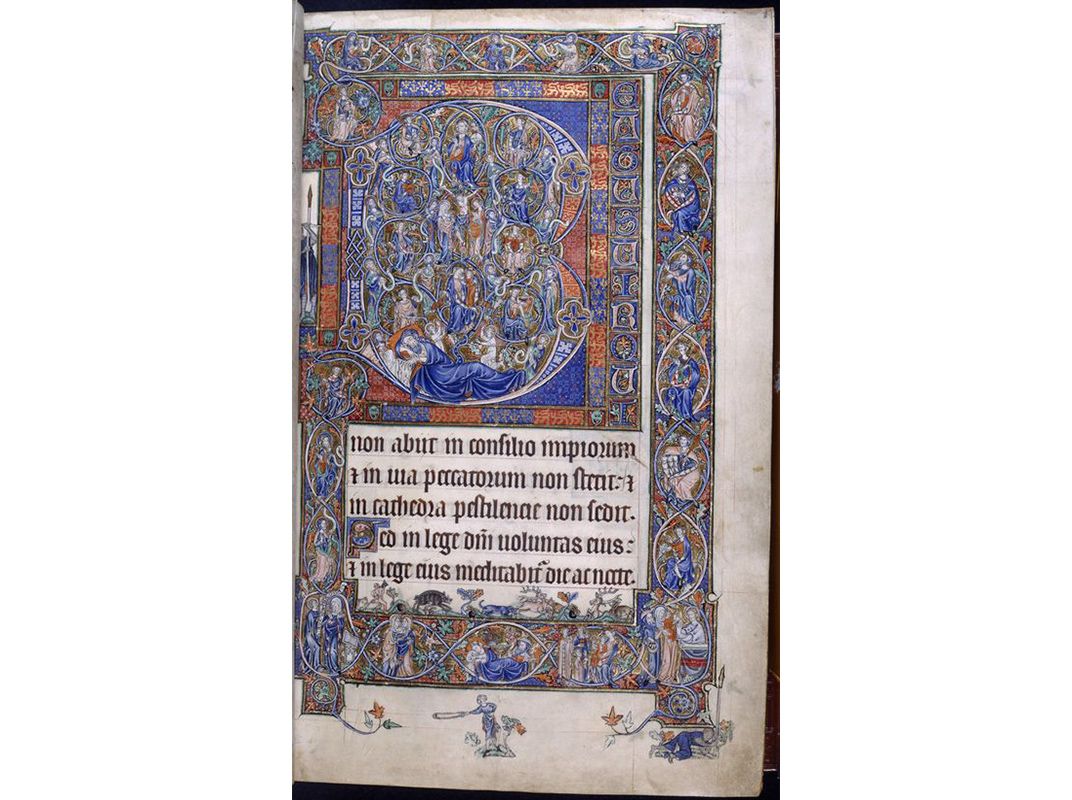

Gorleston Psalter, Creator unknown (circa 1310 CE)

This Psalter, or book of psalms, might have been created by an unknown author for an unknown person, but scribbles in the margin make the tome anything but anonymous.

As Sarah J. Biggs points out in a British Library blog post, the bearded man who appears in the marginalia is a possible candidate for the book’s patron. One idea is that he might be Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk. Today, historians also suspect John de Warenne, 7th Earl of Surrey seeing as his coat of arms can be seen throughout the manuscript, and the images of rabbits that appear throughout might be a pun on his last name. (Warrens are the system of burrows that rabbits live.)

A look through the margins of this text also shows the wide range of subjects that marginalia could deal with—everything from grotesques and toilet humour to everyday life, all nestled next to a holy text. Another British Library blog post about this manuscript by Biggs talks about how the Gorleston Psalter shows examples of the monde renversé, or upside-down world, where rules are reversed and the line between humans and animals becomes unclear. That explains why there’s an image of rabbits carrying a coffin in a funeral procession included in the book.

Drawings of lepidopterous insects, Elizabeth Dennis Denyer (1800 CE)

This printed collection of butterfly and moth paintings is both beautiful and edifying. According to a British Library blog post by Sonja Drimmer, Elizabeth Dennis Denyer, a restorer of medieval manuscripts and early printed books, donated her book of butterfly paintings to the British Library during the 19th century. But the work was not studied until Drimmer, a lecturer at Columbia University, found the work during her research of Denyer. As it turns out, the work was based on the specimens of Denyer’s neighbor, a renowned entomologist named William Jones. Drimmer and Dick Vane-Wright authored a study of the insect images, and their findings suggest a historical connection between antiquarianism and the study of insects (entomology). The research is important but the manuscript is also lovely in its own right.

The Booke of Sir Thomas Moore, collaboratively written by Anthony Munday and others (circa 1601-1604)

This text contains the only identified example of a play script with some of William Shakespeare’s own handwriting. Scholars believe the Bard wrote three pages of The Book of Sir Thomas More after he was brought in to revise the manuscript originally written by Anthony Munday at some point between 1596 and 1600. Following the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, Shakespeare and three other playwrights were asked to revise the text by the Master of Revels Edmund Tilley. The reason? Tilley was concerned the play, which addresses the events of the May Day riots of 1517 would provoke, in the words of the British Library, “civil unrest.”

Listen to Ian McKellen read one of the passages, which the British Library believes was written by Shakespeare:

Hungry for some more artifacts? Not to worry. You can also tour the British Library using Google Street View.