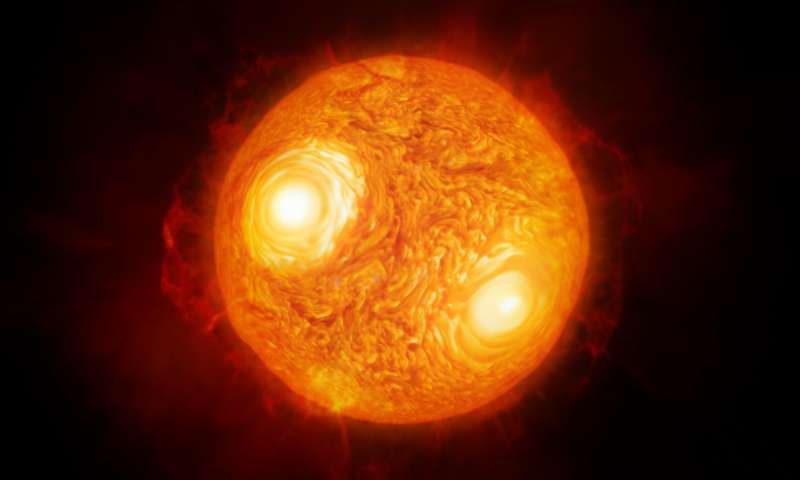

This Is the Best Image of a Star Beyond Our Solar System (Yet)

A detailed convection map of the red supergiant Antares is spectacular, but it also shows we don’t know everything that’s going on

There’s a race going on in astronomy to get the best picture of distant star. In June, researchers announced they had used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile to capture the most detailed image of star (apart from our sun), getting a good look at Betelgeuse. Now, a new study of the star Antares has yielded an even better image, reports Ian O’Neill at Space.com, and it’s raised some big questions about the star itself.

Antares, a red star in the constellation Scorpio roughly 600 light-years from Earth is one of the brightest lights in the night sky. That’s because the star is a red supergiant, a star reaching the end of its life that begins to puff up, sometimes 100 to 1,000 times larger than our own sun. Eventually, sometime in the next few thousand years, Antares will go supernova, exploding across the night sky.

Antares is about 15 times as massive as our sun and 850 times its diameter, rapidly venting mass into its upper atmosphere on its journey towards star death, reports Hannah Devlin at The Guardian. But just how and why stars lose that mass is not well understood. That’s why Keiichi Ohnaka, of the Universidad Católica del Norte in Chile and his team trained the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI) on Antares to create a new image with layers of detail.

“How stars like Antares lose mass so quickly in the final phase of their evolution has been a problem for over half a century,” Ohnaka says in a press release. “The VLTI is the only facility that can directly measure the gas motions in the extended atmosphere of Antares—a crucial step towards clarifying this problem. The next challenge is to identify what’s driving the turbulent motions.”

Using three of the VLTI’s telescopes and an instrument called AMBER that measures infrared light, the team was able to gather observations over five nights in 2014. Combining them together using a specialized algorithm, they created a velocity map of the gases in the star’s atmosphere, something never done before for a distant star. The research appears in the journal Nature.

“Before, we just saw the temperature of the surface of the star, and how it may be different on one part or another part,” University of Michigan astronomer John Monnier, not involved in the study, tells Doris Elin Salazar at Space.com. “But this really gives you velocity, the speed of that surface as it’s coming towards or away from you. That has never been done before on a surface of a star. This is kind of a pioneering dataset to be able to do that.”

The data also raises a conundrum, reports Ryan F. Mandelbaum at Gizmodo. The convection currents in the star’s atmosphere don’t account for all the mass being flung beyond the star's surface. In fact, some of the gas in the upper atmosphere is moving at 20 kilometers per second, reaching 1.7 times the stars radius. That’s much faster and further than researchers found occurring on Betelgeuse. The astronomers currently don’t know what process is moving all that matter, but hope more observations will solve the mystery.

“The most intriguing part of the new observation is that it unveils the remarkable complexity of physical processes that take place in the atmospheres of such stars,” Maria Bergemann of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany tells Mandelbaum. “This motivates better models which can be used to infer more accurate information about the life cycles of these stars, thus making interesting predictions for how the stars live and when they die.”

In the press release, Ohnaka says he hopes the new observation technique will be applied to other stars and lead to a deeper understanding of stellar atmospheres.