Beads Made From Meteorite Reveal Ancient Trade Network

Researchers have confirmed iron beads in Illinois come from a Minnesota meteorite, supporting a theory called the Hopewell Interaction Sphere

In 1945, archaeologists opened a 2,000-year-old Hopewell Culture burial mound near Havana, Illinois, and discovered 1,000 beads made of shell and pearl. They also found 22 iron-nickel beads which they determined came from a meteorite. But iron meteorites in North America are rare, and it wasn’t clear just which space rock the beads were related to, reports Traci Watson at Nature.

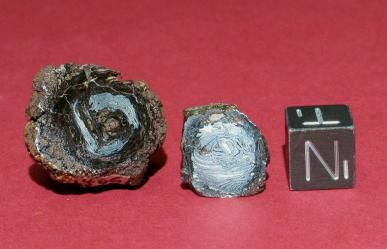

A few years later, in 1961, a meteorite was found near Anoka, Minnesota, a town along the Mississippi River. At the time, chemical analysis ruled out that lump of iron as the source of the beads. Then, a second piece of the same meteorite was discovered in 1983 across the river from the original.

Timothy McCoy, curator in charge of meteorites at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, tells Smithsonian.com that a consortium of museums spearheaded by the National Museum of Natural History bought the 90-kilogram chunk in 2004. While doing an inventory of the meteorite collection at the museum in 2007, he was reminded that the museum owned two of the Havana meteorite beads. He decided to compare the composition of the newer Anoka meteorite with those beads as well as take another look at the original chunk. Mass spectrometry analysis showed that the composition of the beads and the space iron was a near-perfect match. The research appears in the Journal of Archeological Science.

"I think it’s pretty solid evidence," says McCoy. "We have 1,000 iron meteorites and there are only 4 that are possibly related to the beads. One is in Australia, ruling that out, and the others are in Kentucky and Texas. But they differ enough in composition to make me think they are not the parent material."

McCoy says that "fingerprints" left on the surface of the chunks caused by cosmic radiation indicate that the original meteorite was roughly 4,000 kilograms. That means it's likely the meteorite rained down chunks of iron from the sky across the upper Midwest, though those pieces are probably buried (the fragments that have been found were dug up during sewer and road projects). He thinks the beads came from another lump of the meteorite found by people from the Hopewell culture.

The new study not only confirms the origins of the beads, but also shows just how extensive prehistoric trading networks were. Kelsey Kennedy at Atlas Obscura reports that while the discovery wrapped up the mystery of the beads origins, it spawned others. For one, how did the iron travel so far from the site of the meteor? And how did a culture that had no experience with iron working create the beads?

Léa Surugue at The International Business Times reports that anthropologists have two competing theories about the economic and social organization of the Hopewell, a culture that stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the East Coast at one point. Researchers have found some pretty incredible artifacts in graves and village sites, including at the main Hopewell cultural center near Chillicothe, Ohio. At that site, believed to be a religious and pilgrimage site, archaeologists have recovered shark teeth from the Gulf Coast, obsidian from Yellowstone and silver mined near the Upper Great Lakes.

One theory called the Hopewell Interaction Sphere suggests that the Hopewell traded these objects from village to village in a vast trading network that spanned the continent. The other model is direct procurement, in which people traveled on long expeditions from their villages to gather exotic metals and other resources. McCoy tells Surugue that he thinks the meteorite beads support the Interaction Sphere hypothesis. “Meteorites are exceptionally rare objects. While it might make sense for an individual to travel to the site of large copper deposits and bring back material, it is difficult to reconcile that kind of model with something like a meteorite,” he says. “By establishing a link between Anoka, Minnesota and Havana, Illinois – two places within reach of known Hopewell centers and connected by major river systems – the trade model seems much more plausible.”

Kennedy reports that it’s possible that the Havana Hopewell got the iron from the Trempelau Hopewell to the north who may have discovered a fist-sized lump of the iron. Watson reports the Havana likely didn't get the metal through trade, though, but that the precious iron might have been used as a gift to ratify an alliance or was brought by religious pilgrims.

But McCoy tells Smithsonian.com the Havana beads are just one small piece of evidence for the trade network. In Chillicothe, researchers have found tons of objects made from a meteorite that fell in Kansas, including axe heads, pounding stones and beads. "They may have had two mechanisms in two places," he says. "They may have had expeditions going to Kansas and bringing back iron while the Anoka meteorite was acquired through trade. The Hopewell loved exotic objects and meteorites were the most exotic. In Hopewell culture these beads had the rarest of rare materials."

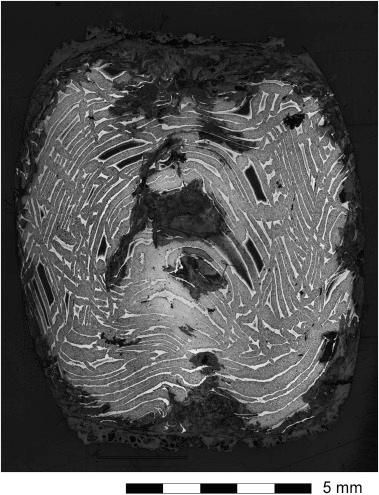

So how were the beads made? McCoy says it's likely the Hopewell adapted the methods they used to work copper and silver to working with the iron. As he tells Watson, when the meteorite metal is shot through with a mineral called schreibersite, it allows it to be broken apart. McCoy first tried to simulate a bead by using constant heat and steel tools to work on a chunk of the meteorite, but the method was too efficient and did not produce the same microtexture as the original beads. But when he used methods available to the Hopewell, heating the iron in a wood fire and heating and pounding it in repeated cycles, he was able to produce a bead very similar to the Havana beads. Watson notes that the method is similar to the way the Egyptians crafted beads out of meteorite iron 3,000 years ago.