3-D Images Show Just How Much a Baby’s Head Changes During Birth

Scientists behind a new study were surprised by the degree of stress that is placed on a baby’s skull as it moves through the birth canal

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/1a/b01a5cf5-41cf-4bcb-8684-d3d977d0f1a8/istock-950367804.jpg)

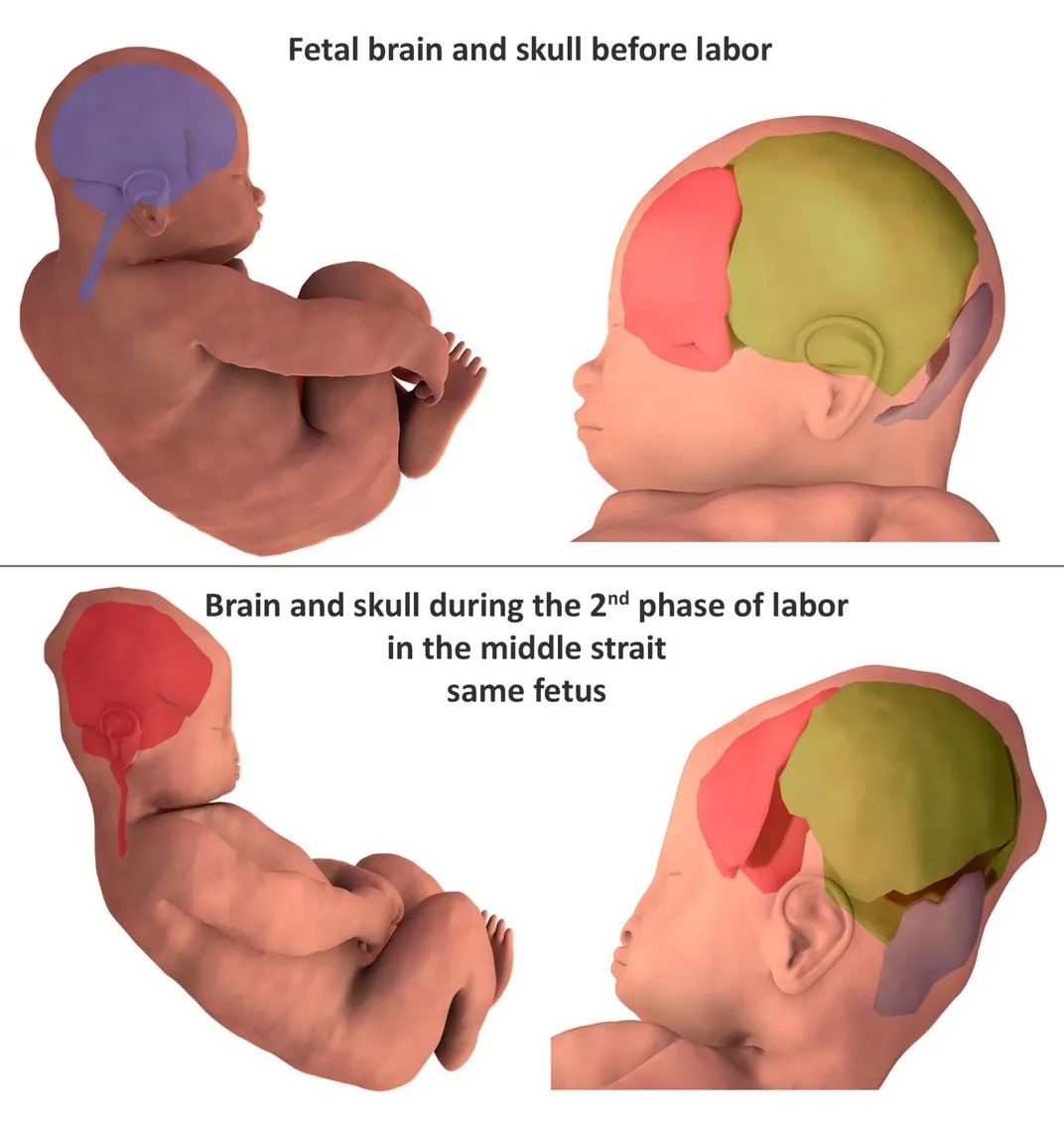

As anyone who has gingerly handled a new baby will know, infants are born with soft skulls. their heads need to be a bit squishy in order to make it through the relatively narrow birth canal. But the details of “fetal head molding,” as doctors call the shape changes that occurs to babies’ heads during labor, are not well understood. It isn’t easy, after all, to peek inside a mother as she is giving birth.

But as Mindy Weisberger reports for Live Science, researchers in France have done just that. For a new study published in PLOS One, medical experts used 3-D M.R.I. to capture remarkably detailed images of babies’ skulls and brains during advanced stages of labor. Their findings suggest that infants’ little noggins undergo considerable stress during birth—more so than experts had previously thought.

Twenty-seven pregnant women consented to recieving M.R.I. scans before they gave birth, and of those, seven agreed to be scanned during the second stage of labor—the period between when the cervix has dilated to 10 centimeters and the baby is born. The imaging was performed no more than ten minutes before "expulsory effort," or when the baby descends into the birth canal and mother can begin to push. After the images were taken, the mothers were swiftly rushed to the delivery room; “Patient transportation time from the M.R.I. suite to the delivery room in the same building, bed to bed, was less than three minutes,” the study authors note.

Upon comparing the pre-labor and mid-labor images, the researchers were able to see that all seven babies experienced fetal head molding. This means that different parts of the skull overlapped, to varying degrees, during the birthing process. Infants’ skulls are thus comprised of several bony sections, held together by fibrous materials called sutures, that eventually fuse as the baby grows outside the womb. (Researchers know that skull shifting during birth has been happening in humans and their ancestors for millions of years; it's an adaptation to the evolution of larger brains and the switch to upright walking, which altered the shape of the pelvis.)

Still, the researchers were surprised by just how much babies’ heads were squishing as they moved through the birth canal. “When we showed the fetal head changing shape, we discovered that we had underestimated a lot of the brain compression during birth,” first study author Olivier Ami, an obstetrician and gynecologist at University of Clermont Auvergne in France, tells Erika Edwards of NBC News.

The skulls of five of the babies under observation quickly returned to their pre-birth state, but changes persisted in two of the babies—possibly due to differences in the elasticity of the skull bones and the supporting fibrous material, among other factors. Two of the three babies with the largest degree of head molding still needed to be delivered via C-section, indicating that mothers may not always be able to give birth vaginally, “even when significant fetal molding occurs,” the study authors note.

Interestingly, the third baby among those with the highest degrees of head warping initially scored low on the Apgar test, which is given to babies soon after birth and assesses skin color, pulse, reflexes, muscle tone and breathing rate. By the time the baby was 10 minutes old, however, its score had risen to a perfect 10. The researchers do not yet know how or if ease of delivery—the infant was born vagianally and the delivery was “uncomplicated”—and fetal head molding factors into this “risky clinical presentation,” the study authors note. But it does suggest that we might need to rethink the how we view “normal births,” which are typically defined as natural births that happen with “only a few maternal expulsive efforts.”

“This definition does not take into consideration the ability of the fetal head to deform,” the researchers explain. “If the fetal head’s compliance is high, the skull and brain may undergo significant deformation as the birth canal is crossed, and the child's condition at birth may not be good.”

Revelations about the stresses that come with fetal head molding might also explain why some babies are born with retinal and brain hemorrhages, the latter of which can lead to complications like cerebral palsy, Edwards reports. And though the study is small, the researchers say the high quality imaging could inform efforts to develop a “more realistic simulation of delivery” that will help medical experts predict which mothers are at risk of running into biomechanical complications during childbirth—and intervene before harm comes to the baby.