These Sleek, Sexy Cars Were All Inspired By Fish

You’ve heard about the Stingray, but what about the Bionic Boxfish?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/0e/760eac4e-dafb-4397-bd2d-22dc30661c9b/istock_88066457_medium.jpg)

In 2009, automotive designers at Japanese carmaker Nissan were scratching their heads over how to build the ultimate anti-collision vehicle. Inspiration came from an unlikely source: schools of fish, which move synchronously by sticking close together while simultaneously staying a safe stopping distance apart. Nissan took the aquatic concept and swam with it, creating safety features in Nissan cars like Intelligent Brake Assist and Forward Collision Warning that are still used today.

Biomimicry—an approach to design that looks for solutions in nature—is by now so widespread that you may not even recognize the real-life inspiration behind your favorite technology. From flipper-like turbines to leaf-inspired solar cells to UV-reflective glass with spider web-like properties, biomimicry offers designers efficient, practical, and often economical solutions that nature has been developing over billions of years. But combine biomimicry with sports cars? Now you're in for a wild ride.

From the Jaguar to the Chevrolet Impala, automotive designers have a long tradition of naming their cars after creatures that evoke power and style. Carmakers like Nissan even go so far as to study animals in their natural environments to advance automotive innovation. Here are a few of the most famous classic cars—commercial and concept—that owe their inspiration to the deep blue sea.

A Bubble of One’s Own

While automotive designer Frank Stephenson was on vacation in the Caribbean, a sailfish mounted on the wall of his hotel made him do a double take. The fish's owner was especially proud of his catch, he told Stephenson, because of the fact that sailfish are coveted for being too fast to easily capture. Reaching speeds of 68 miles per hour, the sailfish is one of the fastest animals in the ocean (close competitors include its cousins the swordfish and marlin, all of which belong to the billfish family).

His curiosity hooked, Stephenson returned to his job at the headquarters of British automotive giant McLaren eager to learn more about what makes the sailfish the fastest in the sea. He discovered that the fish’s scales generate tiny vortices that produce a bubble layer around its body, significantly reducing drag as it swims.

Stephenson went on to design a supercar in the fish’s image: The P1 hypercar needs generous air circulation to maintain combustion and engine cooling for high performance. McLaren’s designers applied the fish scale blueprint to the inside of the ducts that channel air into the engine of the P1, boosting airflow by an incredible 17 percent and increasing the efficiency and power of the vehicle.

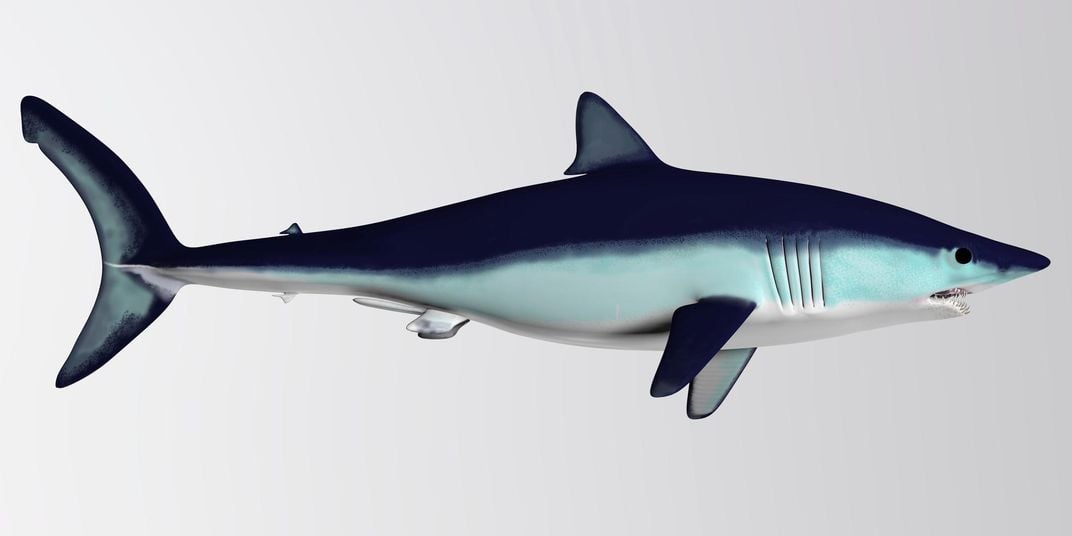

The Road Shark

Out of all the ocean-inspired sports cars, the Corvette Stingray is perhaps the most famous. Colloquially named “The Road Shark,” the Stingray is still produced and sold today. It isn’t the only car to appear in a suite of shark and ray-inspired 'Vettes, however. There's also the Mako Shark, the Mako Shark II and the Manta Ray, although none of these have enjoyed the longevity of the Stingray. Built in the United States, America’s love affair with the Stingray continues today as a race-ready sports car for not a whole lot of money.

Corvette’s aquatic renaissance stemmed partly from one man’s fishing trip. General Motors design head Bill Mitchell, an avid deep-sea fisher and nature-lover, returned from a trip to Florida with a Mako shark—a pointy-nosed apex predator with a metallic blue back—which he later mounted in his GM office. Mitchell was reportedly captivated by the vibrant gradation of colors along the underbelly of the shark, and worked tirelessly with designer Larry Shimoda to translate this coloration to the new concept car, the Mako Shark.

Although the car never went on the market, the prototype alone gained iconic status. But the concept didn’t disappear entirely. Instead, after acquiring a few upgrades, the Mako evolved into the Manta Ray after Mitchell was inspired by the movement of a manta powerfully gliding through the ocean.

A Little More Bite

This iconic fastback almost had an entirely different namesake when Plymouth’s executives lobbied to call the car "Panda." Unsurprisingly, the name was unpopular with its designers, who were looking for something with a little more…bite. They settled on "Barracuda," a title more befitting of the muscle car’s snarling, toothy grin.

Serpentine in appearance, barracudas in the wild attack with short bursts of speed. They reach up to 27 miles per hour, and have been observed overtaking prey larger than themselves using their rows of razor-sharp teeth. Highly competitive animals, barracudas will sometimes challenge animals two to three times their size for the same prey.

The Plymouth Barracuda was hastily brought to market to jump the release of its direct competitor, the Ford Mustang in 1964. The muscle car’s debut was rocky, but it returned in 1970 with an unapologetically fierce body design and a V8 motor. Sleek yet muscly, the Barracuda lives up to its name—a wickedly fast classic car with a predatory instinct.

Misguided by a Boxfish

Despite its goofy-looking exterior, the boxfish represents an amazing feat of bioengineering. Its box-shaped, lightweight, bony shell makes the small fish agile and maneuverable, as well as purportedly aerodynamic and self-stabilizing. Such attributes made it an ideal inspiration for a commuter car, which is why Mercedes-Benz unveiled the Bionic in 2005—a concept car that took technical and even cosmetic inspiration from the spotted yellow fish.

Sadly, the Bionic never made it to market after further scientific analysis on the biologic boxfish’s “self-stabilizing” properties were largely debunked. More research revealed that really, over the course of its evolution the boxfish had given up speed and power for an assortment of defensive tools and unparalleled agility. Bad news for the Bionic—but a biomimicry lesson for the books.

Learn more about the seas with the Smithsonian Ocean Portal.

Learn more about the seas with the Smithsonian Ocean Portal.