Teeth Tales

Fossils tell a new story about the diversity of hominid diets

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/teeth388.jpg)

About two million years ago, early human ancestors lived alongside a related species called Paranthropus in the African savanna. Members of Paranthropus had large molars and strong jaw muscles, and some scientists have assumed that the species ate hard, low-nutrient shrubs and little else.

Anthropologists often consider that limited diet the reason Paranthropus died out one million years ago, whereas early humans, with their more flexible eating habits, survived.

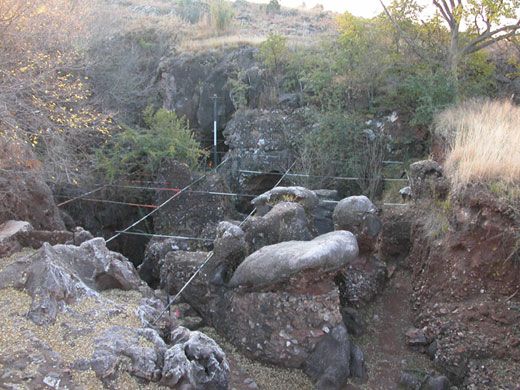

But a new study of Paranthropus fossils suggests a different story. A team of scientists led by Matt Sponheimer of the University of Colorado at Boulder recently analyzed four 1.8-million-year-old Paranthropus teeth found at the Swartkrans Cave — a well-known archeological site in South Africa.

After studying each tooth's enamel with a new technique called laser ablation, Sponheimer's team concludes in the Nov. 10 Science that Paranthropus had a surprisingly varied diet. Far from confined to eating shrubs, trees and bushes, Paranthropus likely had a rich diet that included grass, sedges and herbivores. This diet apparently changed from season to season and even year to year, perhaps enabling Paranthropus to adapt to prolonged droughts.

The success of laser ablation — a far less invasive technique than traditional drilling — should persuade museum curators to allow scientists greater access to teeth fossils, argues anthropologist Stanley Ambrose of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in a commentary accompanying the research paper.

For now, the results give Sponheimer's team a new thought to chew on: some unknown, non-dietary difference must explain the diverging fates of Paranthropus and Homo.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)