Sharks and Humans: A Love-Hate Story

A short history of our relationship with the ocean’s most intimidating fish

If you’ve watched Jaws or the newly released shark thriller The Shallows lately, you’d be forgiven for considering sharks as the universal symbol of human fear. Actually, our relationship with these ancient predators is long and complex: sharks are revered as gods in some cultures, while in others they embody terror of the sea. In honor of Shark Week, the Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal team decided to show how sharks have sunk their teeth into almost every aspect of our lives.

History and Culture

From the Yucatan to the Pacific Islands, sharks play a leading role in the origin myths of many coastal societies. The half-man, half-shark Fijian warrior god Dakuwaqa is believed to be a benevolent protector of fishermen. Hawaiian folk legends tell stories of Kamohoalli’i and Ukupanipo, two shark gods that controlled the fish population, and thus determined how successful a fisherman was. In ancient Greece, paintings depict a shark-like creature known as Ketea, who embodied ravenous and insatiable hunger, while the shark-like god Lamia devoured children. Linguists believe that “shark” is the only English word to have Yucatan origins, and stems from a bastardization of the Mayan word for shark, “xoc.”

Juliet Eilperin, an author and White House bureau chief for the Washington Post, explores the long-standing human obsession with sharks in her 2012 book Demon Fish: Travels Through the Hidden World of Sharks. As humans took to the sea for trade and exploration, deadly shark encounters became a part of seafaring lore, and that fascination turned to fear. “We really had to forget they existed in order to demonize them,” Eilperin said in a 2012 SXSW Eco talk. “And so, what happened is we rediscovered them in the worst possible way, which is through seafaring.”

That fear persisted even on land: In the early 20th century trips to the shore became a national pastime, and in 1916, four people were killed by sharks on the New Jersey shore within a span of two weeks. Soon sharks had become synonymous with fear and panic.

In 1942, fear of sharks among sailors and pilots was serious enough to warrant a major Naval investigation into ways to deter their supposed threat by major research institutions, including Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Scripps Institute of Oceanography, the University of Florida Gainesville and the American Museum of Natural History. The endeavor produced a shark repellant known as “Shark Chaser,” which was used for nearly 30 years before ultimately being deemed useless. Shark Chaser falls in a long line of failed shark repellants: The Aztec used chili to ward away these fish, a remedy whose effectiveness has since been discredited (the Aztecs probably found that out the hard way). Today, there are a variety of chemical- or magnet-based shark repellants, but they are generally limited to one or a few species of sharks or just don’t work, as Helen Thompson wrote last year for Smithsonian.com.

In reality, sharks are the ones who need a repellent: humans are much more likely to devour them than vice versa. In China, a meal of shark fin soup has long served as a status symbol—a trend that began with Chinese emperors, but more recently spread to middle class wedding tables and banquets. The demand for sharks to make the $100-per-bowl delicacy, coupled with bycatch in other fisheries, has led to sharp declines in shark populations: a quarter of the world’s Chondrichthyes (the group that includes sharks, rays and skates) are now considered threatened by the the IUCN Red List. Yet there is hope for our toothy friends: While Hong Kong is still the leading importer of shark fins around the globe, demand and prices are dropping. New campaigns in China are attempting to curb the nation’s appetite for shark fin soup, and shark protections and regulations have increased in recent years.

Art

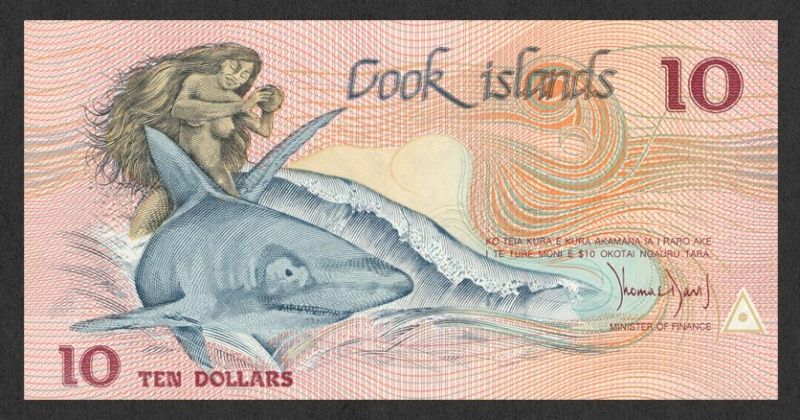

Sharks have long inspired artists from around the world, beginning with Phoenician potters working 5,000 years ago. In the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia in the mid-1700s, indigenous people decorated mortuary totem poles with elaborate woodcarvings of sharks and other sea animals. As the fur trade brought with it wealth and European tools, tribe leaders began to assert their power and status through these poles, and by 1830 a well-crafted pole was a sign of prestige. The Haida of British Columbia’s Queen Charlotte Islands commonly included dogfish (a type of shark) and dogfish woman on their totem poles. Kidnapped by a dogfish man and carried out to sea, the fabled dogfish woman could transform freely between human and shark form and became a powerful symbol for people who claimed the dogfish mother as their family crest.

Around the same time as totem poles were gaining popularity in America, a shark-inspired painting had captured the fascination of the European artistic elite. In 1776, a painting called Watson and the Shark by Boston-born John Singleton Copley began making waves at London’s Royal Academy. Commissioned by Brook Watson, the painting depicted the 14-year-old Watson being attacked by a shark off the coast of Cuba—a true story which had occurred 30 years earlier, and resulted in the loss of the commissioner’s lower leg. The encounter impacted Watson deeply: when he became a baronet in 1803, he made sure to include a shark in his coat of arms.

In modern times, artists continue to be inspired by sharks, as witnessed by Damian Hirst’s innovative piece The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. Suspended in a glass tank of formaldehyde, a 13-foot tiger shark appears to be staring at viewers despite being very much dead. (The original 1991 specimen was replaced with a slightly smaller specimen in 2006 due to poor preservation and the resulting decay of the shark.) In Death Explained, a piece Hirst created in 2007, two glass-and-steel tanks display the inner anatomy of actual tiger sharks.

Science and Technology

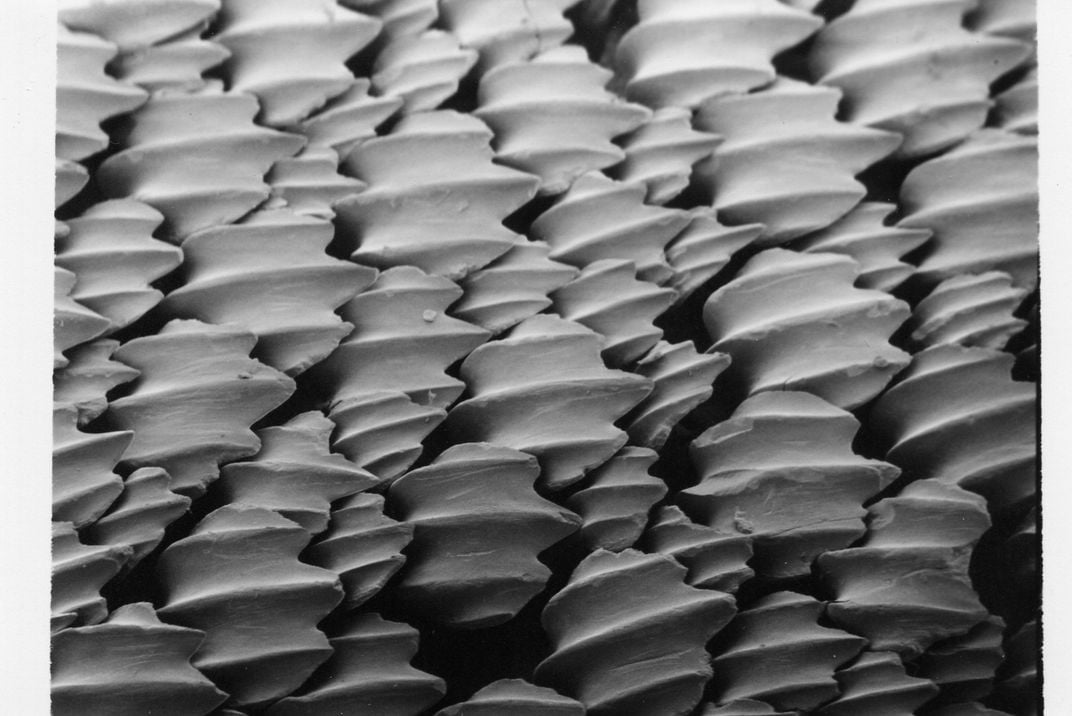

Sleek, muscular, and highly efficient swimmers, it’s no wonder that sharks provided the inspiration for GM’s 1961 Chevrolet Corvette Mako Shark concept car. But sharks owe their prodigious swimming talents to more than their shape, and their lesser-known qualities have also inspired human invention. Shark skin, for instance, consists of a mosaic of tooth-shaped scales called denticles, which inspired Speedo’s Fastskin II that made headlines during the 2008 Olympics. Replicating the drag-reducing properties of the denticles in fabric has proven challenging, but current research using 3D printing technology is showing promise in other materials. Companies are implementing the ridged surfaces to increase aerodynamic efficiency in products ranging from wind turbines to boats and planes.

Think the graceful undulations of a swimming shark look cool? So did researchers at BioPower Systems, who recently developed an energy-harvesting device that converts tidal movements to power. Shaped like a shark fin that oscillates from side to side in an incoming tide, the device converts that movement into usable energy. A shark’s keen sense of smell also has technological applications: Researchers at Mote Marine Laboratory Center for Shark Research and Boston University are applying a sharks “smelling in stereo” method to robotics sensors. A shark’s nostrils are spatially separated on opposite sides of their head causing scents to be perceived at different times in relation to the direction and source of the smell. Robotic applications include the detection of an underwater chemical spill or oil leak source.

Scientists are also looking to some of sharks’ weirder and lesser-known qualities in a bid to replicate some of nature’s solutions—part of a burgeoning field called biomimicry. One is shark jelly: scientists have known since the 1960s that sharks can detect their prey with electrical sensors called ampullae of Lorenzini, named after the man who discovered them in 1679. The tubular pores that dot the faces of sharks and rays detect electrical impulses created by muscle contractions, like that of a fish’s heartbeat. Scientists recently determined that the mechanism of detection lies in a jelly-like substance within the ampullae that acts as a highly efficient proton conductor—basically a high-speed railway for electricity. The jelly could help us build new types of electrical sensors that might lead to more efficient fuel cells, a promising renewable energy source.

Even as we study sharks themselves, many human innovations have stemmed from our efforts to get away from them. Patterned wetsuits and surfboards designed to minimize unwanted encounters with sharks rely on the fact that sharks use visual cues from silhouettes of their favorite prey—seals and turtles—to make decisions on when to take a bite. Researchers are also developing a technology called Clever Buoy, which combines shark-detecting sonar software with satellite communications to create a shark warning system for beaches with active swimmers. When a shark swims by the submerged sensor, a sonar image is recognized by the computer and then a message is sent to beachgoers via lifeguards on the shore. (Too bad they didn’t have one of those in Jaws!)

Health

People once thought sharks were immune to cancer, a long-standing myth that gave rise to a proliferation of pricey shark cartilage supplements. This myth was based on the fact that sharks have flexible cartilage skeletons instead of bones: scientists were excited by early research indicating that cartilage acts to suppress the formation of new blood vessels, a necessity for growing tumors. Unfortunately, studies have since shown sharks do in fact get cancer, and anyways, the expensive cartilage obtained from sharks is actually too large to be effectively absorbed by the human digestive system.

Yet sharks may still hold medical secrets. Dr. Michael Zaslov from Georgetown University found that shark livers contain the unique compound squalamine, an integral part of a shark’s immune system that could provide clues to new antiviral treatments. Squalamine differs from standard antivirals in that it increases the host cell’s capabilities of fighting infection rather than targeting a specific virus. The compound is shark-friendly as well: scientists have been able to synthesize the compound in a lab since 1995. Squalamine is a promising new discovery, considering the rapid adaptation and resistance to drugs in viruses like influenza, and could be used in future vaccines.

Sharks also have antibacterial properties. The same denticles that reduce drag while sharks swim also act as a natural microbial deterrent. Researchers have adapted this technique to make ridged surfaces for submarine and ship hulls in order to deter algae growth. Hospitals, too, now model their countertops and surfaces after shark skin in an effort to decrease the spread of infectious disease.

Entertainment

Long before Jaws, native Hawaiians took shark attacks as amusement to an extreme level. To appease the shark gods, they built gladiator-style shark pens where selected athletes were matched against an adversary shark. Think Spanish bullfights: armed with a single shark-tooth dagger, the shark warrior was offered one chance to defend himself against a charging shark. Most often the shark emerged victorious. A few athletes said to possess “akua,” or magic, however, succeeded in killing their opponents and escaped the sacrificial death.

In 1975, Jaws shocked moviegoers for its visually realistic portrayal of a rogue shark attacking beachgoers, and swiftly became a blockbuster classic. Today we continue to enjoy the thrill of watching sharks onscreen. This summer’s shark thriller is The Shallows , but other favorites that have hit the big screen include Sharknado and the annual summer television event Shark Week that has aired for the past 29 years. (Keep in mind many of the hunting behaviors portrayed in the movies are fictional, so don’t let these images stop you from enjoying your beach vacation planned for the summer.)

Increasingly, however, the emotional bond between people and sharks has moved into more positive territory. Lydia the Shark, the first great white to be recorded crossing the Atlantic, has more than 26,000 Twitter followers, and a dancer dressed in a shark costume managed to upstage Katy Perry during a Superbowl halftime show. Peaceful shark-watching has become big business around the world, even on Martha’s Vineyard where Jaws was filmed. Last summer beachgoers on nearby Cape Cod successfully rescued a beached great white shark, which serves as a heartwarming story about the ability for sharks and humans to coexist.

Learn more about the seas with the Smithsonian Ocean Portal.

Learn more about the seas with the Smithsonian Ocean Portal.