New Web Tool Helps Avoid Flooding by Finding the Best Spots to Build Wetlands

Specifically placed small wetlands can help capture watershed runoff, helping city planners to guard against flood disasters

![]()

Wetlands, such as this marsh above, buffer communities against flooding. Photo by Flickr user daryl_mitchell

In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy last fall, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo joked to President Barack Obama that New York “has a 100-year flood every two years now.” On the heels of flooding from 2011′s Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee, it certainly seemed that way. Given that climate change has sparked multiple major storms and raised sea levels, and that urban and agricultural development have impeded our natural flood-management systems, chronic flooding could be here to stay.

Wetlands, which include swamps, lagoons, marshes and mangroves, help mitigate the problem by trapping floodwaters. “Historically, wetlands in Indiana and other Midwestern states were great at intercepting large runoff events and slowing down the flows,” environmental engineer Meghna Babbar-Sebens of Oregon State University said in a recent statement. ”With increases in runoff, what was once thought to be a 100-year flood event is now happening more often.”

One key problem is that most of our wetlands no longer exist. By the time the North American Wetlands Conservation Act (PDF) was passed in 1989, more than half of the wetlands in the United States had been paved over or filled in. In some states, the losses are much greater: California has lost 91 percent of its wetlands, and Indiana, 85 percent. In recent years, scientists have been honing the art of wetlands restoration, and now a recent study published in the journal Ecological Engineering by scientists at Oregon State University is helping to make new wetlands easier to plan and design.

Scientists are using an Indiana watershed to study how wetlands can be created or restored to help stem the effects of climate change. Photo by Flickr user Davitydave

The research focused on Eagle Creek Watershed, ten miles north of Indianapolis, and identified nearly 3,000 potential sites where wetlands could be restored or created to capture runoff. Through modeling, the scientists discovered that a little wetland goes a long way. “These potential wetlands cover only 1.5% of the entire watershed area, but capture runoff from 29% (almost a third) of the watershed area,” the study authors wrote.

Their next step was to begin developing a web-based design system to allow farmers, agencies and others to identify areas optimal for new or restored wetlands and to collaborate in designing them. The recently launched system, called Wrestore, uses Eagle Creek as a test-piece.

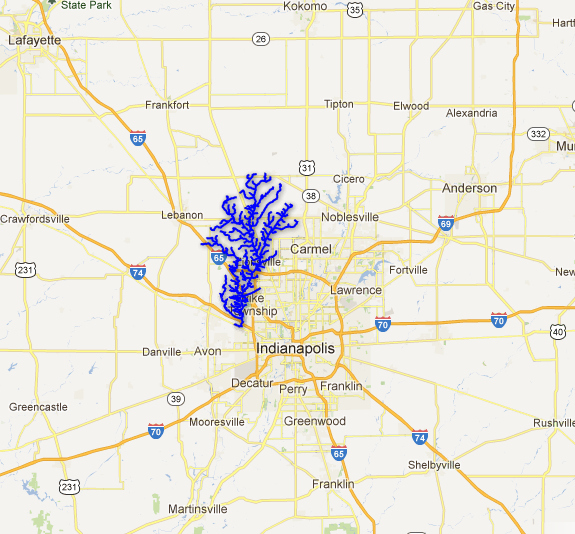

A new web tool analyzes different components of a watershed; Indiana’s Eagle Creek Watershed steam network is pictured here. Map courtesy of Wrestore

The tool has a variety of functions: It helps identify a region’s rivers and streams, divides watersheds into smaller sub-watersheds and shows where runoff is likely to collect—places conducive to building wetlands. If a city wants to reduce flooding in its watershed, the site’s interactive visualization engine displays various conservation options and allows groups of city planners to collaborate on the design of new wetlands.

“Users can look at various scenarios of implementing practices in their fields or watershed, test their effectiveness via the underlying hydrologic and water quality models, and then give feedback to an ‘interactive optimization’ tool for creating better designs,” Babbar-Sebens, lead author of the study and the lead scientist on the web tool, told Surprising Science.

It provides an easy way for landowners to tackle such environmental challenges. “The reason we used a web-based design system is because it gives people the flexibility to try and solve their problems of flooding or water quality from their homes,” Babbar-Sebens said.

As the spring flood season approaches and environmental degradation continues throughout the nation, a new tool for mitigating wetland loss with targeted, minimal wetland gain is certainly a timely innovation. Babbar-Sebens and her team have been testing it out on Eagle Creek Watershed and will be fine-tuning it throughout the spring. ”There is a lot of interest in the watershed community for something like this,” she said.