How Can Viruses Like Zika Cause Birth Defects?

While the link between Zika and microcephaly is uncertain, similar diseases show how the virus might be affecting infants

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/be/9fbe28de-8316-44a9-8fad-bbb197f20499/42-81618124.jpg)

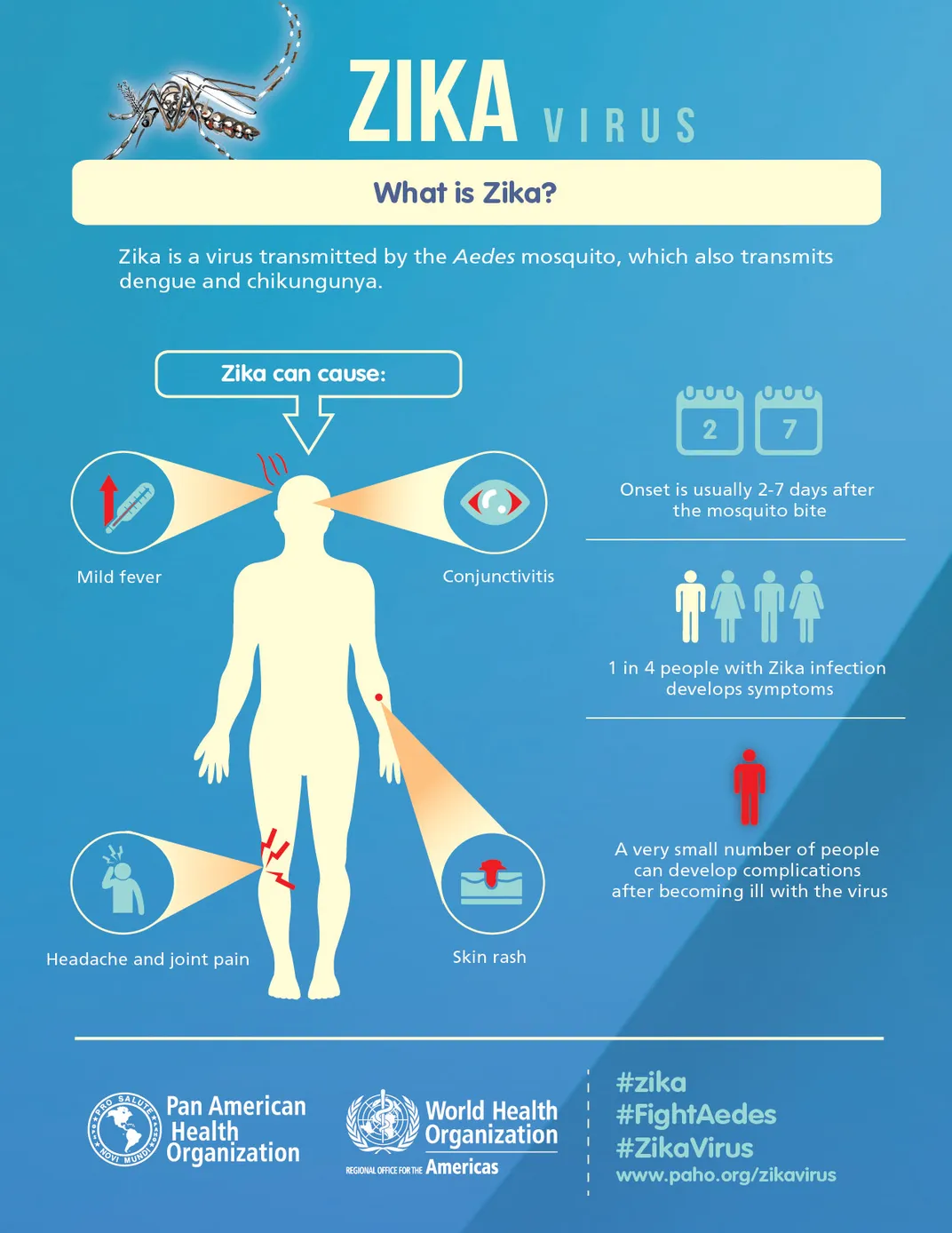

In adults, the symptoms of the Zika virus are relatively mild—rashes, fever, joint pain, malaise. Most who are infected may not even know it. But as this seemingly routine disease spreads across the Americas, so do cases of a much more severe problem: infants born with microcephaly.

This birth defect comes from malformation of the brain, leaving those inflicted with varying degrees of shrunken heads and in many cases a slew of neurologic problems. These include hearing troubles, developmental delays and intellectual impairment.

Brazil usually sees a couple hundred cases of microcephaly per year—a number that some suggest is unusually low due to underreporting. Diseases from parasites like malaria or toxoplasmosis, genetic mutations and even excessive alcohol consumption during early pregnancy can all cause microcephaly. But since October 2015, well over 3,500 infants have been reported with telltale signs of the deformation, coinciding with the explosive spread of the Zika virus in the region.

The spotty information from this outbreak is not enough to definitively say whether Zika causes microcephaly. But the link is plausible, and medical experts are looking to other viruses known to cause developmental defects to try to figure out Zika’s potential pathway to destruction.

“Certain viruses really love the brain,” says Kristina Adams Waldorf, an obstetrics and gynecology doctor who studies how infection induces preterm labor. Cytomegalovirus and rubella have relatively mild impacts on healthy adults but can cause debilitating birth defects. And varicella-zoster virus (which causes chicken pox) can cause a host of complications, including problems in the brain.

Many mosquito-borne viruses, like West Nile, also cause forms of brain injury in adults. “So it’s not a big stretch for us to make the connection between a mosquito-born virus [and] microcephaly,” she says.

Spread mainly by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, Zika was first identified in Uganda in 1947 in rhesus monkeys. Notable outbreaks struck humans on the tiny island of Yap in 2007 and in French Polynesia in 2013. But few people in the Americas had likely heard of Zika until the recent outbreak exploded in Brazil.

No one knows how the virus got there, but many have suggested that it arrived in 2014, carried in the blood of someone among the hordes of people flocking to the World Cup. Since then Zika has spread to more than 20 countries and territories. The possible link to microcephaly has sparked travel warnings for pregnant women and prompted the World Health Organization to declare Zika a global health emergency.

It’s no medical surprise that a virus like Zika can have relatively mild impacts on adults but potentially catastrophic effects on developing fetuses.

Viruses reproduce by hijacking their host’s cells, using their natural processes to make copies of themselves. These copies then strike out on their own to infect more cells. When a virus interferes, the cells can’t function normally—the virus either kills the cells or prevents them from functioning well enough to report for duty. That makes viral infections especially dangerous for developing babies.

“When the fetus is developing its brains, there are a lot of sensitive cells there that have to get to the right places at the right times,” says virologist Kristen Bernard at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. That’s a serious problem in fetuses, which don’t yet have robust ways to fight off microbial invaders.

“You’re talking about a fetus that has a minimal immune system, whereas an adult has, hopefully, a fully functioning immune system,” explains pediatrician and immunologist Sallie Permar of the Duke University School of Medicine.

This cellular vulnerability is the basis of developmental issues linked to cytomegalovirus, or CMV, says Permar. CMV is in the Herpes family of viruses and is the most common infection passed from mother to child in the United States. Between 50 and 80 percent of people in the U.S. will be infected with the virus by the age of 40, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Similar to Zika, few of these people will ever show symptoms of the infection.

We don’t have a great understanding of how CMV-infected cell impairment results in specific neurologic defects in babies, Permar says, but there are clues. “It seems that where the virus is replicating is where you end up with some neurologic impairments.”

For example, hearing loss is a major problem for infants born with CMV. In such cases, the virus can be found in both the part of the brain that helps with hearing as well as a portion of the inner ear called the cochlea, Permar says.

Similarly, some genetic cases of microcephaly have previously been linked to the dysfunction of a particular structure in cells called a centrosome, says Adams Waldorf. This structure is where the “scaffolding system” of the cell organizes and is involved in cell replication, she explains. When the centrosome is damaged, the brains don't develop properly.

It’s possible Zika is staging an attack on infant brain cells that mirrors the genetic condition. In December, the Brazil Ministry of Health announced identification of Zika virus in multiple tissues of an infant with microcephaly, including the brain. But it’s still too early to make a direct link.

It’s also unclear how Zika can penetrate the natural barrier between mom’s bloodstream and her placenta—although there’s already evidence that it can happen. In the same report, the Brazil Ministry of Health also confirmed two instances of Zika in the amniotic fluid of developing fetuses with microcephaly.

No matter the virus, if mom gets a severe illness during pregnancy, additional damage can be caused by the so-called “bystander effect,” says placental biologist Ted Golos of the University of Madison-Wisconsin.

When the body detects something foreign, like a virus or parasite, it triggers inflammation in an attempt to get rid of the intruder. Despite these positive intentions, “the cascade of events that happen in response to a pathogen can [poorly impact the fetus] in a collateral damage kind of way,” he says. Inflammation of the placenta, for instance, can cause miscarriages and other complications.

There’s added concern that if the link between Zika and birth defects is confirmed, many of the longer term impacts of this disease won’t be identified for years. “Microcephaly is a tragic outcome,” says Golos. “But it could very well be the tip of the iceberg. Or it might not … we simply don’t know.”

The hope now is that researchers can develop a Zika vaccine, so if the virus is causing birth defects, we can stamp out their cause.

“We have the tools to eliminate one very severe congenital infection, and that’s been rubella virus,” says Permar. “So there is a success story with a maternal vaccine.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)