Bulldogs Are Dangerously Unhealthy, But There May Not Be Enough Diversity in Their Genes to Save Them

How we loved this dog into a genetic bind

:focal(274x157:275x158)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/15/ca15e676-bfa1-4180-ae4b-02797b55c093/gettyimages-511711532_720.jpg)

Uga, the beloved canine mascot of the University of Georgia’s sports teams, wouldn’t be much on the field. With his squashed, baby-like face and stout, low-slung torso, he looks more likely to take a nap than make a tackle. Yet it is because of these very features—not in spite of them—that the bulldog has won hearts on both sides of the Atlantic, rising to the heights of university mascot and even proud icon of the U.S. Marine Corps.

And it is because of the bulldog’s legions of admirers—not in spite of them—that the breed is now in trouble. Decades of breeding have accentuated the traits that make up the dog's distinctive and wildly popular look, but compromised its health in the process. Now, the first comprehensive genetic assessment suggests that the bulldog no longer has the genetic diversity left for breeders to raise enough healthy animals to improve its overall outlook.

“They've lost so much genetic diversity over the past decades,” says Niels Pedersen, professor emeritus of medicine and epidemiology at the University of California at Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and lead author of the new assessment. “It's a breed that's really kind of bred itself into a genetic corner.”

The study, published Thursday in the open access journal Canine Genetics and Epidemiology, represents the first broad-based effort to assess genetic diversity among English bulldogs using DNA analysis. Pedersen and colleagues tested 102 registered English bulldogs used for breeding, 87 from the United States and 15 from overseas. They compared that group with a second subset of 37 English bulldogs that had been brought to the university's Veterinary Clinical Services for various health problems.

For bully-lovers, the results are harrowing: Researchers found that little wiggle room remains in the bulldogs' limited genes for breeders to rebuild healthy phenotypes from within the existing breed. Introducing new genes from outside the purebred bulldog line could be a boon to the animals' health. But because the resulting dogs are no longer pedigreed and don't look exactly like today's standard, diehard bulldog breeders aren't likely to start that process anytime soon.

Boasting both looks and personality, the bulldog has long been among the most popular dog breeds in the U.S. and UK. The American Kennel Club describes them as “equable and kind, resolute and courageous." As Pedersen puts it: "The bulldog's saving grace is that people absolutely love them and are willing to overlook all their health problems. They're an ideal pet, relatively small but not that small, they don't bark a lot, they aren't that active, and they are really placid and they have a beautiful disposition.”

But his research suggests that all that love might not be enough to save them. In fact, love itself is the problem.

It's well known that bulldogs suffer from a variety of physical ailments that make them particularly unhealthy—and that many are the unfortunate byproducts of breeding to the extremes of the same physical features that win them prizes and acclaim. As a result, the bulldog's lifespan is relatively short, with most living on average a mere 8 years according to one recent study by the National Institutes of Health.

The bulldog's list of ailments is long. First their thick, low-slung bodies, broad shoulders and narrow hips make bulldogs prone to hip dysplasia and make it difficult for them to get around. Short snouts and compressed skulls cause most to have serious breathing difficulties, which not only increases their risk of respiratory-related death but makes it tough to keep cool. Wrinkly skin can also make bulldogs more prone to eye and ear problems. As if that weren’t enough, the dogs are plagued by allergic reactions and autoimmune disorders exacerbated by inbreeding.

Perhaps the most telling example of how dramatically human breeders have manipulated the bulldog is this: The breed is now largely unable to procreate naturally (even more so than the giant panda, which notoriously requires “panda porn” to be enticed to do the deed in captivity). Bulldogs are often too short and stocky to mate, and their heads as infants are too big for a natural birth from the dog's narrow pelvis. So the breed survives thanks to artificial insemination and cesarian section births, which have become the norm.

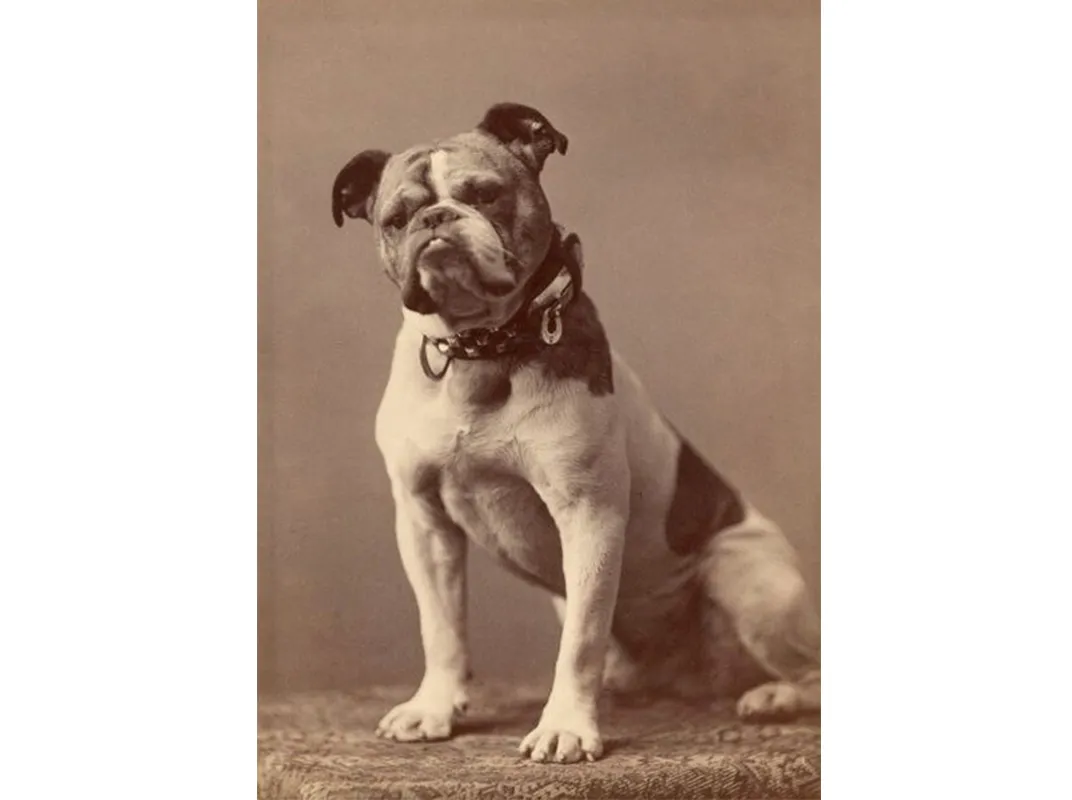

How did the sturdy bulldog, symbol of the British Empire, end up in such a bind? First, you have to understand that today's bulldog is the product of hundreds of years of selective breeding. As recently as the mid-19th century it looked quite different. The bulldog’s ancestors were fighters, bred for bull-baiting before the English banned the sport in 1835. But those taller, leaner, less-wrinkled and far more athletic bulldogs didn’t make great house pets, and so were largely unwanted.

Soon, a handful of breeders who loved the dogs began to reinvent them through selective breeding. By the second half of the 19th century the bulldog had a new look—and a new popularity that criss-crossed the Atlantic ocean. The AKC recognized the modern breed of bulldog in 1886, and the bulldog was chosen to represent such august institutions as Yale University, which appointed the bully "Handsome Dan" as its icon in 1889. But the seeds of the modern bulldog’s genetic demise were sown from the start, Pedersen says.

A very small number of founding dogs—just 68, by Pedersen’s estimates—began the breed. All purebred bulldogs today have descended from those dogs and their progeny. Later, humans created subsequent “bottlenecks” that even further reduced the gene pool of this small group. “Those probably involved a popular sire that everybody loved,” Pedersen explains. “He may have been a show winner, and so everybody then subsequently bred his line.”

In recent decades, the dog’s popularity has spawned inbreeding and rapidly altered the shape and style of its body—as one can see in the various versions of Uga, the University of Georgia mascot. But inbreeding isn’t the primary problem, says Pedersen. It's that such breeding was done to create the distinctive physical attributes that make a bulldog look like a bulldog. Those aesthetic “improvements”—dramatic changes to head shape and size, skeleton, and skin—come with a heavy cost.

“If you look at standard poodles, they're almost as inbred as bulldogs but they are far more healthy because their inbreeding wasn't directed towards drastically changing their appearance,” Pedersen says. “The standard poodle doesn't look too much different than the ancestral village dogs, that are still in the Middle East and other parts of the world."

Many breeders simply deny that the bulldog has any unusual problems. “It is a myth that the Bulldog is inherently unhealthy by virtue of its conformation,” declares the Bulldog Club of America's official statement on the health of the breed. Yet a Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine study that investigated causes of death for more than 70,000 dogs between 1984 and 2004, found that bulldogs were the second most likely breed to die of congenital disease. (Newfoundlands were most likely.)

Breeders often blame health ills on unscrupulous, puppy mill-type breeders who breed sick and otherwise unsuitable dogs indiscriminately. It’s true that the odds of getting a healthier individual bulldog are far better when buyers deal with credible breeders who screen for health issues in advance. But when it comes to the health of the breed as a whole, the genes tell a different story, says Pedersen.

Puppy mill breeders can run down the genetics of a popular breed in a hurry, but that doesn't appear to apply where the bulldog is concerned. “When we analyzed the dogs who came into the clinic for health problems, who tended to be more common or pet store type bulldogs, they were genetically identical to the registered and well-bred dogs,” he says. “The mills aren't producing dogs that are much differently genetically as far as we could see than the ones being bred properly.”

Understanding genetic diversity is crucial to managing the future of any breed, says Aimée Llewellyn-Zaidi, head of health and research at the Kennel Club (Britain's counterpart to the AKC). Her organization has participated in genetic research, including providing canine subjects for a 2015 genetic study published in Canine Genetics and Epidemiology that estimated the rate of loss of genetic diversity within pedigreed dogs. That study found that bulldogs might enjoy some modest replenishment of genetic diversity through the use of imported animals, which could be an avenue to improve bulldog genetics.

“It would be very interesting to use genomic tools to investigate the bulldog breed on a global level, as it is well-established that breeds that have developed in isolation over time can be utilized to improve over-all genetic diversity and selection for positive characteristics, on a global level,” says Llewellyn-Zaidi, who was not involved in the research.

Some breeders are already taking steps to improve the lovable dog's lot. In 2009, the Kennel Club altered the regulations for bulldogs to discourage breeding for the purpose of exaggerating features like short muzzles or loose skin that humans find desirable but have detrimental impacts on dog health. That means leaner bulldogs, and less wrinkly ones so that eyes and noses are not obscured. Others are creating non-pedigreed, mixed bulldog breeds like the Olde English Bulldogge and the Continental Bulldog, which look more like throwbacks to the bulldog's more athletic ancestors.

If such hybrid breeds catch on, the bulldog's future might look a bit more like its past—and certainly a lot brighter. But that will only happen if more breeders decide to embrace something a bit different from the dogs they now know and love.