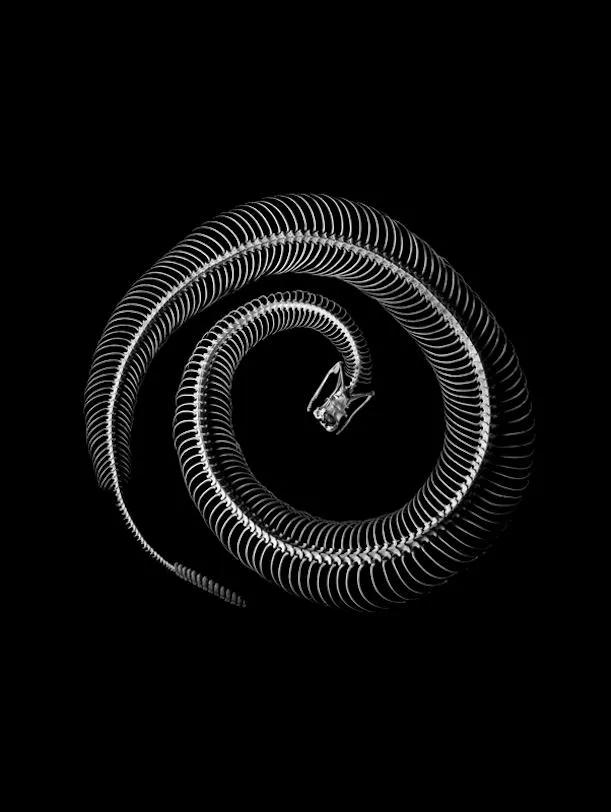

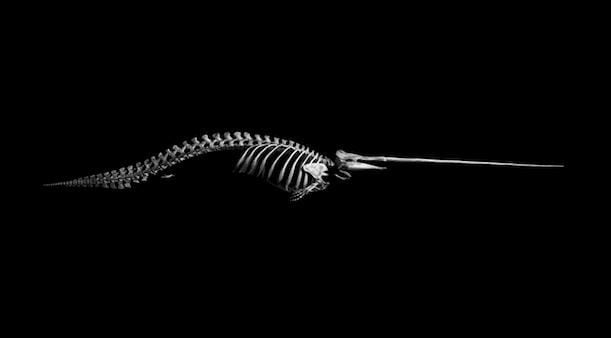

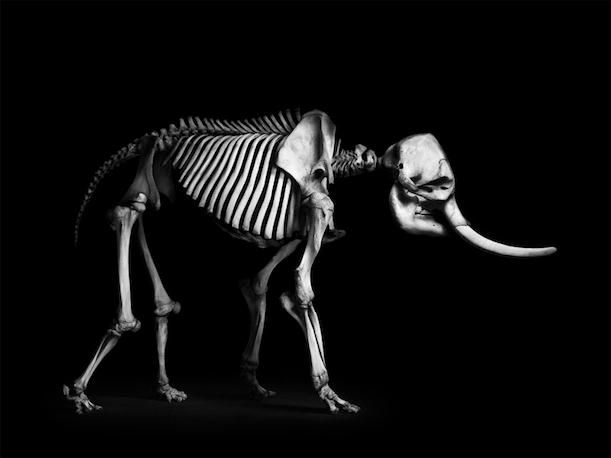

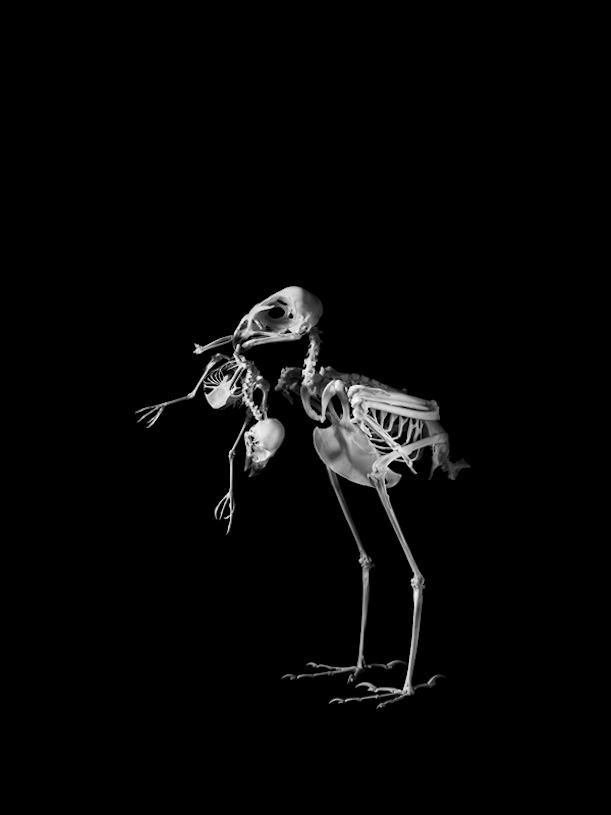

Beautiful Anatomical Skeletons, Posed and Photographed As Sculptures

Photographer Patrick Gries transforms ordinary specimens, stripped of fur and flesh, into art that showcases motion, predation and evolution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/22/3b22bb55-d3c4-4e9d-83ca-c1416f9b3873/rabbit-and-golden-eagle.jpg)

What happens when you unleash an acclaimed luxury goods photographer on hundreds of anatomical animal skeletons kept in museum collections?

If that photographer is Patrick Gries and the skeletons are those of Paris' Natural Museum of History, you'll get a series of 300 stark photographs that transform staid, ordinary scientific specimens into biological art.

Gries shot these images to accompany text by oceanographer and documentarian Jean-Baptiste de Panafieu in the book Evolution, published by Xavier Barral, and they were recently featured in the Photovisa festival in Krasnodar, Russia.

"If you go to the museum, you'll see thousands of skeletons," Gries says. "My job was to take one specimen, isolate it, and work with light to photograph that specimen as if it was a sculpture."

De Panafieu's essays tell the story of evolution piece by piece—with chapters on adaptation, convergence, homology and other broad themes—while Gries' striking photos isolate the essence of each animal's unique adaptations.

Simultaneously, though, the photos highlight the common anatomical characteristics shared by all vertebrates. Stripped of fur and flesh, it can be hard to identify the skeletons without a label: without ears, a rabbit doesn't look all that different than a cheetah, and a monkey's skull differs only in scale from a human's.

Creating the seemingly simple images was far harder than it might appear, Gries says. The photos were taken over the course of six months, with animals selected largely by de Panafieu so that Gries could illustrate his essays. Most were from the Paris museum, but the duo also visited four other museum collections in France to obtain access to the skeletons they wanted.

Although the skeletons may appear to hover in a pristine state in midair, that illusion is the result of both digital and real-world ingenuity by Gries.

"It was very difficult working in the museums," he says. "Many of the skeletons' feet are nailed to wooden boards, and we couldn't touch anything, so we had to remove these things by computer."

Making the animals appear as though they were moving, as de Panafieu wanted for the book, was also rather tricky. "You have to realize that with the skeletons, nothing moves. Some of them look like they're in action, but everything is pretty stiff," Gries says. "So we had to use nails and wires to hold them in place."

"When you look at the pictures, it looks high tech, but the way we had to do it was quite low tech," he says.

"What I like about it is that you wouldn't even realize it," Gries says. "You'd look at the pictures and think they're just the way the skeletons are presented, not wondering, 'where are the nails and the wires?'"

The photos that include multiple animal skeletons, which illustrate concepts like predation or evolutionary arms races, are largely composed of pairs of animals that are featured together in the actual museum exhibits.

"What's most interesting to me is the cross between art and science. I love working on projects where I can cross disciplines," Gries says.

Although projects that encompass both art and science aren't radical ideas in the U.S. and in many other countries, Gries notes that there's still resistance to combining the two in France.

"I think that's starting to change, though, and I'm glad," he says. "I'm not a scientist, but I learned so much during this project, due to the chance I had to work with one."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)