There’s a New Job in the Solar Industry

And it involves shepherding a landscaping crew of hungry sheep

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/68/4368f89a-1c80-4b5d-bc9d-03babcc441cc/sheep-on-solar-farm.jpg)

On the east side of Kauai, a herd of sheep grazes in an unusual pasture. The low valley, flanked on either side by green mountains, is the site of a 13-megawatt solar farm, where some 300 hungry sheep prune the grasses that grow around 55,000 solar panels.

While this may seem like a surprising collaboration, it is a trend that has grown with the rise of utility scale solar development in agricultural areas across the country. Large solar installations are often found in rural areas, and many times, there are local farmers that raise animals nearby. One of the biggest and most expensive operational challenges solar farms face is controlling vegetation on the sites. Overgrown plants can create unwanted shade, compromising electricity production, or even become tangled in the wiring on the backside of the arrays.

A spokesperson for Duke Energy, one of the largest electric power holding companies in the United States, says, “Other than the lease of the land, vegetation management is the number one expense at our solar facilities.”

While mowing has historically been the go-to method for vegetation management, in recent years, grazing sheep have become another landscaping solution, and one that can be a win-win for the energy and agricultural industries.

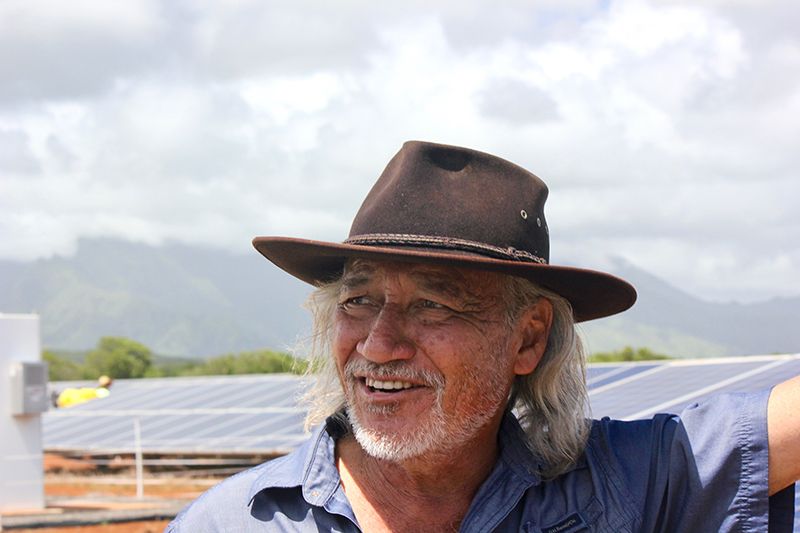

The shepherd at the Kauai solar farm in Lihue, Daryl Kaneshiro, is a retired petrol worker and former Kauai council member. Kaneshiro grew up on the west side of the island, and ranching has been a part of his life for as long as he can remember. He grew up on his family’s poultry farm, and in 1998, began running cattle and sheep on his own 300 acres, now Omao Ranch Lands. In 2013, the solar developer MP2 leased a portion of his land to install a small 250-kilowatt solar array, and Kaneshiro was hired to maintain the grounds.

Kaneshiro first mowed and did weed whacking and other maintenance by hand. Then, in an effort to cut down on the manual maintenance, he tried fencing in sheep and moving them in rotations to strategically eat the vegetation. He now has close to 700 sheep in his herd and maintains three farms on the island. Kaneshiro serves as an agricultural consultant for a fourth, an AES solar and battery site, which is expected to become operational in late 2018. Grazing sheep on solar farms has become the primary source of revenue for his family, enabling them to continue to build the ranch, install a solar-powered aquaponics system, and lay the groundwork for a farm-to-table restaurant at the ranch.

This is not the only place where the energy and agricultural sectors have come together. While it is fairly uncommon for farmers to both receive land lease payments and secure the maintenance contract for a site, as Kaneshiro has, the solar and agricultural industries have been blooming side by side. Sheep have been seen grazing solar land from coast to coast, in Hawaii, California, Texas, New Jersey and New York. The partnership is particularly strong where utility scale solar—large farms usually over 20 acres—has been established.

The solar shepherd phenomenon is perhaps most notable in North Carolina, which has become a national hotbed for utility scale solar, ranking second in the country to California with over 3,700 megawatts of solar installed in nearly 7,000 installations. Companies such as Apple, Ikea, Corning and Dow have all developed solar farms in the state. With the explosion of solar farms comes a need for grounds maintenance.

Tonje Woxman Olsen co-founded Sun Raised Farms in 2012 to serve as a maintenance contractor for solar farms specifically. The company offers mowing, grazing and agricultural services, and manages a network of sheep farmers throughout the state that want to grow their flocks and serve these solar sites. (Given that each solar farm is built differently, with varied geographies, soil baselines, sizes and designs, some areas of the pasture might be better maintained by mowing than grazing, or vice versa.) Sun Raised Farms recently expanded outside of North Carolina, securing a contract for a 20-acre solar farm in Virginia. The company sees the benefit to local farmers as twofold: a place for them to graze sheep, which can then be sold for lamb, strengthening the domestic, pasture-raised lamb market, and direct income from the solar farm owners for performing quality maintenance services. The outfit now grazes sheep on 1,000 acres of solar pasture, which totals 250 megawatts of solar capacity.

A primary benefit to the solar shepherds is income diversification.

Shawn Hatley, owner of Blake’s Creek Ranch and The Naked Pig Meat Co. located in Oakboro, North Carolina is a member of the Sun Raised Farms network. He speaks about the importance of having multiple revenue sources in the agricultural industry today. According to a 2017 USDA report, 50 percent of farms in the United States generate less than $10,000 annually in sales. And 80 percent of farms make less than $100,000 each year in sales.

“The more enterprising, the more economically resilient a business is,” he says. “Historically, you could raise a family of four on a 100-acre farm with carpentry, crop, egg and cattle sales. On today's farms, farmers may have crop rotation, but for our scale, farms need to have multiple enterprises to compete with large agricultural operations.”

The College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at North Carolina State University began integrating solar shepherding into its agricultural seminars in September 2016. Interest is growing and the university is now considering creating programs that focus exclusively on sheep grazing for solar farms.

Hatley sees his sheep as another crop, and the decision to raise sheep requires a significant investment, just as a new crop would. It could be up $500,000 to grow a flock of 1,000 ewes, between the initial capital investment and operational overhead over five years. But it is also another revenue stream. If all goes as planned, the grazing operation will be a means to make his business more resilient to the uncertainties of agricultural life: fluctuating commodity prices, input costs, crop output and extreme weather.

Solar shepherding is a real opportunity, Hatley thinks, when the ultimate goal is to make farming work financially.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Headshot_MollyASeltzer.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Headshot_MollyASeltzer.jpg)