Why Marquis de Lafayette Is Still America’s Best Friend

A conversation with Sarah Vowell about her new book, the American Revolution and what we can learn from the Founding Fathers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/30/ee3065c3-6b03-4229-9f69-82a6e2aa0b2a/gilbert_du_motier_marquis_de_lafayette_-_high_res.jpg)

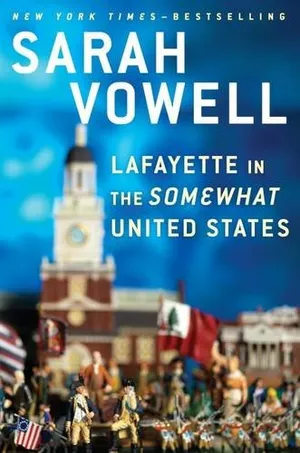

In her new book, Lafayette in the Somewhat United States, writer Sarah Vowell tells the story of the American Revolution through the life and experiences of Marquis de Lafayette, the French aristocrat who joined the Continental Army as a teenager, convinced King Louis XVI to ally with the rebels, and became a close friend of George Washington.

Lafayette symbolizes many things for Vowell: the ideals of democratic government, the hard reality of those democracies, the tremendous debt early Americans owed to France and the importance of friendship. Like her previous books, such as Assassination Vacation, Lafayette strikes witty blows against the stodgy sorts of U.S. history taught in classrooms. It's less a history book than a collection of stories. I spoke with her last week about her work, her opinion of Lafayette, why she doesn't consider herself a historian, and what she admires about the hit Broadway musical Hamilton.

The interview was edited and condensed.

Why did you decide to write a book about Marquis de Lafayette?

That question always stumps me. There are so many answers to that. I lived near Union Square in New York City for about 10 years. There's a statue of Lafayette in the square and it's right next to the sidewalk, so I walked by him pretty much every day. He was one of my neighbors so I was always thinking about him. And also, I had written a shorter piece a number of years ago about Lafeyette's return trip to America in 1824

Was that the story that appeared on This American Life?

Yes, yeah. It was for a show about reunions and that piece was a very kind of sentimental journey, literally, about how he came back in 1824. He was invited by President Monroe, he stays for over a year and the whole country goes berserk for him. It's just Lafayette mania. Two-thirds of the population of New York City meets his ship. Every night is a party in his honor. And I guess the reason that story attracted me was because of the consensus that the whole country embraced him. By 1824, the Civil War is pretty much a foregone conclusion. But because he was a Frenchman and because he was the last living general from Washington's army, the whole country—north and south, left and right—he belonged to everyone and that seemed so exotic to me.

So Lafeyette comes back to America in 1824, just shy of 50 years after the revolution. Eighty thousand people meet him at New York Harbor. It's an enormous crowd.

Totally. Yes. Only 4,000 met The Beatles in 1964.

So why was Lafayette universally beloved when he returned?

I think there are a few reasons. He is, basically, the most obvious personification of America's alliance with France in the war. And Americans back then were still grateful for French money and gunpowder and soldiers and sailors. The help from the French government was the deciding factor in the revolution. Lafayette was the most swashbuckling symbol of that. There was also, then and now, a great reverence and almost a religious love for George Washington. Lafayette had served with Washington and became his de facto adopted son—Lafayette was an orphan and Washington had no biological children of his own—so their relationship was very close. And so, he was so identified with Washington.

The visit also coincided with the presidential election of 1824, which is basically the first election when Americans had to vote for a non-founding father. There was this nostalgia, this kind of national moment of reflection about how the country had to continue on without its fathers. Lafeyette's secretary kept a diary during that whole trip. He marveled that these newspapers would be full of bile about presidential candidates, then Lafayette would show up, and the day's paper would be all like, "We 'heart' Lafayette." Those two things are related a little bit, nostalgia and reverence for that very singular past and nervousness about the future.

And what happened? Why don't we feel that way anymore?

Well, he has been a little bit forgotten, but I think you could say that about many, many figures in American history. I think the forgetting of Lafayette is just a symptom of the larger cultural amnesia. When I was starting my research on this book, there was this survey done by the American Revolution Center that said most adult Americans they didn't know what century the Revolution was fought in. They thought the Civil War came first. They didn't know the Bill of Rights was part of the Constitution. So yes, Lafayette is a little bit forgotten, but so are a lot of other things more important than him.

You mention in the book this idea that Lafeyette is no longer a person. His name is a bunch of places now.

The most practical effect of his visit in the 1820s was that everything started getting named after him. When I was at Valley Forge, I was with this friend of mine who had lived in Brooklyn. There was a monument to the generals who had been at Valley Forge: Lafayette was one of them, and General Greene and DeKalb. And I remember my friend just calling it "that big monument thing with all the Brooklyn streets." A lot of these people just become street names. It's natural that these people leave behind their names and their stories are forgotten, I suppose. But for me, every time I would walk, say, past the statue of Lafayette down towards Gansevoort Street, the whole city came alive. If there's any practical effect of learning about this stuff, it just makes the world more alive and interesting. And it certainly makes walking around certain cities on the eastern seaboard more fascinating.

Let's rewind five decades. Lafayette crosses the Atlantic in 1777, at age 17. He abandons his pregnant wife—

That was unfortunate.

He leaves behind a comfortable aristocratic life. His family doesn't even know what he's doing and it's all to fight in someone else's war.

Right.

Why?

When you put it like that it does not seem like a good idea.

Plenty of 19-year-olds have bad ideas.

Oh, for sure. I would distrust one who only made good decisions. There are a few reasons for his decision to fight. Lafayette married quite young. He's a teenager. He's the richest orphan in France, and he's kind of pounced upon by this very rich and powerful family, then he marries their daughter. His father-in-law wants him to get a cushy boring job at the French court and be a proper gentleman, but Lafayette is the descendant of soldiers. His ancestors are soldiers going back to the Middle Ages. One of his ancestors fought with Joan of Arc. His father, who died when Lafayette was almost two years old, was killed by the British in battle during in the Seven Years War.

There's a grudge there.

That's one reason he's pretty gung ho to fight the British in America. He wants to be a soldier like his father before him and all the fathers before that. He's just one of many European soldiers who flocked to the American theater of war to volunteer with the rebels, some of them not for particularly idealistic reasons, but because they were out of a job. The defense industry in Europe was downsizing. Lafayette is one of these Frenchmen who are coming over to fight.

The other thing is, he got bitten by the Enlightenment bug and was enamored with ideals about liberty and equality. The letters he writes to his poor, knocked-up wife while he's crossing the ocean are incredibly idealistic. He says that the happiness of America will be bound up with the happiness of mankind, and then we'll establish a republic of virtue and honesty and tolerance and justice. He's laying it on a little bit thick because he has just abandoned her. But it's still very stirring, and I do think he believed it.

So after all of your research, after writing this book, spending a lot of time trying to get into his head, how do you feel about Lafayette? Do you like him?

Do I like him? Yes, I do like him. I am very fond of him. He's a very sentimental person I think part of that was his youth, maybe his being an orphan. Jefferson complained of his canine appetite for affection. Lafayette has this puppy-dog quality.

He was kind of a suck-up.

Yeah, he was. But I like puppy dogs. And when push came to shove, Lafayette got the job done. For all of his French panache, he really did roll up his sleeves and set to work on behalf of the Americans. Maybe it was bound up with his lust for glory.

Washington was constantly dealing with desertion crises. His soldiers are deserting him in droves throughout the whole war. And who can blame them? They're not getting paid. They're not getting fed. There's frequently no water. A lot of them don't have shoes. It's a really crummy job. But then this kid shows up like a football player asking his coach to put him in the game.

In his first battle, the Battle of Brandywine, he's wounded and barely notices because he's so busy trying to rally all the patriot soldiers to stand and fight. He never turns down an assignment. He's always ready to get in the game. And then, when he goes back home to Paris after the war, he's constantly helping the American ministers, Jefferson and Monroe, with boring economic stuff. There's not much glory in that. But Lafayette lobbied to get the whalers of Nantucket a contract to sell their whale oil to the city of Paris. That's real, boring, grownup friendship. And then to thank him, the whole island pooled all their milk and sent him a giant wheel of cheese. What was your question?

Do you like him?

Yes, I do like him. The thing I like about nonfiction is you get to write about people. The older I get, I feel I have more empathy for people's failings because I've had so much more experience with my own. Yes, he was an impetuous person. But generally, I think he was well intentioned. And he also really did believe in these things that I believe in. So, yes. Is he a guy that I want to have a beer with?

Would you?

Yeah, of course. Who wouldn't want to meet him?

In this book, you describe yourself as "a historian adjacent narrative nonfiction wise guy." Self-deprecation aside, how does that—

I don't think of that as self-deprecation. You're thinking of that as self-deprecation in the sense that a proper historian is above me on some hierarchy. I don't think that way at all.

I meant that, in the book, it's played a little bit as a joke. You're teasing yourself, right?

I am, but I'm also teasing Sam Adams, because he says, ["If we do not beat them this fall will not the faithful Historian record it as our own Fault?"] I don't think of myself as an historian and I don't like being called one. And I also don't like being called a humorist. I don't think that's right, partly because my books are full of bummers. I reserve the right to be a total drag. I just consider myself a writer. That's one reason I don't have footnotes. I don't have chapters. I just want to get as far away from the stench of the textbook as I can. I inject myself and my opinions and my personal anecdotes into these things in a way that is not historian-y.

Given how you describe your work, and the empathy you've developed towards peoples' flaws, what can you write about that historians can't?

For one thing, empathy can be really educational. If you're trying to look at something from someone else's point of view, you learn about the situation. You might not agree. But as I go on, I become maybe more objective because of this. Ultimately, there's something shocking about the truth.

I'll give you an example. My last book was about the American takeover of Hawaii in the 19th century. It's the story of how native Hawaiians lost their country. It's a big part of their lives and it's a huge part of their culture. And if you go back to the historical record, there are kind of two narratives. There's the narrative of the missionary boys and their descendants, how these New Englanders took over these islands. Then there's the native version of those events, which is necessarily and understandably upset about all of that.

You're trying to parse complicated histories. There's one line early in the Lafayette book that seems related to this: "In the United States there was no simpler, more agreeable time." Why do you think it's so hard for us to recognize dysfunction within our own history? And where does this temptation to just indulge nostalgia come from?

I don't know. I just loathe that idea of the good old days. Immoral behavior is human nature. So I don't know why there's this human tendency to be nostalgic about the supposedly superior morals of previous generations.

Why is it so difficult to recognize and acknowledge the role that dysfunction has played?

I think it has to do with this country. History is taught not as a series of chronological events, but as adventures in American exceptionalism. When I was growing up, I was taught America never lost a war because "America is God's chosen nation." I started kindergarten the year the helicopters were pulling out of Saigon.

It's funny, one reason why Americans loved Lafayette was because of how much he loved them. In 1824 or 1825, he's speaking before the joint houses of Congress and he says, "America will save the world." What European thinks that? We love to think about ourselves as helpful and good.

As saviors?

Yeah. And sometimes, the historical record doesn't back that up. That's true of every country. But unlike every other country, we have all of these documents that say we're supposed to be better, that say all men are created equal. All of the great accomplishments in American history have this dark backside. I feel very reverential of the Civil Rights Movement. But then you think, well, why was that necessary? Or all of these great amendments we're so proud of. It's like, oh, everyone can vote? I thought we already said that.

So how do you—

Let me say one more thing. You know that scene in Dazed and Confused where the history teacher tells the class that when you're celebrating the Fourth of July, you're celebrating a bunch of like old white guys who didn't want to pay their taxes? I'm not one of those people. I don't think it's all horrors and genocide and injustice. I do think it's still valuable to celebrate those founding ideals. And there are some days that the idea that all men are created equal, that's the only thing I believe in. I think those ideals are still worth getting worked up about.

Just because Jefferson owned slaves, I don't think that completely refutes the Declaration. I think you have to talk about both things. I'm not completely pessimistic about it. That's what I love about nonfiction: if you just keep going back to the truth, it's the most useful and it's the most interesting. I don't want to be a naysayer or a "yaysayer." I want to like say them both together. What would that word be?

Ehhsayer?

Yeah, kind of.

So what's next? Do you have plans for another book?

It's what I do for a living so I would hope so. I have a few ideas floating around but I was actually so late.

With this one?

Yeah. And I still haven't recovered. My books, I think they seem breezy to read. I write them that way purposely. But it's incredibly time consuming to put all that together and edit out the informational clutter. I just hate jargon and pretentious obfuscation. This book, which seems like a nice romp through the Revolutionary War, was actually tedious and life sucking to put together. So, yes, I'll write another book when I get over writing this one.

Have you seen Lin-Manuel Miranda's Hamilton musical [which features a rapping, dancing Marquis de Lafayette]?

I have.

What did you think of it?

I mean, what's not to like?

Well, it's not about Lafayette.

No, it's not about Lafayette. That is my one complaint about Hamilton. It has too much Hamilton sometimes. The thing I loved about it most, honestly, was aesthetic. It so perfectly utilized every aspect of theater. It just milked the meaning out of everything. And the nonstop force of the narrative and the rhythm is so effusive and hilarious. I love how alive it is and how alive the people onstage are.

Daveed Diggs!

Daveed Diggs, yes. Daveed Diggs and his hair. He has so much swagger and joie de vivre. I do love how funny it is. But I also like how it doesn't run away from all of these people and their foibles and how they didn't get along.

What would happen if you and Lin-Manuel Miranda went head-to-head, high school debate style?

I'm glad it's high school debate style and not a rap battle because I'm pretty sure he would kick my ass.

Hamilton versus Lafayette. The battle of American heroes. Who wins?

That's the thing. You don't have to choose. I mean, basically, it's going to be Washington. That's even one of the songs, "It's good to have Washington on your side," I think. They each have their contributions. I mean, probably, ultimately, the banking system is more important day-to-day.

We're lucky we don't have to choose.

It'd be a pretty interesting choice to have to make. But, obviously I hope I never have to debate that guy.

The musical is very concerned with the legacies of historical figures. We talked a bit about this already, the idea of what Lafayette has become. What do you think his legacy is today, aside from the statues and the colleges and the towns? What does he represent?

More than anything, he represents the power and necessity and joys of friendship. I think of him as America's best friend. The lesson of the Revolutionary War in general, and of Lafayette in particular, is the importance of alliance and cooperation. A lot of my book is about how much bickering was going on, but I still call it the "somewhat United States" because the founders were united enough. Britain loses because Britain was alone. America wins because America has France. It's easier to win a war when you're not in it alone. And it's easier to live your life when you're not in it alone.

The friendship among those men is one of their more enduring legacies. It's why we call them, we think of them, we lump them together as "the Founding Fathers." Even though they didn't really get along, and maybe they didn't even like other a lot of the time, but they were in it together.