Synchronized Swimming Has a History That Dates Back to Ancient Rome

Before it reached the Olympics, the sport was a spectacle of the circus and vaudeville

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/a2/6ea2c98f-a0dd-4571-85d9-b76e10b4993b/tumblr_lgkwy4u8ca1qa8pt0o1_1280.jpg)

Most people think of synchronized swimming, which gained Olympic status in 1984, as a newcomer sport that dates back only as far as Esther Williams' midcentury movies. But the aquatic precursors of synchronized swimming are nearly as old as the Olympics themselves.

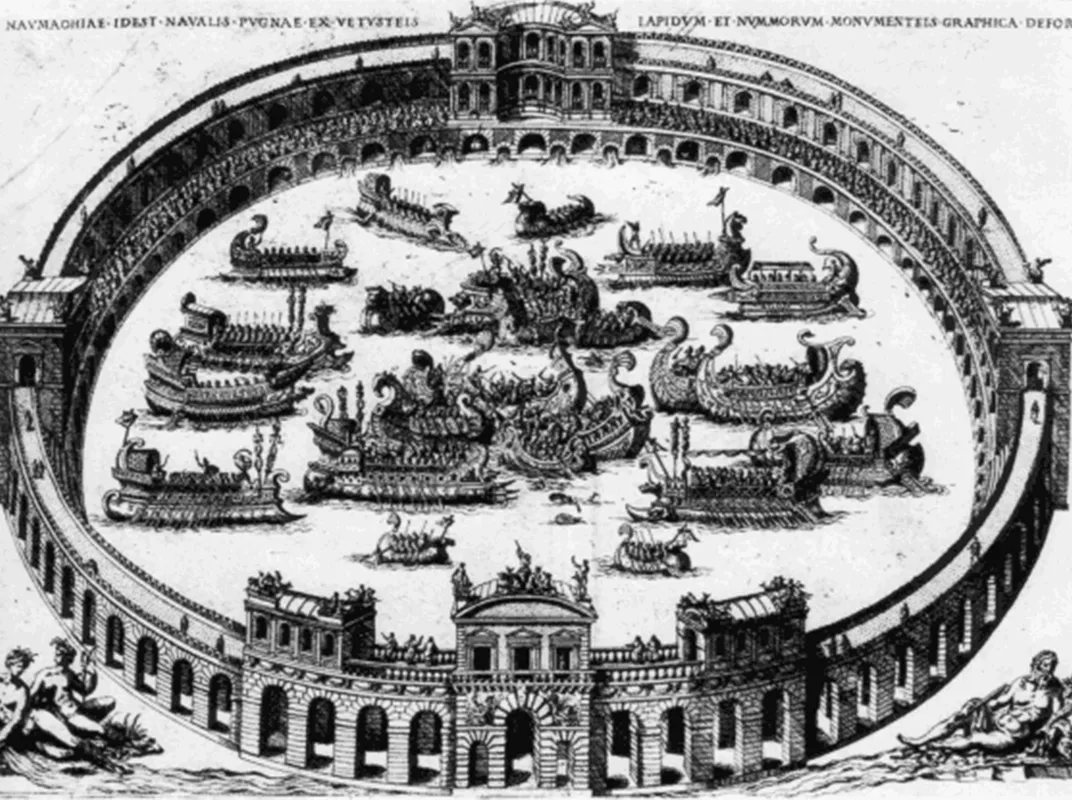

Ancient Rome’s gladiatorial contests are well known for their excessive and gruesome displays, but their aquatic spectacles may have been even more over the top. Rulers as early as Julius Caesar commandeered lakes (or dug them) and flooded amphitheaters to stage reenactments of large naval battles— called naumachiae—in which prisoners were forced to fight one another to the death, or drown trying. The naumachiae were such elaborate productions that they were only performed at the command of the emperor, but there is evidence that other—less macabre—types of aquatic performances took place during the Roman era, including an ancient forerunner to modern synchronized swimming.

The first-century A.D. poet Martial wrote a series of epigrams about the early spectacles in the Colosseum, in which he described a group of women who played the role of Nereids, or water nymphs, during an aquatic performance in the flooded amphitheater. They dove, swam and created elaborate formations and nautical shapes in the water, such as the outline or form of a trident, an anchor and a ship with billowing sails. Since the women were portraying water nymphs, they probably performed nude, says Kathleen Coleman, James Loeb Professor of the Classics at Harvard University, who has translated and written commentaries on Martial’s work. Yet, she says, “There was a stigma attached to displaying one’s body in public, so the women performing in these games were likely to have been of lowly status, probably slaves.”

Regardless of their social rank, Martial was clearly impressed with the performance. “Who designed such amazing tricks in the limpid waves?” he asks near the end of the epigram. He concludes that it must have been Thetis herself—the mythological leader of the nymphs—who taught “these feats” to her fellow-Nereids.

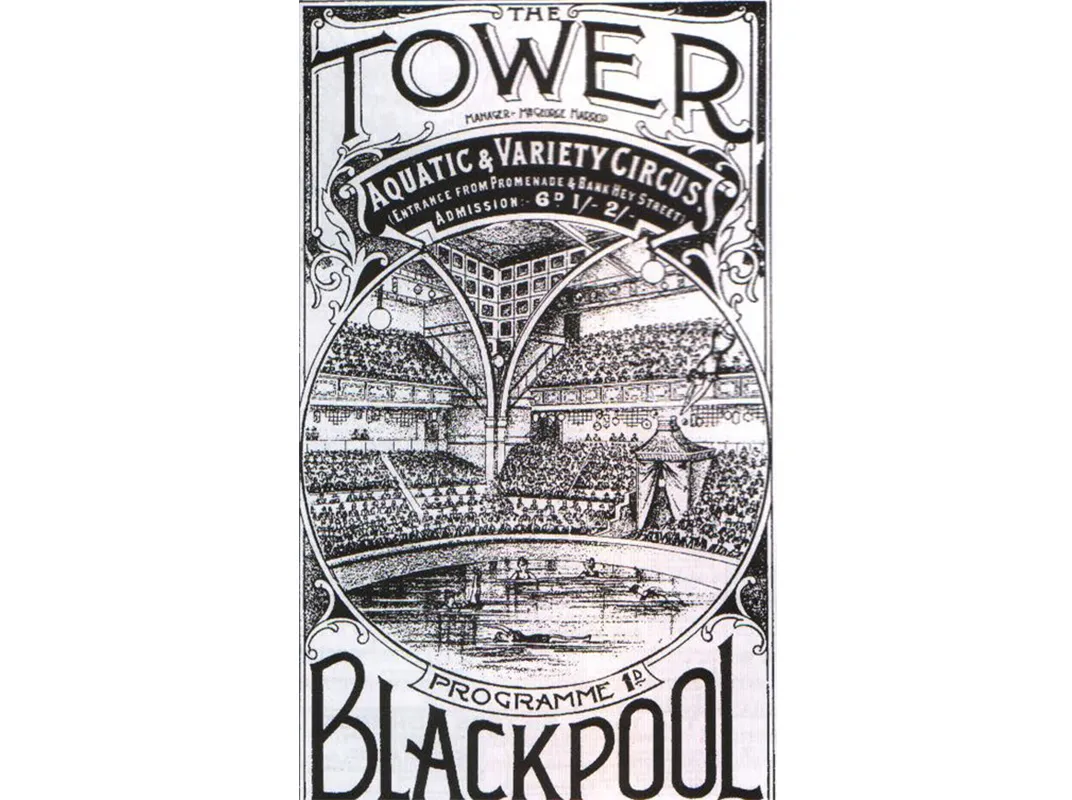

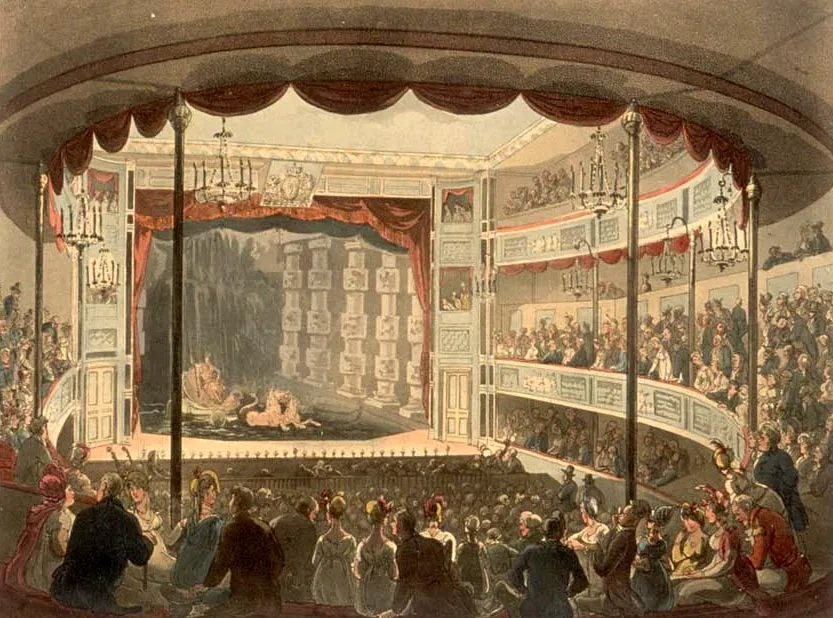

Fast forward to the 19th century and naval battle re-enactments appear again, this time at the Sadler’s Wells Theater in England, which featured a 90-by-45 foot tank of water for staging “aqua dramas.” Productions included a dramatization of the late-18th-century Siege of Gibraltar, complete with gunboats and floating batteries, and a play about the sea-god Neptune, who actually rode his seahorse-drawn chariot through a waterfall cascading over the back of the stage. Over the course of the 1800s, a number of circuses in Europe, such as the Nouveau Cirque in Paris and Blackpool Tower Circus in England, added aquatic acts to their programs. These were not tent shows, but elegant, permanent structures, sometimes called the “people’s palaces,” with sinking stages or center rings that could be lined with rubber and filled with enough water to accommodate small boats or a group of swimmers.

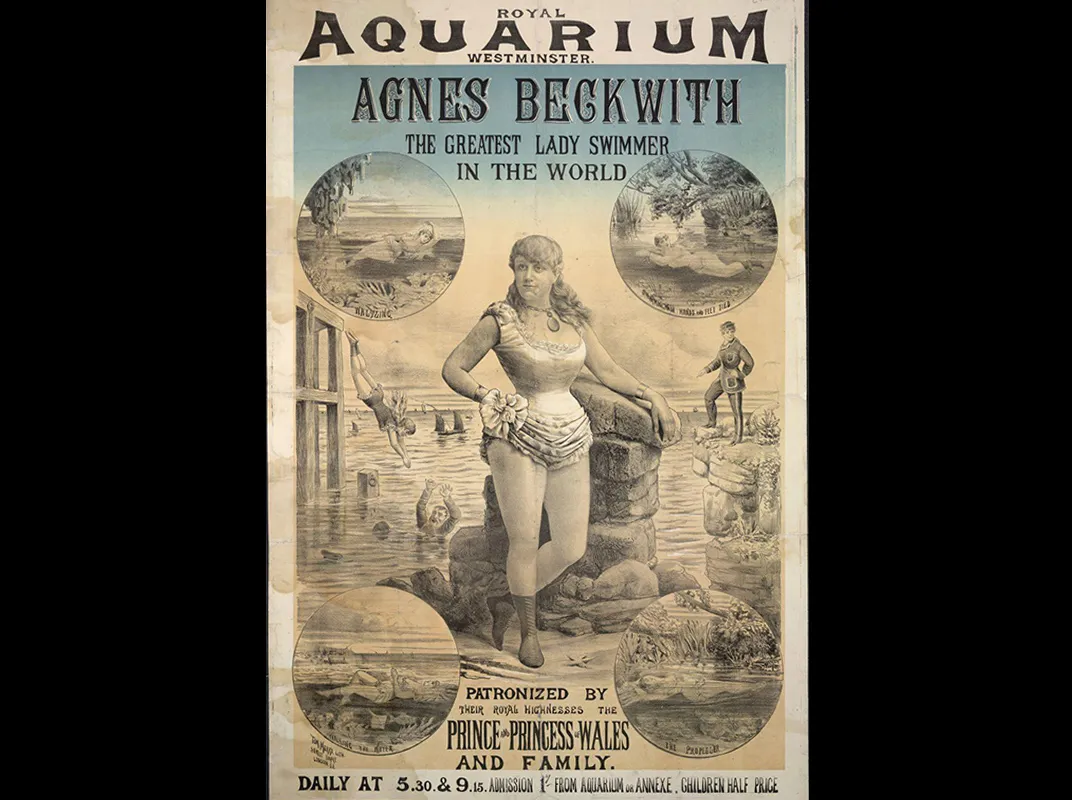

In England, these Victorian swimmers were often part of a performing circuit of professional "natationists" who demonstrated "ornamental" swimming, which involved displays of aquatic stunts, such as somersaults, sculling, treading water and swimming with arms and legs bound. They waltzed and swam in glass tanks at music halls and aquariums, and often opened their acts with underwater parlor tricks like smoking or eating while submerged. Though these acts were first performed by men, female swimmers soon came to be favored by audiences. Manchester (U.K.) Metropolitan University's sports and leisure historian, Dave Day, who has written extensively on the subject, points out that swimming, "packaged as entertainment," gave a small group of young, working-class women the opportunity to make a living, not only as performers, but also as swimming instructors for other women. But as more women in England learned to swim, the novelty of their acts wore off.

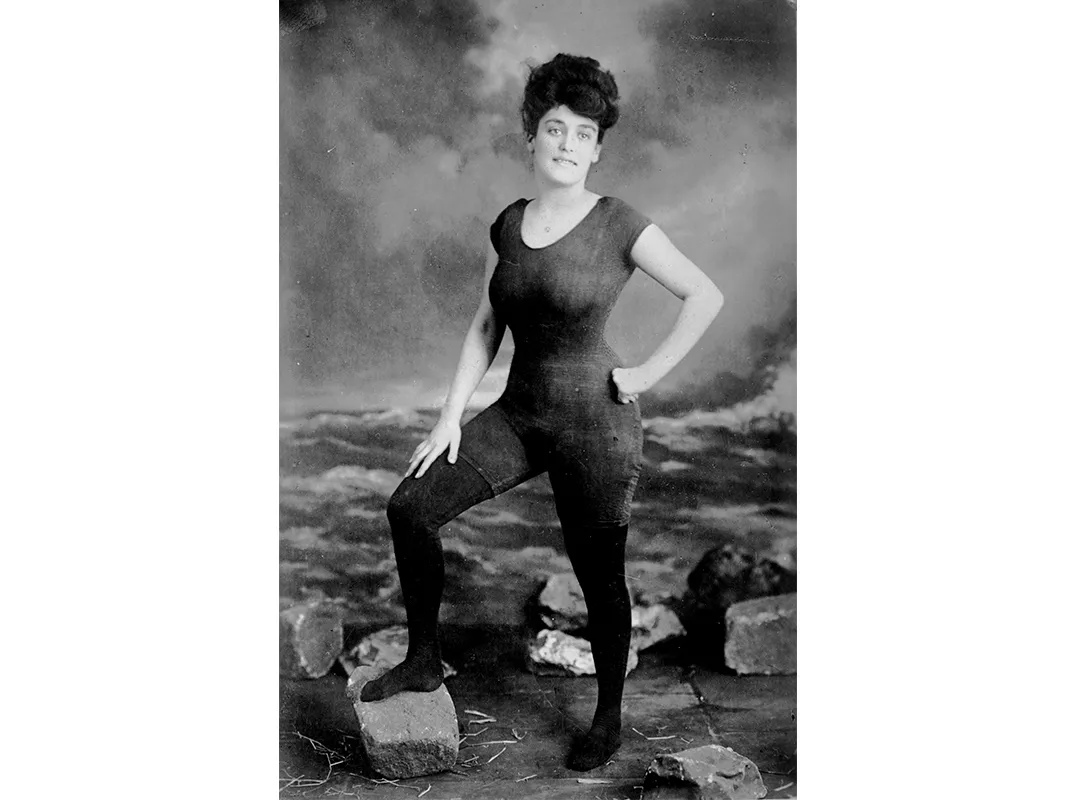

In the United States, however, the idea of a female aquatic performer still seemed quite avant-garde when Australian champion swimmer Annette Kellerman launched her vaudeville career in New York in 1908. Billed as the "Diving Venus" and often considered the mother of synchronized swimming, Kellerman wove together displays of diving, swimming and dancing, which The New York Times called "art in the making." Kellerman's career—which included starring roles in mermaid and aquatic-themed silent films and lecturing to female audiences about the importance of getting fit and wearing sensible clothing—reached its pinnacle when she, and a supporting cast of 200 mermaids, replaced prima-ballerina Pavlova as the headline act at the New York Hippodrome in 1917.

While Kellerman was promoting swimming as a way to maintain health and beauty, the American Red Cross, which had grown concerned about high drowning rates across the country, turned to water pageants as an innovative way to increase public interest in swimming and water safety. These events, which featured swimming, acting, music, life-saving demonstrations or some combination of these, became increasingly popular during the 1920s. Clubs for water pageantry, water ballet and "rhythmic" swimming—along with clubs for competitive diving and swimming—started popping up in every pocket of America.

One such group, the University of Chicago Tarpon Club, under the direction of Katharine Curtis, had begun experimenting with using music not just as background, but as a way to synchronize swimmers with a beat and with one another. In 1934, the club, under the name Modern Mermaids, performed to the accompaniment of a 12-piece band at the Century of Progress World's Fair in Chicago. It was here that "synchronized swimming" got its name when announcer Norman Ross used the phrase to describe the performance of the 60 swimmers. By the end of the decade, Curtis had overseen the first competition between teams doing this type of swimming and written its first rulebook, effectively turning water ballet into the sport of synchronized swimming.

While Curtis, a physical education instructor, was busy moving aquatic performance in the direction of competitive sport, American impresario Billy Rose saw a golden opportunity to link the already popular Ziegfeld-esque “girl show” with the rising interest in water-based entertainment. In 1937, he produced the Great Lakes Aquacade on the Cleveland waterfront, featuring—according to the souvenir program—"the glamour of diving and swimming mermaids in water ballets of breath-taking beauty and rhythm."

The show was such a success that Rose produced two additional Aquacades in New York and San Francisco, where Esther Williams was his star mermaid. Following the show, Williams became an international swimming sensation through her starring roles in MGM's aquamusicals, featuring water ballets elaborately choreographed by Busby Berkeley.

Though competitive synchronized swimming—which gained momentum during the middle of the century—began to look less and less like Williams' water ballets, her movies did help spread interest in the sport. Since its 1984 Olympic induction, synchronized swimming has moved farther from its entertainment past, becoming ever "faster, higher, and stronger," and has proven itself to be a serious athletic event.

But regardless of its roots, and regardless of how it has evolved, the fact that synchronized swimming remains a spectator favorite—it was one of the first sporting events to sell out in Rio—just goes to show that audiences still haven't lost that ancient appetite for aquatic spectacle.

How to watch synchronized swimming

If synchronized swimming looks easy, the athletes are doing their jobs. Though it is a grueling sport that requires tremendous strength, flexibility, and endurance—all delivered with absolute precision while upside down and in the deep end—synchronized swimmers are expected to maintain "an illusion of ease," according to the rulebook issued by FINA, the governing body of swimming, diving, water polo, synchronized swimming and open water swimming.

Olympic synchronized swimming includes both duet and team events, with scores from technical and free routines combined to calculate a final rank. Routines are scored for execution, difficulty and artistic impression, with judges watching not only for perfect synchronization and execution, both above and below the surface, but also for swimmers' bodies to be high above the water, for constant movement across the pool, for teams to swim in sharp but quickly changing formations, and for the choreography to express the mood of the music.

The United States and Canada were the sport's early leaders, but Russia—with its rich traditions in dance and acrobatics, combined with its stringent athletic discipline—has risen to dominance in recent years, winning every gold Olympic medal of the 21st century and contributing to the ever-changing look of the sport.