September 1861: Settling in for a Long War

During this month, the civil war expands to Kentucky and West Virginia, and President Lincoln rejects an attempt at emancipation

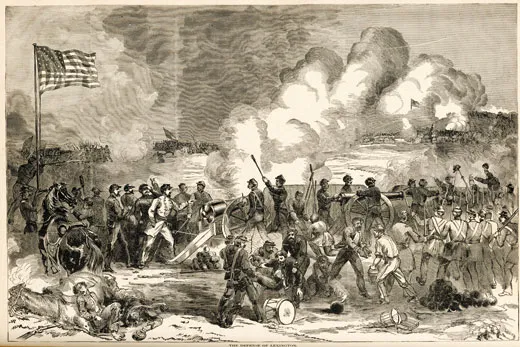

Five months into the Civil War—on September 9—Richmond, Virginia’s Daily Dispatch editorialized that the time for debate had passed. “Words are now of no avail: blood is more potent than rhetoric, more profound than logic.” Six days earlier, Confederate forces had invaded Kentucky, drawing that state into the war on the Union side and firming up the border between North and South.

But who to trust in the border states? “We have had no success lately, and never can have success, while the enemy know all our plans and dispositions,” wrote Confederate war clerk John Beauchamp Jones on September 24 from Richmond. “Their spies and emissaries here are so many torch-bearers for them.” In Washington, President Lincoln confronted disloyalty even to his north; between the 12th and 17th, he ordered troops in Maryland to arrest 30 secessionists, including members of the state legislature.

About the same time, Confederate general Robert E. Lee was waging and losing his first campaign, at Cheat Mountain in Western Virginia. Even soldiers spared direct battle had no easy time. “I must again march without one bite of anything to eat,” the Confederate soldier Cyrus F. Jenkins wrote in his diary from a spot some 80 miles away. “The clouds are flying over us and the rain is falling thick and fast.” Union generals lost a weeklong siege of Lexington, Missouri, but took control of Ship Island, off the Gulf Coast of Mississippi. The island would later serve as a staging ground for the campaign against New Orleans.

Although Lincoln had upheld the Fugitive Slave Act in his inaugural address, the runaway slave question remained fraught. How would Union soldiers treat fugitives they encountered? In a letter to a friend, author and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child quoted a Union soldier commanded to return fleeing slaves: “That is an order I will not obey.”

Lincoln doubted that he had the power to obliterate slavery by decree. In any case, such an act would alienate the crucial border states whose favor he struggled to retain. In late August, Union major general John C. Frémont had issued a sweeping proclamation declaring free the slaves of Confederate sympathizers in Missouri. On September 11, Lincoln ordered Frémont to rescind the order, citing legal questions. (Lincoln’s own more carefully considered proclamation would ripen over the course of the coming year.)

For Mary Todd Lincoln, the president’s wife, the war clouded everything. “The weather is so beautiful, why is it, that we cannot feel well,” she wrote to her cousin on the 29th from the White House. “If the country was only peaceful, all would be well.” Ulysses S. Grant, then a brigadier general in the Union Army, had just confided to his sister Mary: “This war...is formidable and I regret to say cannot end so soon as I anticipated at first.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)