Spared From the Holocaust by His Countrymen, a Jewish Refugee Hopes That Denmark Can Regain Its Humanity

Leo Goldberger will never forget how his fellow Danes kept him safe, but the reaction to today’s refugee crisis gives him pause about his former homeland

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/b1/ebb1c906-3968-450a-bca7-c9900905302b/denmark_family_photo.jpg)

This story was co-produced with Latterly

It was October 1943, and a cold autumn mist was falling on the coast of Denmark. The Goldberger family — mother, father and four children — huddled in a clump of bushes near the beach. They peered into the darkness, hoping to spot a blinking light. Across the water were the shores of Sweden.

Leo Goldberger was 13, the son of a Jewish cantor. He was thinking about the strange series of events that had led to this moment: the Nazi invasion of Denmark, the quiet resistance movement that had helped protect Danish Jews, the rumors of impending mass deportation. “I felt what I can only describe as an absolute rage,” Goldberger remembers. “I kept thinking: What the hell did we do?”

“I had this fantastic desire to hit. Hit back,” he says. But those feelings were interrupted by a light that flashed somewhere in the distance. It was time to go.

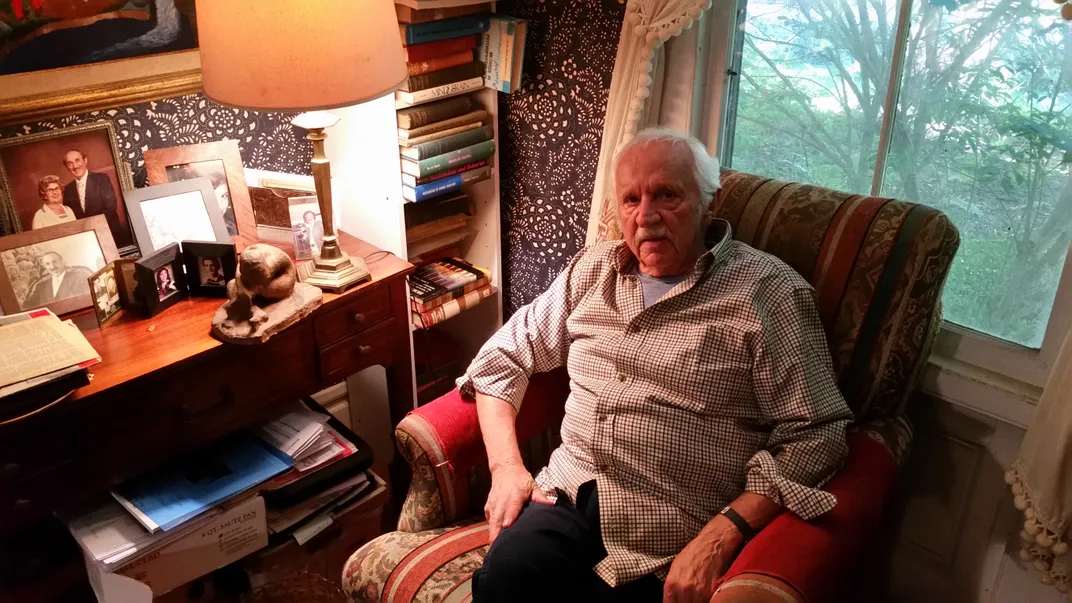

Goldberger’s father took two of his children in his arms. Goldberger carried a bag, his favorite flashlight and a clay sculpture he still keeps in his study. “We walked right into the water,” he says. “Shoes and everything wet.” The water reached Goldberger’s knees, then his waist and then his chest. His soaked clothes clung to his skin.

They reached a small Danish fishing boat, and one by one, they climbed aboard. The boat contained around a dozen other Jewish refugees. “We had to be down there in the hold, covered with canvas,” Goldberger says. He felt seasick. The ship rose and fell with the waves, and the smell of fish sank into everything. “It was absolutely noxious.”

Late in the night, Germans boarded the ship for an inspection. In the hold, under the filthy canvas, the refugees experienced a moment of quiet terror. They heard voices and footsteps. The Germans decided it was simply a fishing vessel, and they sailed on.

* * *

Today, Leo Goldberger is 85 and lives along a one-lane highway in the woods of western Massachusetts. Tall trees stand watch over his house. Since he retired from his job as a New York University psychology professor, he has led a quiet life here.

In the evenings, Goldberger watches the news on television, and last year he began to see a familiar story. Thousands of refugees from Syria, then tens of thousands, were making the long journey to Europe. Night after night, news reports showed families trying to find their footing in places where Goldberger himself had once lived — Sweden, Denmark, the modern-day Czech Republic.

As a former refugee who narrowly escaped the Holocaust, Goldberger identified with the Syrians he saw on TV. “When I see a family just trying to get on a piece of junk boat,” says Goldberger, “my heart goes out. I have a tendency to cry. Because I identify.”

“It’s a terrible, terrible feeling — being on the run,” he continues. “It just brings back memories.”

What seemed less familiar were the stories that followed — stories about European hostility to refugees in the form of right-wing protests and restrictive immigration laws.

Goldberger's time in Nazi-occupied Denmark actually reinforced his faith in humanity. He looks back fondly at his life in Denmark, because ordinary Danes saved his life.

But when Goldberger looks at today's Europe — which faces the largest refugee crisis since the one he himself lived through — he wonders if new arrivals will experience the same compassion he did.

* * *

The Goldbergers’ 1943 trip to Sweden was the family’s last close call in a string of harrowing experiences. Germany had invaded Denmark in 1940, and although Jews weren’t immediately targeted, the German occupiers collected lists of Danish Jews. They also arrested and deported about a dozen Jewish leaders.

“The Germans came and tried to take my dad,” Goldberger remembers. One night in Denmark, he awoke to a sudden banging. It was the sound of German rifle butts against the door.

The Goldbergers stayed where they were. There was a moment of silence so tense that Leo could hardly stand it. “I was afraid they would become angry enough to break down the door and shoot,” he says. After a moment, the upstairs neighbors told the Germans that the Goldbergers were on vacation.

These were the kinds of experiences that made escape seem urgent. Life seemed to get riskier by the day — though Jews weren’t without allies. In order to help Jews cover the costs of escape, “the Danes began to collect money,” Goldberger says. “They would even look in the phone book to see Jewish names. And they would come to your house and say, ‘Do you know what’s happening? You’ve got to get out. We’ll help you.’”

When the Goldbergers finally clambered into that Danish fishing boat, they were just one of thousands of families who were secretly assisted by ordinary Danes. Over the course of two weeks, a haphazard flotilla of fishing boats brought over 7,000 people to the safety of neutral Sweden. The Goldbergers spent the rest of the war there.

Historians describe those weeks as the “Rescue of the Danish Jews.” Denmark became an exception in World War II: It was the only Nazi-occupied country to rescue almost all of its Jewish population.

There are a few reasons for this. The first, says Goldberger, is that Danish Jews were well-integrated for generations. “We were Danes,” says Goldberger. “We spoke the language, we sang their songs, we ate their food.” It’s no accident that one of the best-known accounts of the experience of Danish Jews, written by Bo Lidegaard, is called Countrymen.

Of course, there are other accounts that paint Denmark’s actions in a less-flattering light. The country capitulated quickly when Germany first invaded. The Danish government retained a level of autonomy, but only because many Danes were willing to collaborate with Germans. The Danish Nazi Party had nearly 30,000 members, and German leaders praised Denmark as a model occupied nation.

It was in that context that ordinary Danes tried to undermine their German occupiers. They focused less on violent sabotage and more on quieter forms of resistance — like helping Jews. “The Danes were so angry at the Germans,” Goldberger says. “That was an easy way for them to rebel.”

* * *

When Goldberger tells his own story, he frames it in the language of psychology. “I had been conditioned to be in a war zone,” he says, referring to the air raid shelters in which his family took refuge. He even offers a psychological explanation for his intense memories of the boat trip to Sweden.

“If you think in terms of what happens to human beings as they are reduced to the lowest level, you get to a point where things like smell and taste become magnified,” he says. “That’s animalistic.” Goldberger says that many Danish Jews who escaped to Sweden remember that same overwhelming smell of fish.

Goldberger’s psychological framework comes from the life he led after the war. After Germany surrendered, the family returned to their apartment in Copenhagen.

Their Danish homecoming was vivid but short-lived. “It was just jubilation, month after month,” Goldberger remembers. One night, he simply didn’t go home, and when he returned the next morning, his father was surprised to hear him up so early. “Getting up so early for the morning service?” he asked. Goldberger was doing nothing of the sort, of course — but that was a good cover story. “So I had to schlep to the synagogue! I never told him I had not been at home all night.”

Outside of Denmark, however, devastation cast a shadow over end-of-war celebrations. Goldberger’s father came from central Europe; not one of his brothers and sisters had survived. In 1945, the Nuremberg Trials documented the unimaginable scale of Nazi death camps. Danes learned along with the rest of the world that German doctors had not only murdered but also experimented on Jews.

“My dad seemed to get more and more depressed,” Goldberger says. “That’s when he started to look around for another place to live.”

In 1947, the Goldbergers left Denmark again, this time for good. They settled in Canada, where Goldberger enrolled at McGill University. That’s where he started to think deeply about the workings of the human mind.

“I was absolutely curious to find out what other people were thinking who didn’t speak my language, who looked different than me,” he says. This wasn’t just an academic interest — it was also self-interest. As a young man, he’d constantly encountered strange cultures and languages. English was his fifth language, behind Czech, German, Danish and Swedish.

“You have to adapt,” he says. He remembers going on a first date with a beautiful woman in Canada. “She kept saying to me, ‘You’re pulling my leg.’ And I kept saying, ‘I'm nowhere near your legs!’” says Goldberger, laughing. “Idioms. Impossible.”

At the time, many psychologists were following in the footsteps of Freud, focusing on dreams and the unconscious. Goldberger chose a specialty closer to home: the psychology of adaptation.

* * *

Goldberger’s research took him to Cornell Medical Center in New York City, where he joined a team of social scientists. “We were a group of interdisciplinary researchers studying adaptation to life in America — just like you might be interested in me, and how I adapted to this new culture,” he says.

Goldberger knew from experience that survival isn’t just a matter of physical safety. It’s also a matter of achieving a sense of security in one’s own mind.

One of his studies focused on a group of Chinese political exiles living in New York. In Goldberger’s mind, the study seemed like a good way to investigate the impacts of displacement. He and several colleagues wanted to understand “the stress of being dislocated from one culture, China, to another.” They saw that as their mandate.

It was only years later, long after the reports were filed, that Goldberger learned he had been betrayed. His superiors, he discovered, weren’t interested in adaptation. “Nobody gave a damn about that! They were only interested in finding out whether we could identify potential spies.” The team’s reports had been used — many would say misused — to identify men with the resilience needed for espionage work.

What Goldberger found out is that his research, and that of several colleagues, had been secretly funded by the CIA. Cornell Medical Center had taken money to launch covert Cold War research — not only to recruit Chinese spies, but also to understand the impact of harsh interrogation techniques. They had never informed many of the scientists who conducted the research.

“I was always locked out of the most secret stuff,” says Goldberger. “Because I wasn’t a citizen, I couldn’t get clearance.” The United States had helped him find his feet as an immigrant, but now at Cornell it had shattered his trust. “I was lied to,” he says.

The cruel irony is that, after the Holocaust, international regulations were supposed to make situations like these impossible. “After the Nuremberg trial, there was a law passed that required informed consent,” Goldberger points out. All subjects were supposed to know why and how they would be studied.

The aim, of course, was to outlaw unethical experiments like the ones Nazis had conducted on Jews in concentration camps. Goldberger had lost many of his own family members in those camps.

The research conducted by Goldberger’s team didn’t have the violence and racism of Nazi experiments on Jewish prisoners. But decades later, Goldberger still feels that he was wronged. “Why should an investigator not be held to the same standard, and get informed?” he asks. “So he knows what he’s doing?”

* * *

Goldberger’s house in western Massachusetts is full of echoes of the past. The sculpture he made as a kid, which he carried on the fishing boat from Denmark to Sweden, sits on a shelf. There’s a picture of his father’s religious students in Czechoslovakia, almost all of whom died in the Holocaust. There are newspaper clippings that highlight Goldberger’s early research, some of which now leaves a bad taste in his mouth.

It’s easy to look at these symbols and feel dejected. But even when he talks about ugly chapters in the past, Goldberger sounds like a willful optimist. “Once I came to this side of the ocean, I tried to put it behind me,” he says. That doesn’t mean he tried to forget — just that he focused on the heroes rather than the villains. He even edited a book called Rescue of the Danish Jews: Moral Courage Under Stress.

The relationship between man and country is complex; that’s something Goldberger knows from experience. In the Denmark of his youth, Jews were Danes, and ordinary Danes helped Jews — even at a time when Danish Nazis ran the government. In the United States, Goldberger felt welcomed as a Jewish immigrant, but betrayed as a young scientist.

He still feels connected to the country where he grew up. A few months ago, Denmark started making headlines for its response to the refugee crisis. The country has been accused of trying to drive asylum seekers elsewhere in Europe. “I write to my Danish friends that they should be ashamed of themselves,” Goldberger says. “They should be ashamed of the small contribution they’re making. They are doing the absolute minimum.”

In January, a new law made it harder for asylum seekers to bring their families to Denmark. It also legalized the seizure of refugee property — a move that some compared to the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany.

Goldberger says he can understand the property regulations, which he sees as a way to cover the costs of government services. But he’s disappointed that under the new rules, family members will be kept apart. During World War II, family was his one constant source of stability and security.

Denmark, like the United States, has a track record of helping refugees. But Goldberger doesn’t think that’s any reason to rest on the laurels of history. In the challenges of the present, he hopes Denmark can live up to its past.

Editor's Note, March 25, 2016: An earlier version of this story stated that the Chinese emigrants studied by Goldberger were in Taiwan. They were in New York. It also said that he wrote the book about Danish survivors; he edited that book.