A Portrait of an American Hero and a Generation That Is Slowly Fading Away

Photographer Dan Winters shows us the modern-day life of an unheralded World War II veteran

Editor's Note, June 27, 2016: Smithsonian has learned that Ray Halliburton died at age 91 on June 11, 2016, surrounded by his friends and family members.

The memories are slipping away. The lived experience has faded as life went on and the years accumulated, clouding that time when the future was at risk because the world was totally at war. It exists primarily as history now, to all but a few. And even those few are hard-pressed to remember.

“Eisenhower,” says Ray Halliburton, “Patton...” He frowns, trying to recall the chain of command he once knew implicitly, from the Supreme Allied Commander to his own platoon leader. Not only do the names escape him, so do the units he was part of: the division whose patch he wore, the regiment he served in, the line company he fought with.

“Eisenhower,” he says, trying again, “Patton...”

Ray Halliburton is 91 years old and his body, like his memory, has withdrawn to a skeletal core. He is back-bent and frozen-hipped, unable to walk without wobbling. He still has the strong hands of a man who picked and toted watermelons for 50 years, but they are attached to frail arms dangling from slumped shoulders. The smooth face of the young soldier has been weathered by Texas summers into sinewy furrows. The pale blue eyes are lively, though, and glare sometimes when he wants to be understood, straining to pierce the fog of lost time.

Military records indicate that Ray Halliburton was a member of K Company, Third Battalion, Tenth Infantry Regiment, Fifth Infantry “Red Diamond” Division, in Patton’s Third Army. He was a corporal when they went ashore in France in July 1944, one month after D-Day. After three months of fierce combat across 500 miles he had risen to staff sergeant and squad leader, not yet 20 years old.

He can remember being afraid. “I didn’t like to be where there was shooting unless I was careful,” he says. “If you’re going into war I’m telling you to be very careful. I seen some terrible shooting. You talk about being scared.”

Lying in bed, he talks about some of his men. “Was near the Moselle River, a German 88 exploded right on top of us, air burst in the trees. Like getting hit by lightning. Killed two of my boys, fine boys, I loved the both of them. One died in my arms. He was a good man, had nerve and had guts, smart, too.”

He can’t quite recall that man’s name, however. “Was Lidell, Lyon, something like that,” he says, glaring. “He died in three minutes. I held onto him the whole time. He told me to tell his mother.”

Casualty lists indicate that the man was Pvt. George DeLisle of Michigan, who was killed in action on September 9, 1944, age 19. The other man was Pvt. Arnold Davis of West Virginia, who died of his wounds a month later.

He better remembers his closest friend: “Tech. Sergeant Hughes, he was just like my brother. He was platoon sergeant over me, I was one of the squad leaders. Then a strange thing happened one night. We was in Germany then. We stayed together in a trench, it was freezing.”

In the first week of December 1944, the 3rd Battalion was among the first Allied forces to cross the Saar River into Germany itself. Company K was guarding the unit’s right flank near the town of Ludweiler.

“Sergeant Hughes says to me, ‘Sergeant Halliburton, me and you been a long ways, all across France, we in Germany now. But something’s fixing to happen, we’re gonna be split up.’ I said, ‘Oh, no, Sergeant Hughes, we’re going to Berlin together.’ He said, ‘I wish we could, but, no, something’s fixing to happen.’”

Ray abruptly sits up in bed, propped on an elbow, frowning, straining to get a bead on the ghostly past. “Next morning he woke me up, told me to get the men up, we’re under attack. Germans opened up with machine guns, ta-ta-ta-tat, cuttin’ the grass all round us. Good thing we was laying down. Sergeant Hughes said, ‘Sergeant Halliburton, you stay here. I’m going see what’s going on.’

“He got up and run about from here to there,” says Ray, pointing out the window to the neighbor’s house. “They just cut him all to pieces.”

Tech. Sgt. Victor L. Hughes of Kentucky was killed in action December 5, 1944. The German attack that morning was a probe for the massive counteroffensive that came 11 days later and began what history calls the Battle of the Bulge.

“When I looked up the other way three Germans was standing there, pointing them burp guns at me. What could I do? Anybody tells you they won’t surrender when they got three guns pointed at ’em, they ain’t been there. Forty good men surrendered that day.”

Ray spent the last six months of the war as a half-starved POW in Stalag IIIB, north of Berlin.

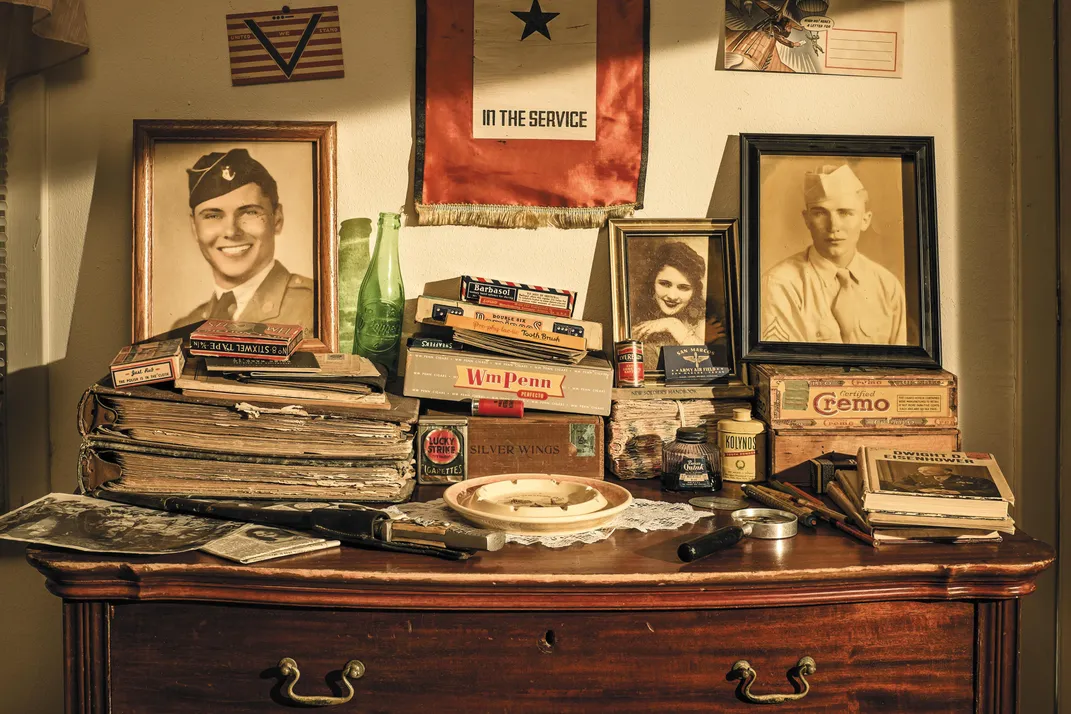

Ray eases back on his pillow. He spends much of his days in bed now, watching soap operas and televangelists, drifting. His most poignant war memories are of his older brother Johnnie, who went off to war three years before Ray. “I loved Johnnie, he was my hero. Six-foot tall, powerfully built man. Taught me to hunt, taught me to fish. Do anything for you, smile when he did it.” The photograph of Johnnie that sits atop a bureau in Ray’s home shows a strikingly handsome soldier with a movie star smile. Ray and their mother saw him off at the train station in San Antonio. “I saved up to buy him a good watch before he left,” he says. “Real nice Elgin watch.”

Johnnie Halliburton shipped out with the 36th Infantry “Texas” Division, one of the first U.S. units to go overseas. They landed first in North Africa, then led the invasion of southern Italy in early September 1943.

They were Texas farm boys, the Halliburton brothers, two of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II, nearly all of them anonymously in the broad view of history. Neither Johnnie nor Ray became famous or even noteworthy. No school or road was named for them, no book mentions them. They played their parts in a terrible but necessary international struggle and would be satisfied by victory, and that would be sufficient.

Like most of those unsung soldiers, Ray Halliburton came home from war to begin a new life as an ordinary citizen. For him that meant the small towns and sandy soil of central Texas, where farm life was normal and constant and not so threatening. He settled near Luling, a crossroads village renowned as the “Watermelon Capital of America.” Grocers’ trucks would arrive from as far away as Chicago and Baltimore to load up at the Saturday market with sweet local melons, and Ray would be there to supply them. After a couple of decades he added tomatoes to his inventory, but that was as complicated as he let farming get for him.

He wasn’t home long before he waved at a pretty girl he saw on the street one day in the nearby town of Gonzales, and she smiled back at him. Ray married Ethel Johnson in 1949, they stayed married for 34 years and they raised two sons together, Bobby, the youngest, and Johnie, named for the brother who never came home.

“There’s no telling what Johnnie coulda been,” Ray says of his older brother, shaking his head. “Everyone that ever met him wanted to be his friend. He was something else, I’m telling you.”

Twice-wounded, decorated for bravery, and promoted to platoon sergeant during the bloody Italian campaign, Johnnie Halliburton and the Texas Division next invaded southern France along the Côte d’Azur on August 15, 1944. Eight days later a German artillery shell made a direct hit on Johnnie’s tent in the night.

“Only way they could identify him was they found an arm still had that Elgin watch on it. The watch I gave him. I think about that all the time. I miss him. But I do believe I’ll see him again.”

**********

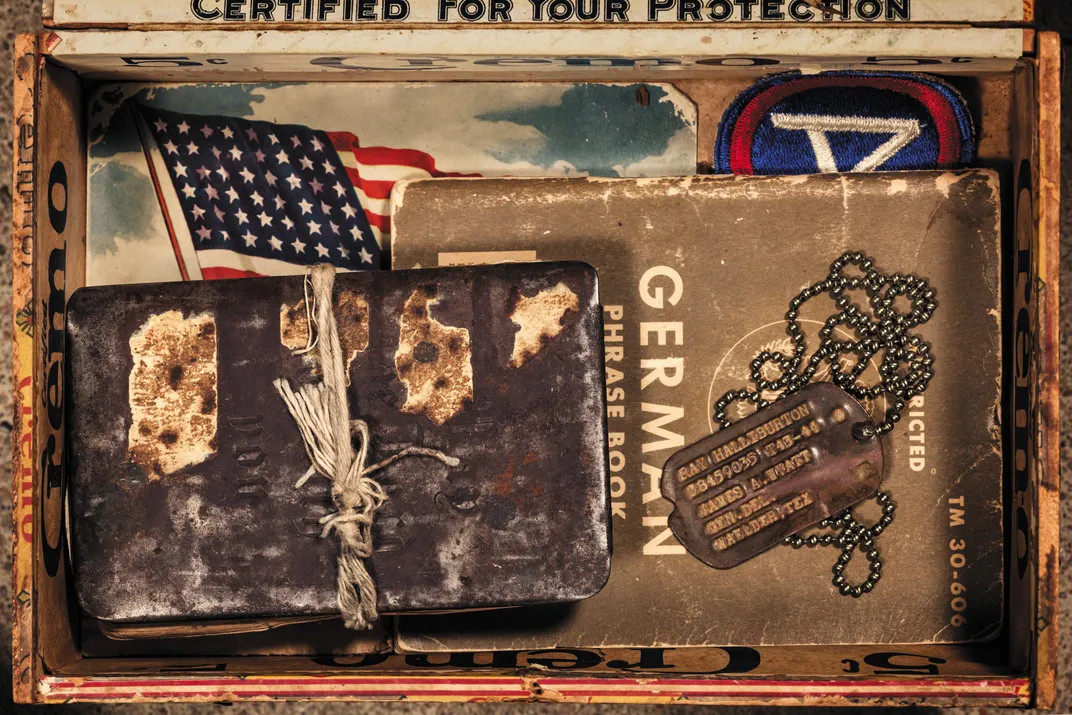

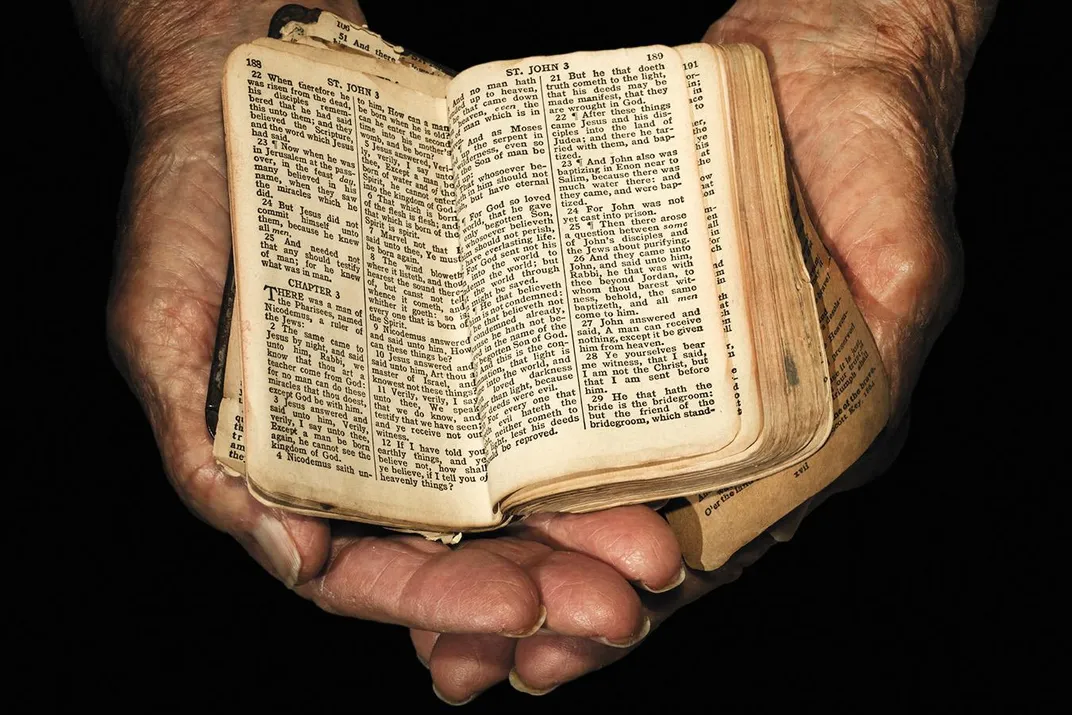

Ray Halliburton keeps a few mementos in an old cigar box. There’s a Third Army patch he wore on his shoulder in the furious charge across France under Patton; his dog tag, a warped piece of stamped tin that still identifies a vital part of him; an olive drab German phrase book, which came in handy during his time as a POW. The most worn item in the box is the pocket-size New Testament that the Army issued him, sometimes called a “Roosevelt Bible” for the frontispiece from FDR. Ray’s copy is held together with string around crumbling covers and the dog-eared pages show 70 years of serious attention: a talisman that connects him still to those desperate months and provides him with a reason for his survival.

“God almighty knows where I was, he helped me many times. I was in many dark places but he saved my life. The Bible says if you love me, keep my commandments, and I’ve tried to do that. I owe him that.”

Only 5 percent of the 16 million veterans of World War II are still with us. Another 500 pass away every day, taking their memories with them. It won’t be long before all that we have left are museums and memorials, statues of generals, history books. That lived experience is vanishing before our eyes; we are losing a physical relation to the generation that saved the nation and propelled it to greatness. Their time is almost past now, and as inspiration turns to mourning we are all diminished.

Related Reads

Road to Seeing