November 1861: Flare Ups in the Chain of Command

As Union generals came and left, personalities clashed and Southern farmers set fire to their fields

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-McClellan-Lincoln-631.jpg)

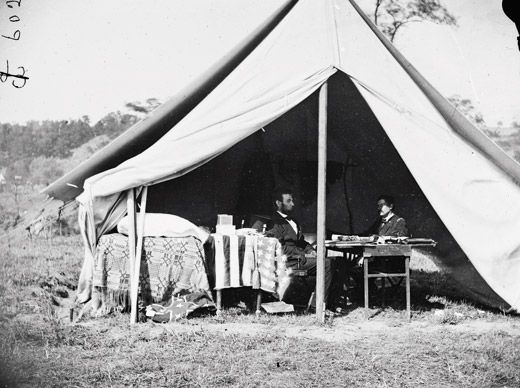

On November 1, George B. McClellan assumed the role of general in chief of the Union armies, a post voluntarily vacated by the ailing 75-year-old Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, who had been a target of McClellan’s barbs in the press. The promotion inflated McClellan’s already significant ego, and he would spar with Lincoln throughout the war. When the president visited McClellan at his home later in the month, McClellan simply went to bed, as Lincoln cooled his heels.

By early November, the president relieved another general, John C. Frémont, of command in the West. Frémont was replaced mid-month by Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, of whom Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles would later snipe: “Halleck...plans nothing, suggests nothing, is good for nothing.”

In the field, soldiers were concerned with a more immediate matter: food. Pvt. Lucius Barber of the 15th Illinois Volunteer Infantry in Missouri later recalled that a “neutral reb” came by the camp selling apples. “He inadvertently betrayed his sentiments and...the boys relieved him of his apples in less time than it takes to write it.” In New York, Pvt. David Day of the 25th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry complained in his diary of a mutton soup that “if [it] didn’t smell to heaven, it must have attained a high altitude above the city.” He had better luck the next day in Philadelphia, where he feasted on “boiled corned beef, tongue, ham, brown and white bread, butter, pies, cake, fruit, tea, coffee, milk, etc.”

On the 6th, Jefferson Davis was elected to a six-year term as president of the Confederacy. In the days following, Union forces encountered little resistance in gaining an important foothold in South Carolina’s Sea Islands; Savannah and Charleston now lay within reach; Robert E. Lee wrote to the Confederate secretary of war, Judah P. Benjamin, “We have no guns that can resist their batteries.” Later in the month, planters near the coast set fire to their cotton fields. “Let the torch be applied whenever the invader pollutes our soil,” declared the Charleston Mercury.

Tensions flared between the Union and England. On the 8th, the British ship Trent was stopped by members of the U.S. Navy, who removed two Confederate envoys from the ship. Parliament erupted in anger, sending some 10,000 troops to Canada. Lincoln, declaring it best to fight “one war at a time,” released the Confederates to avoid a major confrontation. On November 14, novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a British friend that “the whole world, on this side of the Atlantic, appears to have grown more natural and sensible, and walks more erect and cares less about childish things. If the war only lasts long enough (and not too long) it will have done us infinite good.”

On the 30th, Pvt. Day wrote that “last Thursday was observed...as a day of thanksgiving to God, for his manifold mercies and bounties to the erring children of men.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)