How the Mustang, the Symbol of the Frontier, Became a Nuisance

A mainstay of Western culture, the free-roaming stallions are now a force to be reckoned with

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/80/be80d2f7-3763-48f7-b025-c762a4c5b7e8/may2017_h05_phenom.jpg)

There’s a reason that the logo for Ford’s top-selling sports car depicts the galloping horse in profile. It’s the same reason North American Aviation bestowed the name Mustang on its P-51 fighter plane, and that the wild horse was a favorite subject of Old West painter Frederic Remington: Few symbols are more evocative of power and breakneck freedom, or of the untamable frontier spirit. Just the word “mustang,” an ad executive involved with the Ford brand once said, “had the excitement of wide open spaces. Plus, it was American as all hell.”

Which makes it all the more astonishing that the horse has a new reputation: that of a pest. The American West is overrun with wild horses and burros, with nearly 70,000 running free on federal lands, or nearly three times the number considered environmentally sustainable. They are “eating us out of house and home,” says Laura Snell, an agronomist at the University of California. Mustangs pick ranges clean of essential plants and trample streamsides and pond banks, fouling the water that fish and other animals depend on. In northeastern California, a preserve on the Devil’s Garden Plateau produces about 30 million pounds of usable forage per year. But the horses there require nearly six million pounds more than that, according to Snell’s research, leaving little for other animals and depleting the land before it has a chance to replenish itself. “If we don’t act now,” equine biologist Sue McDonnell has said, “there will be parts [of the American West] that will be lost effectively forever.”

To understand how we got to this point, you have to rewind the clock more than 500 years. Along with dangerous diseases and firearms, the Spanish conquistadors brought horses to the New World beginning in the early 16th century. Horses that escaped or were allowed to roam free eventually formed large herds that ranged across grasslands from modern-day Colorado to the Pacific. Thus the name, from mestengo—the Spanish for “stray.” Later, many horses were tamed by Native American warriors as battle steeds.

By the early 20th century, as many as two million mustangs roamed through the West, but commercial slaughter reduced the population: Horse meat was long a popular ingredient in dog and cat food. In 1971, Congress, calling wild horses and burros “living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West,” passed a law that led to new reserves and shielded the animals from culling.

The Bureau of Land Management has carried out this mission for nearly 50 years. But in part because natural predators such as wolves and mountain lions have been so reduced by government hunting policies designed to protect cattle and other livestock, horse populations have soared. To deal with this, federal officials have regularly rounded up horses and steered them onto private land leased from ranchers or into federal corrals, but at unsustainable costs. Every so often, when the BLM considers a mass-euthanasia program to cull the herds, popular outrage wins out. Last September, a proposal to euthanize 45,000 horses that the Humane Society called “a sort of ‘Final Solution’” was halted after a public outcry.

Animal rights activists call for setting aside more land for preserves, and some hope that improved birth control drugs, which can be administered by dart, can curtail the horse population boom. But implementing a plan like that would be costly and onerous—you have to get to the horse to dart it, and for now the drugs are effective for just 22 months, so they’d have to be treated repeatedly.

The mustang, its mane flying and hooves thundering, will always have a hold on the American imagination. But with the shrinking of the frontier, the emerging view is that even wild horses live at odds with their environment. The “green / of the field is paling away,” as James Dickey put it in his poem “The Dusk of Horses,” and “They see this, and put down / their long heads deeper in grass.”

Related Reads

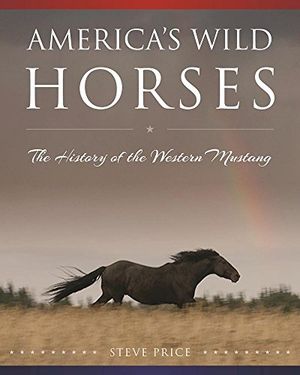

America's Wild Horses: The History of the Western Mustang