The Mining Millionaire Americans Couldn’t Help But Love

Unlike the other one-percenters of his age, John Mackay gained his countrymen’s admiration. But in an ironic twist, it means he’s little known today

:focal(377x204:378x205)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/17/35/17352749-70a5-4d45-badb-0ea073e884f7/unrs-con-virginia-mine-wr3.jpg)

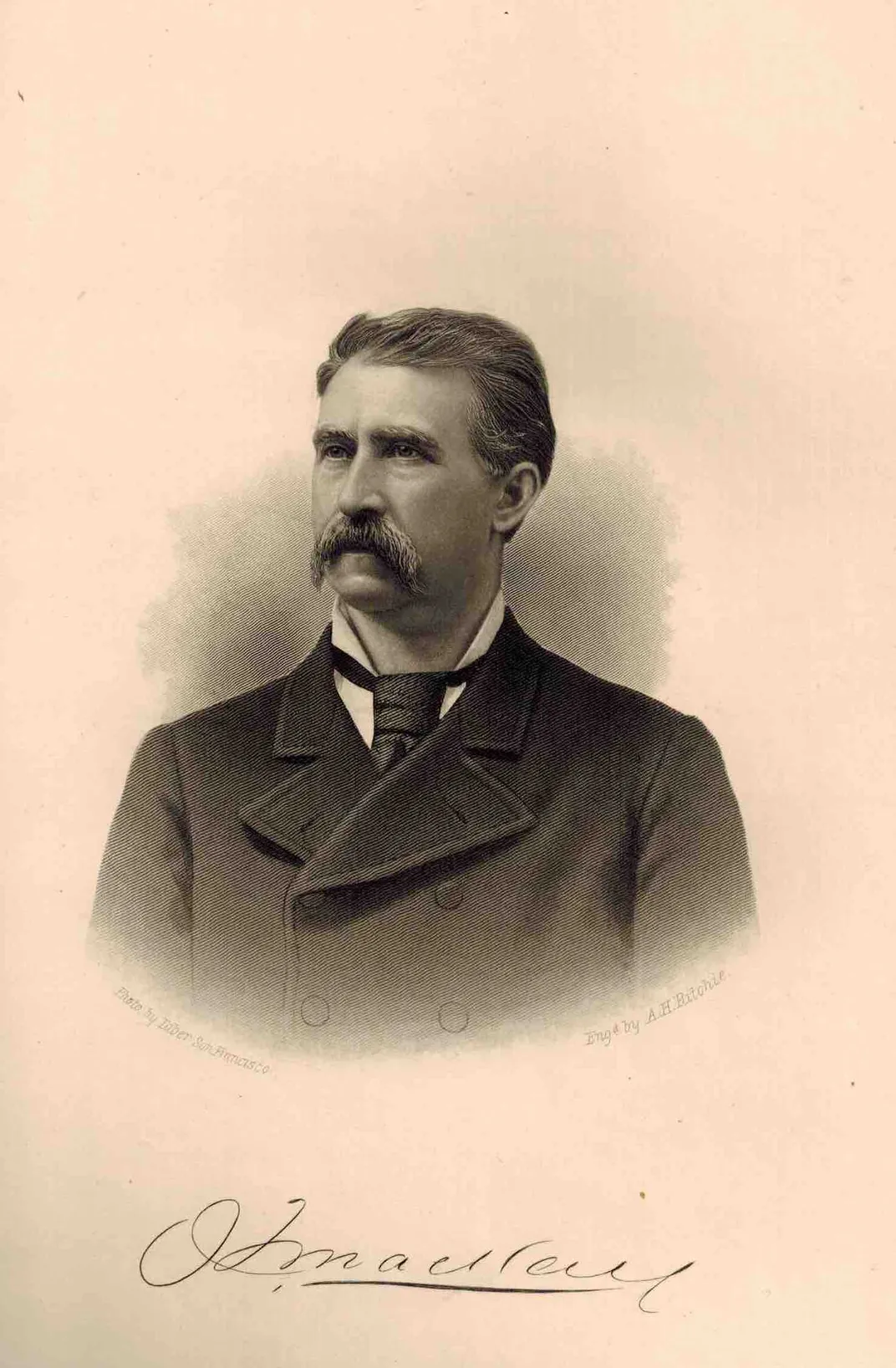

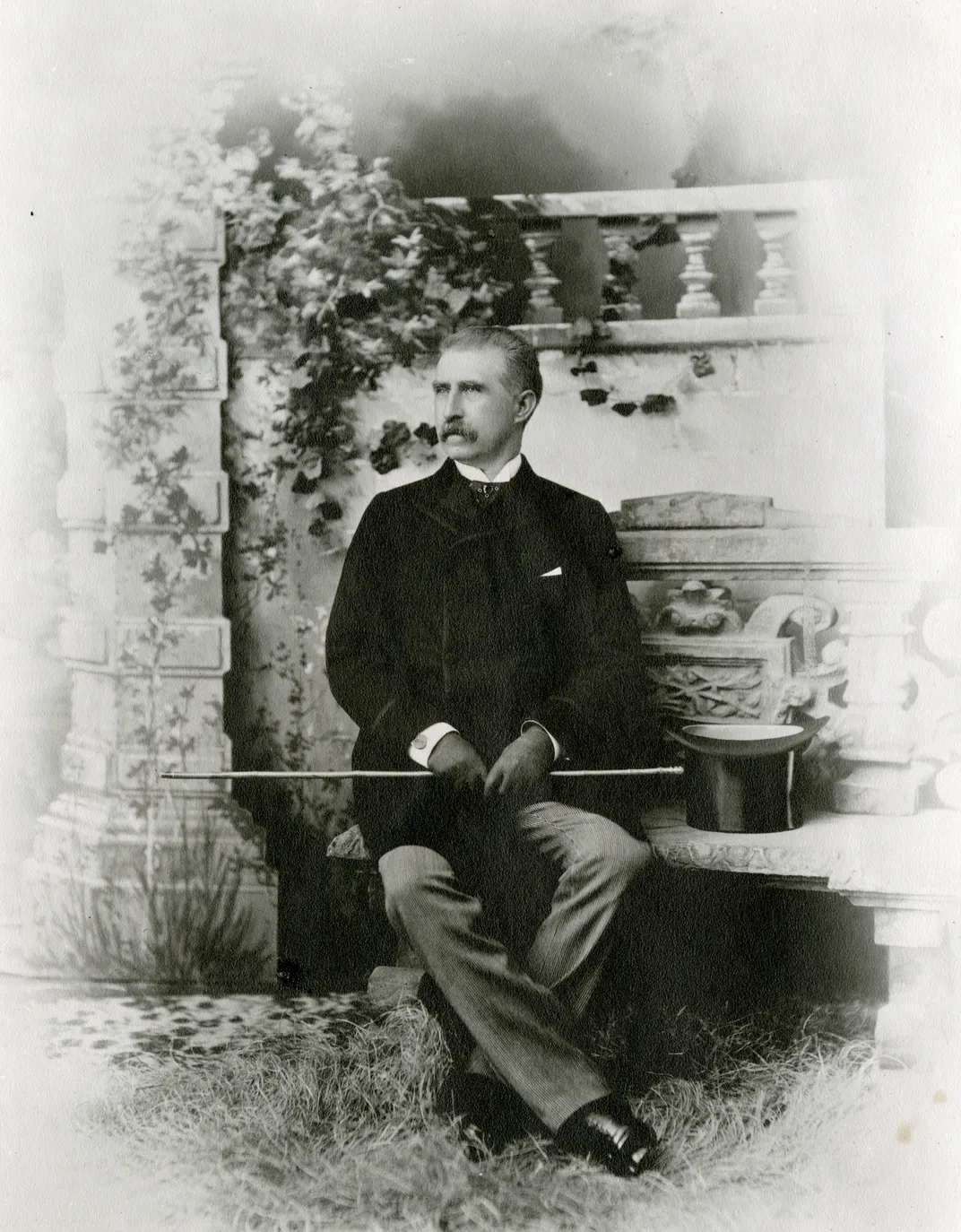

John Mackay’s was once the most beloved rags-to-riches story in America. A penniless Irish immigrant brought to New York City as a child, he’d risen from the infamous Five Points, the nation’s most notorious slum. When Mackay sailed from New York en route to California in 1851, he had no name, no money, and not a single influential friend on earth. He’d possessed nothing but strong arms, a clear head, and a legendary capacity for hard work. In the eyes of the times, his road to riches had made no man poorer, and few begrudged him his success.

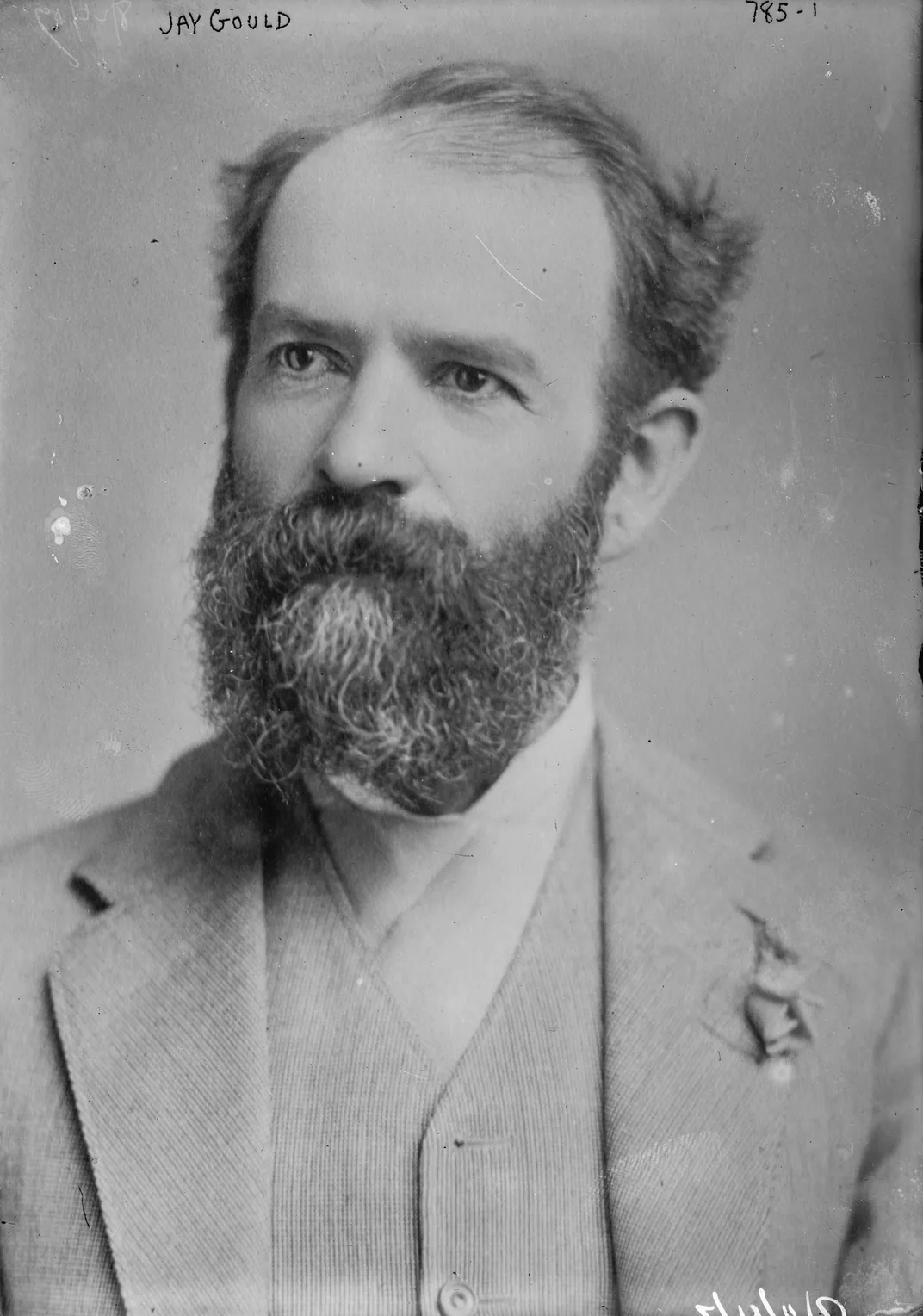

But in part because of his likability and unsullied reputation, John Mackay is mostly forgotten today. In contrast to titans of industry like Andrew Carnegie or railroad magnate and telegraph cable monopolist Jay Gould, who Mackay would famously defeat, Mackay commanded the admiration of people worldwide. The headlines he made generally glowed with admiration, he never abused the public’s trust, his personal style remained unostentatious, and he kept his many philanthropic endeavors quiet.

The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West

The rags-to-riches American frontier tale of an Irish immigrant who outwits, outworks, and outmaneuvers thousands of rivals to take control of Nevada’s Comstock Lode—the rich body of gold and silver so immensely valuable that it changed the destiny of the United States.

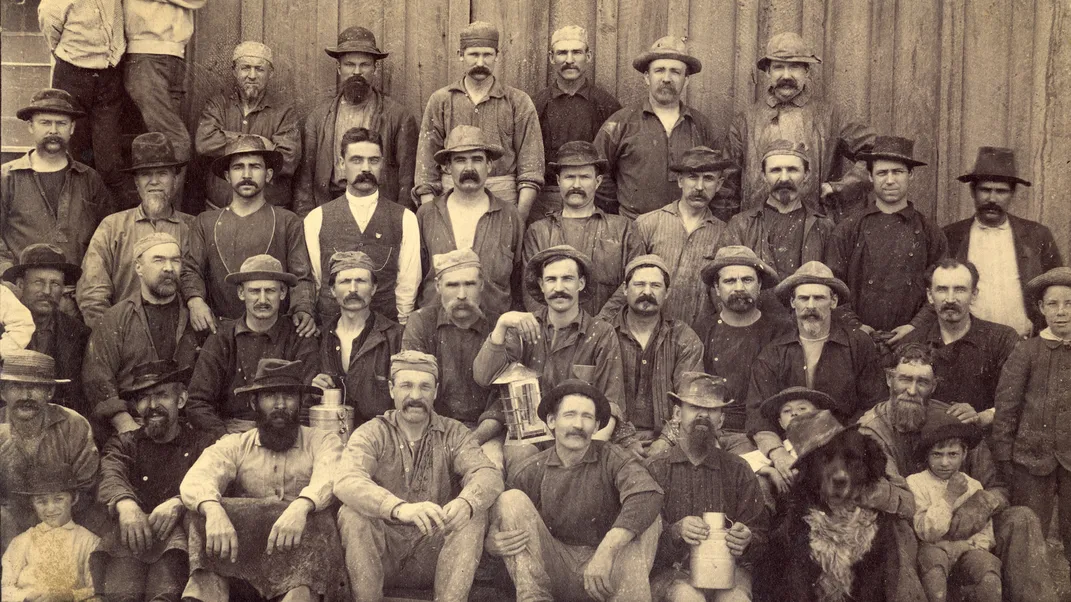

During the California Gold Rush, Mackay mined for eight years without ever making “a raise,” as miners termed a big strike, but he enjoyed the rough, outdoor existence and the companionships of his fellows without the complications and responsibilities of later years. He also worked as hard as humanly possible—in later years, a man who worked alongside him in the diggings said, “Mackay worked like the devil and made me work the same way.”

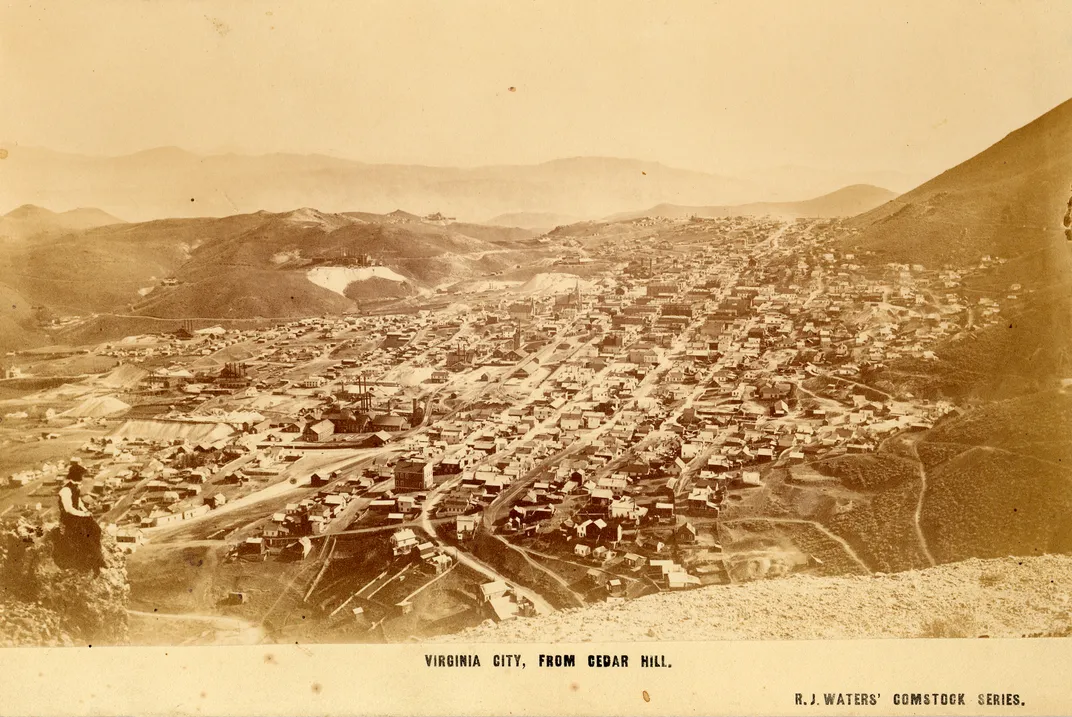

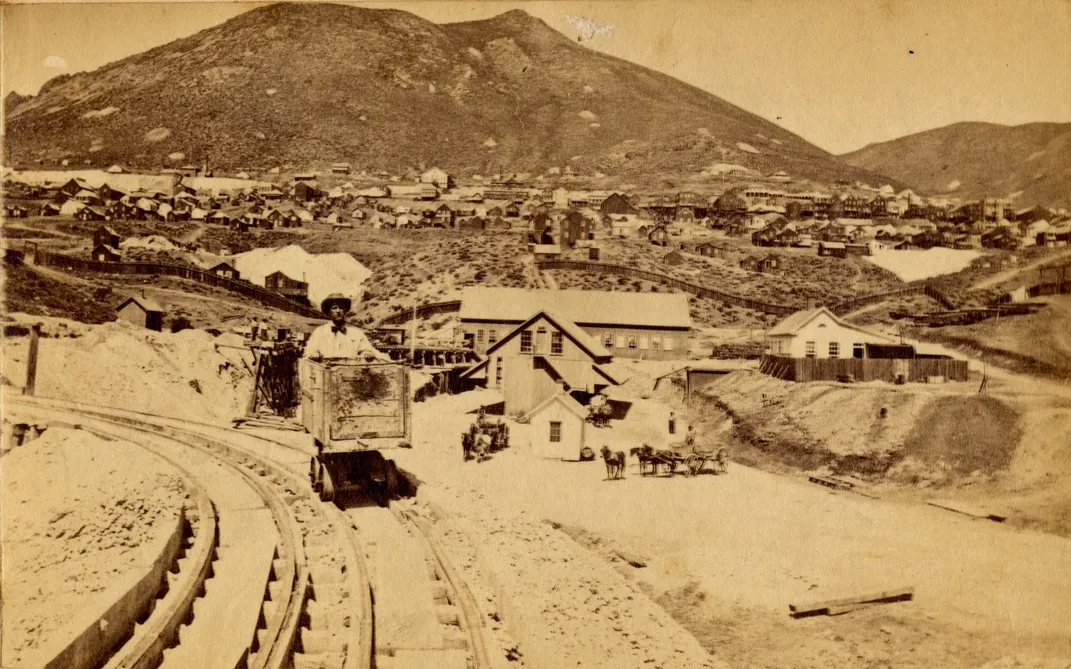

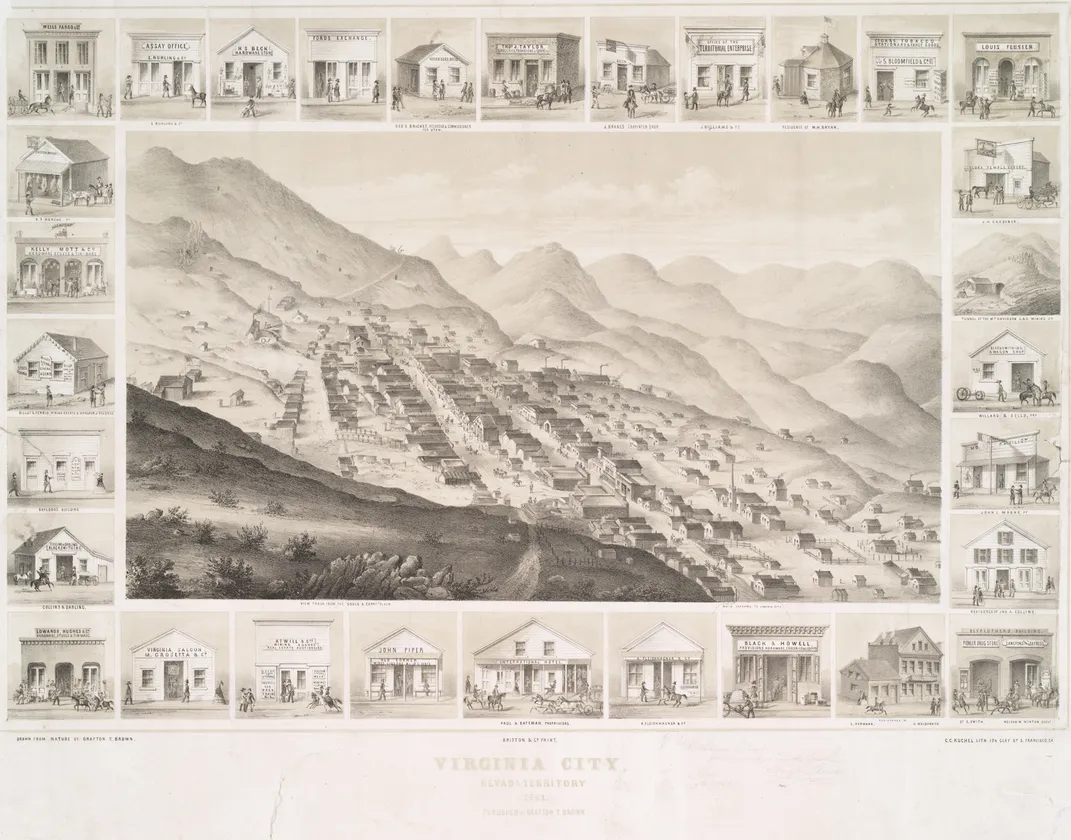

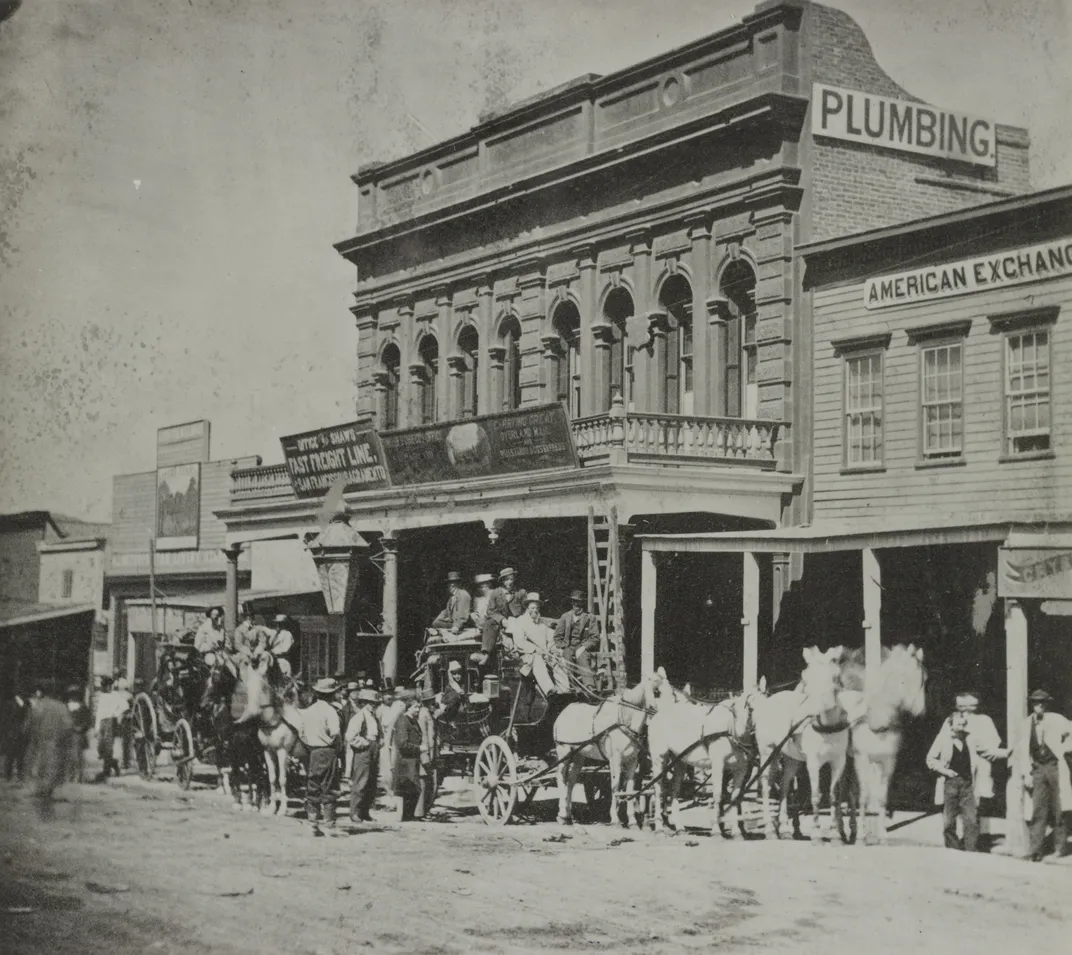

He didn’t have a nickel to his name when he arrived on what soon became known as the Comstock Lode in what was then the western Utah Territory (present day Nevada), so he did what he’d always done—he pushed up his sleeves and went to work. He started as a common hand in somebody else’s mine at $4 per day. Over the next several years, he worked his way up from nothing, doing what any other man would have considered two full days of hard labor crammed into every single day, working one full shift for the $4 he needed to survive and another in exchange for “feet,” meaning a share in the mine’s ownership, for each mine was divided up into so-many “feet” on the lode, and each foot represented one share.

He gradually gained ownership of better and better mining ground and in 1865 emerged as one of the majority owners of a previously obscure mine called the Kentuck, which owned a miniscule sliver of the Comstock Lode between two much larger mines. In the last half of that year, Mackay invested all the money he’d amassed in six years of brutal labor and every penny he could borrow on prospecting the Kentuck far below the surface. For six months he didn’t find a single ton of profitable ore. By the end of the year, Mackay was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, but on New Year’s Day, 1866, he and his small workforce hacked into a ten-foot wide mass of reddish, sugary, gold- and silver-infused quartz at the bottom of the Kentuck’s mineshaft, 250 feet below the surface.

Over the next two years, Mackay mined more than $1.6 million worth of gold and silver from the tiny Kentuck (a sum that in those days had an emotional impact roughly equivalent to $375 million modern dollars). During that time, the Kentuck paid $592,000 to its stockholders, a 37 percent yield – a substantial portion of which went straight into Mackay’s pocket.

Years later, when the New York World asked him if wealth had brought him happiness, Mackay seemed incredulous at the question. He said that it hadn’t. He told the reporter that he’d been happy selling newspapers on the streets of New York as a child and working as an apprentice carpenter in a shipyard before going West, and that he’d been happy hefting a pick and shovel in the California gold country and installing timbers as a hand in the Comstock mines.

Nevertheless, he did confess that nothing but his sons had brought him the satisfaction of watching the Kentuck strike blossom into a genuine Comstock bonanza.

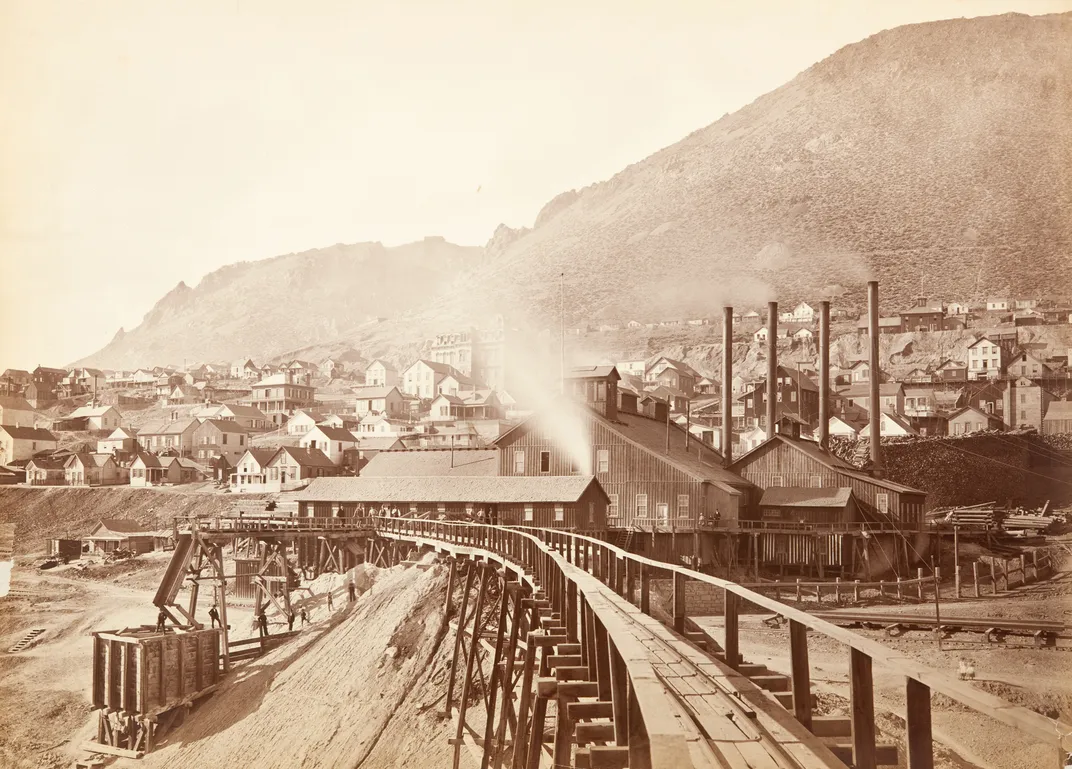

Mackay had made a phenomenal amount of money, but it didn’t sate his appetite for mining—or for speculating in mines. After two other mining ventures, one an expensive failure and the other modestly profitable, Mackay’s biggest mining success came in 1874 and 1875, when he and his partners hit “the Big Bonanza” – a strike 1,500 feet below the surface in the Comstock’s adjacent Consolidated Virginia and California mines. That ore body still holds the record as the most concentrated in history and it made John Mackay one of the wealthiest men in the world. His share of profits ran to between $20 and $25 million, around $50 billion when measured as a similar share of the GDP of the modern United States.

At the peak of the Comstock’s “Bonanza Times” in 1876, John Mackay’s cash income—from the dividends of the two bonanza mines alone—exceeded $450,000 per month. The only people in the world with a monthly cash income anywhere comparable were Mackay’s three junior partners. Their company, The Bonanza Firm, with an aggregate cash income running between $1.2 and $1.5 million per month, was, according to the Spirit of the Times, “The wealthiest firm in America and prospectively the richest in the world.” The income and expenditures of the four-person firm exceeded those of half the states in the Union.

One day, an old mining partner from California Gold Rush days teasingly reminded Mackay that he’d once thrown down his tools in frustration and announced that he’d be content for the rest of his life with $25,000.

“W-w-well,” Mackay stammered, struggling to overcome the stutter that had dogged him since childhood, “I’ve ch-ch-changed my mind.”

**********

Beyond the difficult, dirty, and phenomenally dangerous world of underground mining, Mackay made a name for himself in other areas of business. He shattered Gould’s transatlantic telegraph monopoly, which made Mackay a major player in the communications industry. His last great endeavor came in the attempt to lay a telegraph cable across the floor of the mighty Pacific Ocean to connect San Francisco with America’s recently acquired foreign interests in Hawaii and the Philippines.

A firm believer in the power of private enterprise, Mackay announced that he’d do it without any government “subsidy or guarantee.” Even then, it took more than a year to get government approval and even longer to get the navy to part with its depth soundings of the Pacific. Long before he received formal government approval, Mackay was building 136 miles of undersea cable per month, at tremendous cost. The goal re-energized the old miner, and when Mackay met a friend in May 1902, Mackay put up his fists and sparred a round of shadow boxing, saying that he felt as if he “could handle any 70-year-old fellow in the world.”

But it was not to be. John Mackay died later that year with his wife and a Catholic priest at his side. His son Clarence completed the job of laying the Pacific cable, which greatly extended the reach of American power. At the time of his death, newspapers estimated Mackay’s wealth at between $50 million and $100 million (equal to a fortune of between $50 and $80 billion today), making him one of the world’s richest men.

In the aftermath of Mackay’s death, long, laudatory obituaries filled the columns of most American newspapers—and many in England and France. The Salt Lake City Tribune said that “of all the millionaires of this country, no one was more thoroughly American than Mr. Mackay, and no one among them derived his fortune more legitimately.” The contemporary Goodwin’s Weekly considered Mackay’s example, “the highest of all rich men in America.” He’d “stormed the strongholds where nature had stored her treasures and won them in fair fight” without the taint of profit made in business transactions.

It would fall to a later age of historians and activists to take the mining industry to task for the tremendous environmental devastation wreaked on the American landscape and for the suffering inflicted on Native American cultures. Mining rushes from the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the Black Hills and from Montana to New Mexico dispossessed native tribes of their ancestral homelands. Unrestrained greed denuded forests to shore mine galleries and fire the boilers that powered the hoists and mills, which also dumped tens of thousands of tons of mercury into western rivers and left a legacy of Superfund sites throughout the West.

John Mackay’s popularity may ironically be the reason he has faded from public memory. Mackay died a widely admired man—although he stood among the leading industrialists and mining magnates in the last decades of the 19th century in terms of his wealth, none of the vitriol directed at the “Robber Barons” of the age accrued to John Mackay.

Indeed, in the telegraph business, Mackay kept wages high and incentivized and aided in his employees’ purchase of company stock, one of the first business leaders to take such steps. Mackay’s personal philanthropies through his last decades were legion and legendary, but unorganized. Unlike many of his pocketbook peers, such as Rockefeller, Carnegie, Stanford, and Huntington, Mackay felt no great compulsion to leave behind a philanthropic organization or a university that would spend the next hundred years rehabilitating his family name. He’d never lost it. When Mackay finally did set an old friend to investigating options it was too late, too little time remained to him to push the plan to completion before his death, and his simple will contained no specific provisions or instructions.

In remembrance of his father, Mackay’s son Clarence endowed the Mackay School of Mines at the University of Nevada, Reno. Having his name attached to one of the world’s leading mining institutions would surely fill John Mackay with satisfaction and pride. Being forced to abandon school at age 11 and work to support his mother and sister by his father’s death was Mackay’s greatest regret. In 1908, Gutzon Borghlum—the man who would sculpt Mount Rushmore—erected a statue of Mackay in front of the school, where it remains today. John William Mackay stands as a simple miner with the bottoms of his trousers tucked into a pair of mucker’s boots, holding a chunk of ore in his right hand and resting his left on the handle of a pickaxe. The likeness memorializes John Mackay as he would surely want to be remembered, with his gaze turned toward Virginia City and the Comstock Lode and his sleeves rolled up, ready for work.

From The Bonanza King by Gregory Crouch. Copyright © 2018 by Gregory Crouch. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.