The Teddy Bear Was Once Seen as a Dangerous Influence on Young Children

Inspired by a moment of empathy from President Theodore Roosevelt, the huggable toy had a rocky start before it became the stuff of legend

:focal(1050x750:1051x751)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3a/d3/3ad3165a-0bc4-43d5-9082-a841e2446716/nmah-93-7204.jpg)

A true history of the teddy bear begins in the American wilderness. In November 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt embarked on a hunting trip in Mississippi with one main goal: to bag a black bear. As the tale goes, after Roosevelt had scoured the brush for several days without so much as spotting one, some of his hunting companions corralled an injured old bear and tied it to a willow tree. Here, they said, was Roosevelt’s opportunity to slay one and declare victory. Horrified, the president refused, saying it would be unseemly—unsporting!—for a man of honor to kill this vulnerable creature. He ordered the decrepit bear to be euthanized, and this odd show of mercy quickly became news.

Editorial cartoonist Clifford K. Berryman captured the scene in several Washington Post drawings—one showing a thin Roosevelt refusing to kill a bear, another picturing a more realistically stocky Roosevelt near a smaller bear with a wide-eyed, babylike face. To Brooklyn candy store owner Morris Michtom, the cute cub from the cartoons also looked like a marketing opportunity. He asked his wife, Rose, to sew a stuffed version, and that single prototype sold shortly after the couple placed it in the store window. Rose made more, and with demand exceeding what busy fingers could create, the two began factory production in 1903. Michtom called his cushy new companions “Teddy’s bears,” after the president. By late 1906, the name had shifted to “teddy bear.”

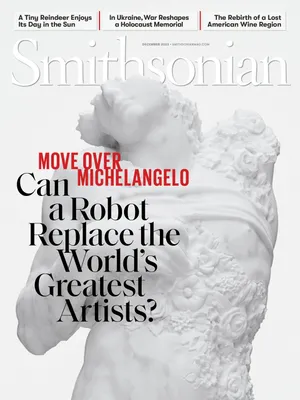

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a1/f7/a1f7cec6-898d-497e-aa1e-e659e7526f52/dec2023_h08_prologue.jpg)

At about the same time, the Steiff company of Giengen, Germany, was coincidentally creating a bear of its own. In 1903, Steiff sold 3,000 of the critters to a New York department store. A year later, Roosevelt, who couldn’t abide the nickname “Teddy” (he had once called it an “outrageous impertinence”), nevertheless deployed his lovable namesake as a mascot in his re-election campaign, prominently displaying a Michtom bear at the White House. That helped propel the animal to further fame: In 1906, one Manhattan store sold more than 60,000, and soon even the German maker Steiff adopted the American “teddy bear” name.

Not everyone was enthralled, though. A few social commentators saw teddy bears as ominous: They feared that some girls’ preference for soft animals over humanlike dolls would become all-consuming, replacing the female urge to nurture babies—and eventually lead to childless marriages. In 1907, the Rev. Michael G. Esper of Michigan warned his congregation that “the fad for supplanting the good old dolls of our childhood with the horrible monstrosity known as the teddy bear” would lead to falling birthrates. The issue roiled the country, though most did not share Esper’s paranoia. A few days after Esper’s tirade, Nevada’s Reno Evening Gazette ran a piece with the headline “Teddy Bears Rule Supreme,” in which a local woman rebuts Esper: “The teddy bear is only a fad, and I do not believe that it is at all harmful for children to play with them.”

The nation seemed to agree, at a time when a more “tolerant, permissive view of childhood” was emerging, says Gary Cross, a historian at Pennsylvania State University and author of Kids’ Stuff: Toys and the Changing World of American Childhood. There was, Cross says, a new “willingness to let children remain childlike for a longer period of time.” Notably, teddy bears helped launch and feed a growing demand for children’s goods—a largely new market in the early 20th century, when child labor was declining.

In the next few decades, bears became a source of comfort during turbulent times—even for those long past childhood. Soldiers carried their own teddy bears, tucked into knapsacks, during both world wars.

The bears soon found a welcoming habitat in literature and pop culture. In 1921, English author A.A. Milne gave his 1-year-old son a fluffy pal who went on to become the world’s most famous bear, because he did what every child wanted from their toys: He came to life! After Milne wrote the Winnie-the-Pooh series, his American publisher, E.P. Dutton, sent the stuffed Pooh on a tour through the U.S. And in 1957, when Elvis Presley performed “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear” in the film Loving You, fans expressed their admiration by sending him thousands of stuffed bears.

More than a century after their debut, collectors are still bullish on the bears. In November 2022, a 1906 Steiff bear sold for £10,500 (around $12,746), a number that did not approach the Steiff Louis Vuitton teddy bear (outfitted in a beret and trench coat with the designer’s signature logo) sold in 2000 for $182,550, which still holds the Guinness World Record for a teddy bear sale. The Ideal Toy Company, which the Michtoms founded in 1903, at one point became the biggest dollmaker in the U.S. To mark the bear’s 60th birthday in 1963, the Michtoms’ son, Benjamin, presented an original bear to Roosevelt’s grandson, Kermit. Though Kermit intended to donate the critter to the Smithsonian, his children had other plans. “They didn’t want to part with it yet,” his wife, Mary Roosevelt, confessed. After the children relented a year later, the historic toy finally made it to the National Museum of American History, where it still resides, a reminder of a child’s innocence—and a president’s sportsmanship.

Home Games

Simple toys from past millennia evoke humanity’s undying urge to play

by Jaimie Seaton

Lance Encounter

Germany, Middle Pleistocene, c. 300,000 B.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f1/98/f198b74f-97de-49b8-81c7-77a827fadcbc/journalpone0287719.jpg)

In the 1990s, archaeologists in Schöningen, Germany, discovered the earliest large-scale record of tools made by Middle Pleistocene humans, including a 30-inch double-pointed lightweight curved stick that was shaped and smoothed into an aerodynamic tool. Archaeologists believe that children in the Middle Pleistocene played with these pointed sticks and thereby developed throwing and hunting skills. In support of this theory, researchers have also noted that in later periods, children in far-flung countries like Chad and Indonesia once played with similar implements.

Motion Pictures

Ice Age Europe, 16,000-9,000 B.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/66/f0/66f0a715-ac56-4009-8a00-ec9ebf527eab/movie.jpg)

The Upper Paleolithic version of flipbooks, rondelles are small disks made of bone, antler or ivory, with an image carved on either side and one or two holes for a cord in the middle. Tug the cord back and forth, and the disk swings, giving the illusion of a moving image. One ice age example found in France in 1868 shows a doe with her legs tucked under her on one side and extended on the other, so it looks like she is running when the rondelle is swinging.

Doll in the Family

Roman Empire, c. A.D. 1 to 400

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ce/8f/ce8fd503-53fc-4525-bdb0-2c77856fb972/doll.jpg)

Since the 1800s, archaeologists have excavated more than 500 doll-like figures from the Roman world. Scholars long thought these were principally used as burial objects, but the extensive wear on the jointed limbs has led archaeologists in recent years to conclude that children did indeed play with these dolls. Toy figures representing adult women were made of ivory or bone, and some even had miniature jewelry and intricately carved hairstyles.

Gift Horse

Egypt, 250 B.C. to A.D. 500

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4a/73/4a73e557-8413-4b21-984f-163ce09d77df/dec2023_h09_prologue.jpg)

Correction, January 30, 2024: A previous version of this story misidentified Kermit Roosevelt Jr.’s wife; she was Mary Roosevelt.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)