OFFICE OF ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND INTERNSHIPS

Science, Policy, and Pandemics

For years, the dangerous virus currently making global headlines was circulating in wild animals, replicating and spreading with little notice from the host that carried it. This virus, that scientists now believe originated in bats, quickly turned from a benign hitchhiker to a deadly producer of disease when it was introduced to an animal population it had never come in contact with before – humans.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Dr._Suzan_Murray.jpg)

For years, the dangerous virus currently making global headlines was circulating in wild animals, replicating and spreading with little notice from the host that carried it. This virus, that scientists now believe originated in bats, quickly turned from a benign hitchhiker to a deadly producer of disease when it was introduced to an animal population it had never come in contact with before – humans.

The now-named Sars-CoV-2, a coronavirus causing the severe and sometimes deadly disease COVID-19, has caused an outbreak of pandemic proportions. The virus has infected over 3 million and killed 238,628 people worldwide (WHO Situation Report – 104, May 3, 2020), changing life as we know it around the globe.

While the COVID-19 pandemic may have come as a total surprise to many, to those in the field of Global Health, an outbreak of this proportion was just a matter of time. Smithsonian scientists have been studying zoonotic disease emergence and evolution for decades. Anthropologists at the National Museum of Natural History have worked to build a better understanding of the nature of past epidemics while researcher’s with Smithsonian’s Global Health Program have been investigating where dangerous diseases are circulating in animal populations and how to best prevent disease spillover into humans with their work in a global partnership called PREDICT.

In light of the current pandemic, our scientists are looking even more fervently toward the future of pandemic prevention and are offering that expertise to Congress.

COVID-19 - A CASE STUDY IN SCIENCE COMMUNICATION

Nestled on the third floor of the Smithsonian Castle lies a small but influential office that acts as Smithsonian’s face in front of the US Government - the Office of Government Relations. This liaison between the Smithsonian and Congress coordinates efforts to connect Smithsonian experts with the policymakers who keep our museums and research centers up and running. When COVID-19 began making headlines, it became clear the time had come to connect our global health researchers with Capitol Hill.

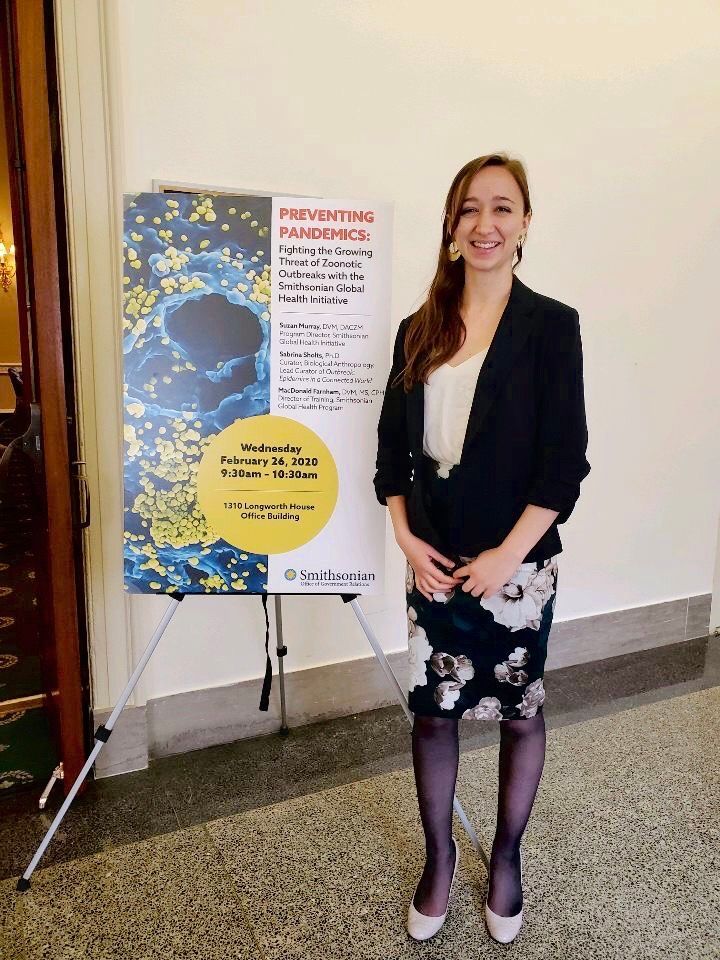

In February 2020, just as the first cases of the virus were being reported in the United States, three of our researchers presented on Capitol Hill at our “Preventing Pandemics” briefing. The researchers spoke about the importance of a One Health framework for tackling global health challenges. One Health takes into account the interconnectedness between human health, animal health, and environmental health. In doing so it works to understand the mechanisms behind disease emergence - including environmental degradation and human behavior - and how to best prevent it.

At the briefing, Dr. Sabrina Sholts, lead curator of the Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World exhibit at the National Museum of Natural History, spoke on the importance of Smithsonian’s collections. The museum collections have been used to research the origins and evolution of viruses like the one that caused the 1918 influenza pandemic and the Zika outbreak in 2015.

Sholts also spoke to the importance of the Outbreak exhibit as an educational tool for showing how urbanization, global travel, and human population increase influence how diseases emerge and spread. The exhibit has been made available to governments across the globe through Outbreak DiY, where the information can be easily translated and printed for display.

To represent Smithsonian’s Global Health Program, Program Director Dr. Suzan Murray and Director of Training Dr. Mac Farnham, spoke about Smithsonian’s contribution to pandemic prevention through a multi-agency collaboration - the PREDICT Program. A piece of the larger USAID Emerging Pandemic Threats Program, PREDICT worked in over 30 countries to establish a network of zoonotic disease monitoring.

A GLOBAL HEALTH PARTNERSHIP

For the last decade, the PREDICT program has stationed researchers with the Smithsonian Global Health Program in Kenya and Myanmar to identify new diseases, to train locals in disease surveillance, and to educate locals about the viral dangers lurking in wild animal populations.

Pathogens that are dangerous to humans circulate in animal populations constantly. These pathogens become a potential risk to humans at the intersection of wildlife, livestock, and human health. As human populations grow and encroach on wild spaces - coming in more frequent contact with novel pathogens - the threat of a spillover event becomes more potent, making disease surveillance essential. By tracking potentially dangerous diseases in wild animal populations, humans can identify diseases, change risky behaviors, and better prepare for pandemics by having crucial information ready and at hand.

To prevent these particularly dangerous viruses from jumping to humans, researchers have been working to identify a few key factors. Using data modeling techniques, scientists identified 5 different viral families (one of which being coronaviruses) that have been the focus of this surveillance effort due to their heightened risk to humans. Next, the modelers used in-country data on wildlife biodiversity, urbanization, human behavior, and other factors to define “Hot Spots”, or areas where spillovers are most likely to occur. The PREDICT partners then started setting up shop in these Hot Spots, building over 60 labs, training over 6000 people, and sampling over 160K people and animals to search for novel pathogens.

During the program’s 10 year run, they identified over 1200 new mammalian viruses, 161 of which are coronaviruses. While the funding for the PREDICT project was not renewed in 2019, scientists are now working to direct some stimulus funding to programs that study viruses at the human-animal interface.

Continuing the Cause

Sharing the discoveries of the PREDICT program and the work done by Smithsonian researchers on Capitol Hill has allowed our scientists to have a seat in front of Congress at this important time.

As a result of this communication effort, the House Science Subcommittee called upon Dr. Murray as an expert witness for the committee’s hearing, Coronaviruses: understanding the Spread of Infectious Diseases and Mobilizing Innovative Solutions, that occurred in March. This provided an opportunity to showcase the important discoveries the Smithsonian’s Global Health Program has made and allowed Dr. Murray to highlight why this work needs to continue.

“Understanding the current viral threats, the patterns and drivers of disease emergence, and the human behaviors that contribute to such emergence will best allow us to not only respond to this outbreak but the next one and the one following that, because we know this is coming,” stated Murray in her testimony.

Involving our scientists in these kinds of endeavors opens the doors for the Smithsonian to provide its expertise in times of need. The Office of Government Relations is constantly working to ensure the Smithsonian has the support it needs to continue its ground-breaking research programs and exemplify our mission of the Increase and Diffusion of Knowledge. In the realm of global health, the Office of Government Relations is continuing to provide essential information about this pandemic to their colleagues on the Hill and, in turn, are garnering support for Smithsonian’s research in this field.