NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Six Avatar-Themed Items in the Smithsonian Collections

Check out six specimens and artifacts in our collection that are similar to fictional objects in “Avatar: The Last Airbender.”

:focal(640x352:641x353)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Collage-6-items-final22-crop.jpg)

When Netflix released “Avatar: The Last Airbender” in May, the animated show became a summer hit instantly. Avatar memes circled social media, those who hadn’t seen it when it first aired 15 years ago watched it for the first time and one TikTok user even started writing viral songs for a musical version of the show.

If you haven’t seen it, the show takes place in a fictional world made up of four nations: The Water Tribe, Fire Nation, Earth Kingdom and Air Nomads. In each nation live “benders” — or people with the ability to control one of the elements. But one person, called the Avatar, has the ability to control all the elements and he went missing for 100 years.

The show begins as Water Tribe siblings Katara and Sokka find a boy frozen in a block of ice, and discover he’s the Avatar, Aang. Aang discovers that the peace he had known a century ago had been disturbed because the Fire Nation had attacked the others, in hopes of colonizing the world. Now Aang, Katara, Sokka and others they meet along the way must fight back against the Fire Nation before it’s too late.

The world of “Avatar” is filled with fictitious (and some real) animals and objects. Here are six specimens and artifacts in our collection that are similar to fictional objects in the show.

Meteorite knife

While infiltrating the Fire Nation, Sokka takes lessons from a master swordsman and ends up forging his sword from a meteorite that had fallen earlier in the episode. The sword had a dark color and an ability to cut through metal easily. He affectionately called it his “space sword.”

Though it’s far smaller than Sokka’s, the Smithsonian has its own blade forged from a meteorite. The knife was made in Mexico out of a meteorite called Casas Grandes. If you look closely, you can see the Widmanstätten pattern on the blade, a unique criss-crossing crystal structure often found in iron meteorites.

Wood frogs

At one point in the show, Katara and Sokka get sick and Aang must search for medicine for them. He visits an Earth Kingdom herbalist who tells him he needs to find frozen wood frogs for the pair to suck on. In the show, the frozen frogs’ skin secretes a medicinal substance that will cure their sickness. Aang grabs a few frogs from a nearby swamp, but he’s captured by the Fire Nation, and the frogs start to thaw and hop away. Luckily, Aang escapes and grabs more frozen wood frogs on the way back to his friends.

While real wood frogs don’t secrete medicine, they can freeze during winter and thaw out when temperatures rise. When the temperature drops below freezing, these frogs stop breathing, their hearts stop beating and water inside their body actually turns to ice. To keep from dying, they produce homemade antifreeze within their bodies by mixing glucose and urea. They can survive in temperatures down to 3 degrees Fahrenheit this way.

Fireflies

At another point in the show, Sokka uses a lantern given to him by a mechanic to explore underground. He complains that he can’t see very well and opens up his lantern to find that fireflies are illuminating it. One flies out, producing a steady, but dim, bluish green color. He asks why fireflies are used instead of a flame, and the mechanic replies that they’re a nonflammable light source — the room they were outside of was filled with natural gas and he had accidentally created an explosion before.

The Smithsonian has 447 species of fireflies in its collection. In total, there are about 2,000 firefly species worldwide. Fireflies produce bioluminescence by combining the chemical luciferin with the enzyme luciferase, oxygen, calcium and adenosine triphosphate (ATP). They are considered “cold lights” because they don’t create a lot of heat when they glow.

One species, called the blue ghost firefly — or Phausis reticulata — does produce a steady, bluish-greenish light like the fireflies in the show. Blue ghosts can remain aglow for up to a minute at a time and are found in the southern Appalachian Mountains.

Clams

Though there aren’t many invertebrates in the world of Avatar, the group did encounter some clams while looking for food in a Fire Nation fishing village. The clams for sale oozed brown sludge, and the team discovered that the village was suffering because the army had built a factory that was polluting their water.

Interestingly, real clams are important bioindicators, or organisms that can serve as proxies to better understand overall ecosystem health. “Clam” is a generic term, referring to animals in the class Bivalvia, which includes other animals like mussels and oysters. Most bivalves are known as “filter feeders,” because they suck in water through their gills, filter food particles out from it and release the water back out again. But while they trap food, they also trap toxins and pollutants, which build up in their tissues. Scientists examine these tissues to learn more about pollution in certain bodies of water.

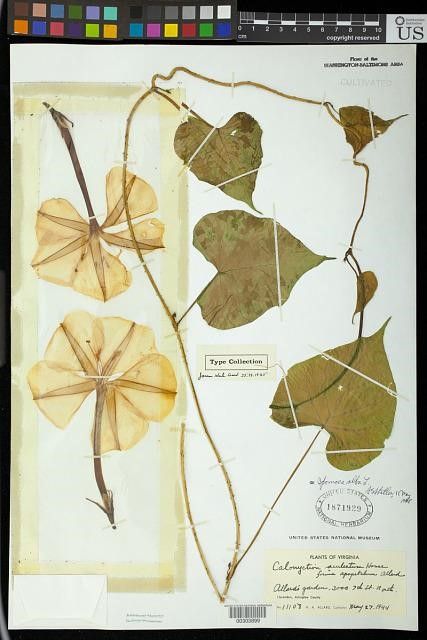

Moonflowers

In the show, the moonflower is white and star shaped. It makes a quick appearance in the Earth Kingdom city of Ba Sing Se, where it’s shown wilting in a vase sitting in direct sunlight. When it’s pushed back into the shade, it perks up immediately.

Moonflowers are a real group of plants that have night-blooming flowers, including the tropical white morning-glory. This is because these flowers have evolved over millions of years alongside pollinators that are active at night. The tropical white morning-glory, or Ipomoea alba, is a climbing vine that is pollinated by sphinx moths. It blooms from July to October and, in the summertime, the flowers can take only a few minutes to open. This plant is found in warmer climates, including the southern United States and Central America.

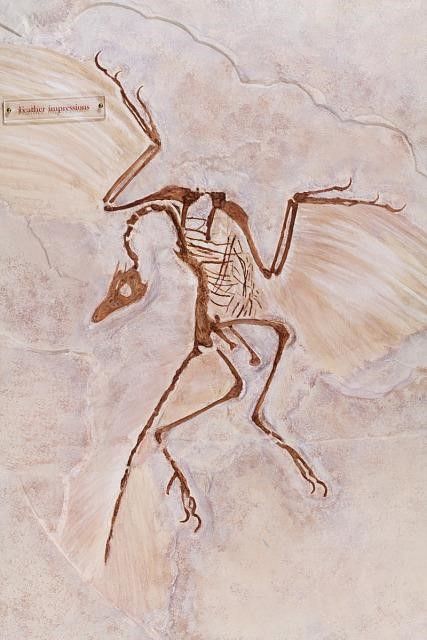

Archaeopteryx

The iguana parrot is a creature that sits on the shoulder of a pirate that the group encounters, and it attacks Momo, the flying lemur that travels with the group. Many of the fictional animals in the world of Avatar are crosses between two completely different species — like a catagator or a turtle seal. But the iguana parrot is interesting because a bird-reptile cross actually existed, the extinct Archaeopteryx.

The Archaeopteryx lived in the Jurassic period, and though there was some debate, most researchers consider it the oldest known bird. It has been called the link between reptiles and birds, but recent discoveries of bird-like dinosaurs from China might soon make it difficult to draw a sharp line between what makes a dinosaur versus what makes a bird.

Like the iguana parrot, the Archaeopteryx could fly, but based on the absence of a keeled breastbone, it was probably not an efficient flapping flyer. The Archaeopteryx also had claws independent of its wings similar to the iguana parrot. The Smithsonian has casts of the Archaeopteryx specimens at the Natural History Museum in London and the one at Berlin’s Museum für Naturkunde.

Related Stories:

Six Bewitching Smithsonian Specimens to Get You Ready for Halloween

Why Science Needs Art

Check Out These Unexpected Connections in Natural and Presidential History