NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Countdown to the New Year: 7 of Our Favorite Discoveries from 2017

To count down to the new year, here are some of our favorite stories about the exciting discoveries our researchers made this year.

:focal(2172x1656:2173x1657)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/nmnh_collage_2.jpg)

2017 was filled with exhibition openings, exciting announcements, and plenty of new discoveries. Our researchers traveled the world and shared some of their latest findings with us. This research goes beyond describing something new – it often has impactful implications that change the way we see and understand our natural world. To count down to the new year, here are some of our favorite stories about the exciting discoveries our researchers made this year.

1. Acanthurus albimento

This year, our researchers made some exciting discoveries in some of the most unexpected places. During an extensive fish-market survey in the Philippines, our Fishes collections manager Jeffrey Williams and colleagues described a new species of surgeonfish. Acanthurus albimento is vibrantly colored. It is in the genus Acanthurus, which has been closely studied by scientists for decades – making the discovery of multiple specimens of this new species quite surprising!

2. Cyrotadactylus lenya and Cyrtodactylus payarhtanensis

Some of the new species discovered by our researchers this year are part of a much larger story. Myanmar is recognized as a biodiversity hotspot, yet it also has one of the highest deforestation rates in the world. The Lenya Banded Bent-toed Gecko (Cyrtodactylus lenya) and the Tenasserim Mountain Bent-toed Gecko (Cyrtodactylus payarhtanensis) have restricted distributions in the vicinity of the proposed Lenya National Park in Myanmar. These species appear to be cave endemic, meaning they are restricted to isolated karst (limestone) outcrops. These two species are significantly different from one another in terms of morphology and genetics, yet they occur within 20 min (33 km) of each other.

George Zug and Dan Mulcahy of our Vertebrate Zoology Division of Amphibians and Reptiles described these new species in a PLOS One article in an attempt to alert the Burmese government and the conservation community to the impacts of the continuing deforestation of the proposed national park.

3. Incadendron esseri

This year, some of our botanists described a new species of plant that stands above the rest – literally. Incadendron esseri is a large canopy tree that it stretches up to 100 feet tall and spans nearly two feet wide in diameter, yet it has gone undetected until now.

Incadendron esseri, described by NMNH research botanist Kenneth Wurdack and William Farfan-Rios, is both a newly described genus and species in the family Euphorbiaceae. The tree is commonly found along an ancient Inca path in Peru, the Trocha Unión. The name Incadendron was chosen as a combination of “Inca” referring to the indigenous Inca empire, and “dendron” (Greek) referring to tree. While Incadendron has a broad range along the Andes, it is susceptible to climate change because it lives in a narrow band of temperatures.

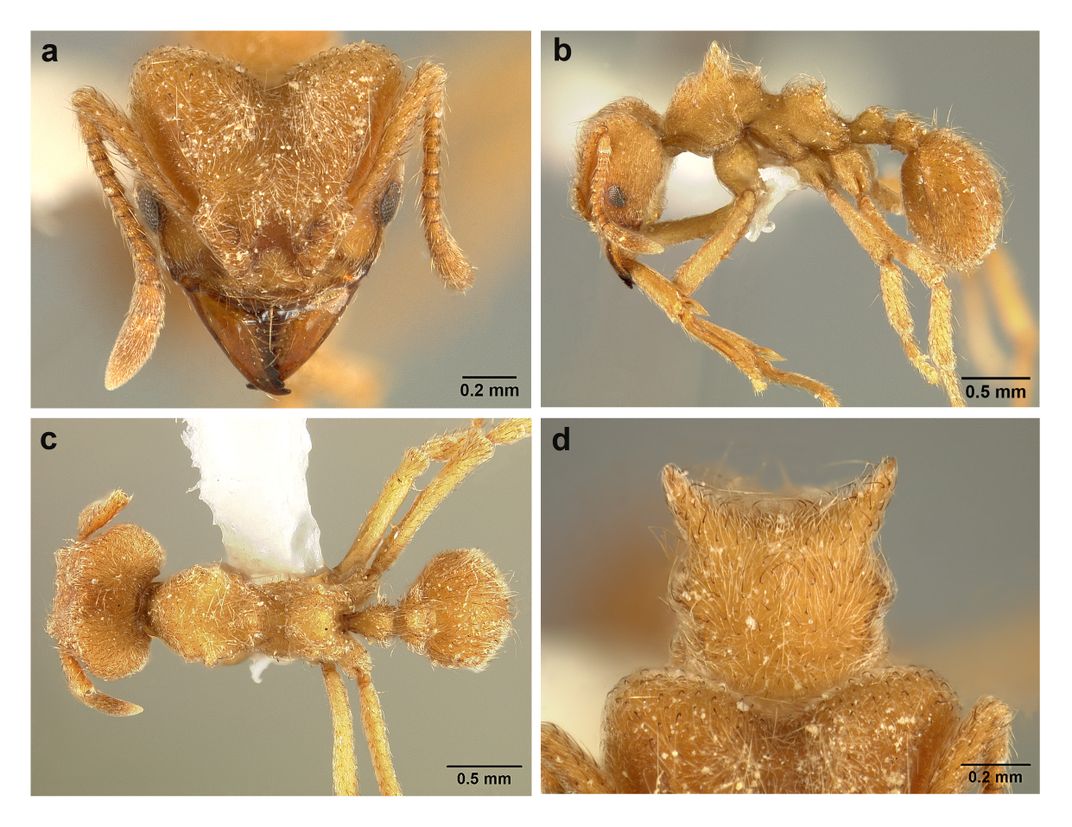

4. Sericomyrmex radioheadi

The countdown of some of our favorite discoveries in 2017 keeps rocking with Sericomyrmex radioheadi. This species of ant is named after the English rock band Radiohead as an acknowledgement of their longstanding efforts in environmental activism and in honor of their music – which is an excellent companion during long hours at the microscope!

Described by NMNH researchers Ana Ješovnik and Ted Schultz, it is for now only known from one locality in Amazonian Venezuela. Using a scanning electron microscope, they found that the bodies of the ants were covered with a white, crystal-like layer. Curiously, this layer is present in female ants (workers and queens), but it is entirely absent from male ants. The chemical composition and function of this layer are unclear, but one possibility it has a role in protecting the ants and the fungus ants grow from parasites.

5. Palatogobius incendius

While we have described a number of new species this year, could invasive species be wiping out biodiversity before scientists discover it? Luke Tornabene and Carole Baldwin, research zoologists in our Vertebrate Zoology department, observed the first reported case of lionfish, an invasive species in the Caribbean, preying upon an unknown fish species living in the reefs of the “twilight zone.”

The new fish, a small goby named Palatogobius incendius, lives at depths (400 ft.) that are largely underexplored. “Once we discovered invasive lionfish — sometimes in huge numbers — inhabiting barely explored deep reefs, our concern was that these voracious predators might be gobbling up biodiversity before scientists even know it exists. This study suggests that they are doing just that,” said Baldwin. The good news for this new species is that when you see one, you typically see 100 or more schooling together. In addition to seeing this species on deep reefs off Curacao, they have been seen while sub diving in the eastern and western Caribbean. So although it’s unknown what the impact of lionfish predation is on the new species, odds are good that it will survive this invasive threat.

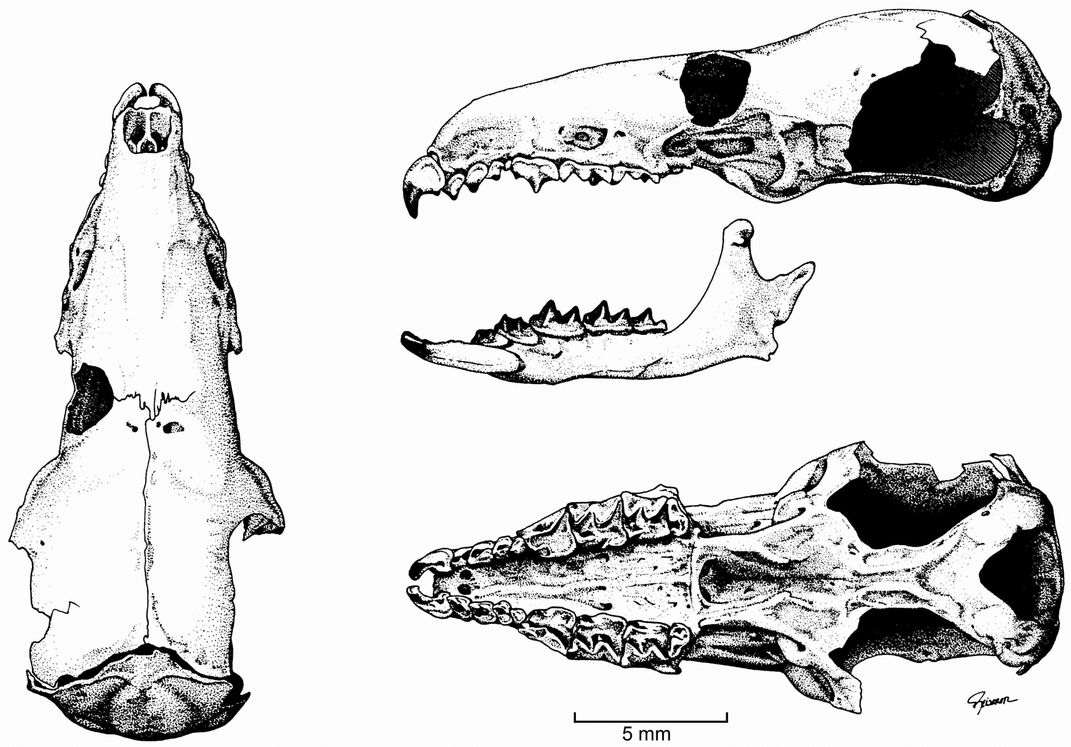

6. Cryptotis monteverdensis

No taming of the shrews this year, but we did name one! Neal Woodman, one of our Mammals curators, along with a colleague from the University of Kansas, described a new species of small-eared shrew (genus Cryptotis) found in Costa Rica. One reason the new species (Cryptotis monteverdensis) is remarkable is that it represents a group of shrews (Cryptotis thomasi group) that otherwise occurs only in mountainous regions of Panama and in the Andes of South America. This species may therefore represent a key to understanding the interchange of mammals along the Central American corridor between North and South American.

A specimen of the new species was first discovered in the 1970s, and the two researchers have spent several decades attempting to locate a population of Cryptotis monteverdensis and learn more about it – to no avail. Although the locality of the first discovery in the Tilarán highlands is known to within a few feet, no additional individuals have ever been located. Was this species a victim of well-documented habitat change in the region? Or, does it survive in some remote corner of the Tilarán Highlands that remain to be surveyed? The researchers still hope to solve this mystery.

7. Ancient Empires

This year we discovered not only new species, but evidence of the incredible natures of ancient empires. For a very long time the ancient empires of Inner Asia were thought of as marginal to the great civilizations of the world. New archaeological research, however, is now documenting the sophistication and independent traditions of the nomadic empires that emerged in Mongolia and surrounding regions around 200 BC. A new publication by NMNH archaeologist Dan Rogers provides evidence for the extensive use of fortified towns and other types of buildings by these early empires. Unlike many other places in the world the growing settlements were not the foundation of the empires, but were built later to support the administrative needs of empires such as the Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries AD.

Here’s to a year of health, happiness, and scientific discovery. Happy New Year!