NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

A Forgotten Olympic First

Taffy Abel, U.S. hockey’s initial American Indian player, won a silver medal at the inaugural Winter Games almost a century ago

:focal(2591x1727:2592x1728)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/d6/b6d642b7-7b96-413a-a3c7-abbe77cab94f/taffy_abel_with_hockey_stick.jpg)

On the eve of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, family and friends of Clarence “Taffy” Abel are seeking overdue recognition of his path-breaking role in the history of the Games and ice hockey. A silver medal winner on the U.S. Olympic team in 1924, Abel was the first American Indian to play in the Winter Games. He was also the first Native player in the National Hockey League (NHL), helping his teams win two Stanley Cup titles.

In 1973, Abel became one of the first players to be inducted into the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame. Yet even recently the NHL seemed unaware of his Native heritage. One reason for this might be that Abel never mentioned it during his professional career.

“Taffy Abel lived in two worlds,” says his nephew George Jones, “the public-facing White world of hockey and the private-facing Chippewa world amongst hometown friends and family.” This “racial passing,” says Jones, was necessary “to escape oppression and discrimination.”

Abel was born on May 28, 1900, in the northern Michigan city of Sault Ste. Marie. His mother, Charlotte Gurnoe Abel, was a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. She, Taffy and her daughter are listed on the 1908 Durant Roll of the Bureau of Indian Affairs as Chippewa. (The Chippewa peoples are now known as Ojibwe.) But they were also U.S. citizens, a status denied at the time to most American Indians. According to Jones, Taffy and his parents downplayed his tribal connection to save him from compulsory enrollment in the region’s Indian boarding school founded by the U.S. government. Instead, Taffy went to the local public high school, where he earned his nickname “Taffy” from his fondness for that treat.

During his playing career, including nine seasons in the nascent NHL, Abel stood out as a U.S.-born citizen in a sport dominated by Canadians, but he was never identified as American Indian. He returned to his Native heritage only after retirement, when in 1939 he organized and coached a Northern Michigan Hockey League team he named the Soo Indians in honor of his recently deceased mother, a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Band of Chippewa Indians. (“Sault” is pronounced “Soo.”)

As a defenseman, Abel left his mark for his intimidating build and “carcass-rattling” style of play. At 6 feet 1 inch and 225 pounds, much larger than most players of the time, he inspired sportswriters to call him things like the “Michigan Mountain.” He thrived as a tough “60-minutes” man, who played entire games without substitution, thick padding or even a helmet. Jones calls these the “primitive” years of hockey (as opposed to the genteel sport of today), and Taffy more than held his own in play that Jones says had a reputation for “borderline criminal behavior.” During the early 1920s, one league official even threatened to ban Abel from the sport for his alleged “ruffianism.”.

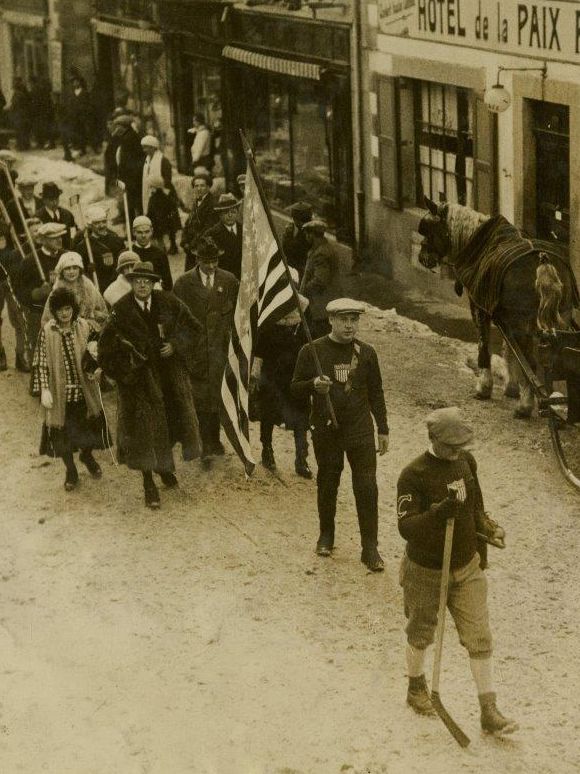

Yet that same official vigorously recruited Abel for the U.S. team in the buildup to the 1924 Winter Olympics in Chamonix, France—the first to be held separately from the summer games. Abel initially declined, as after the death of his father in 1920, he was the only family breadwinner. But a friend lent him travel money, and to Abel’s delight, the sporting goods company A.G. Spalding and Brothers donated all of the team’s equipment. At Chamonix, the entire American team elected Abel to carry the U.S. flag.

The Olympic tournament, says Jones, left European fans “shocked, yet also thrilled, by the furious American style of hockey.” Sportswriters, with their usual understatement, described ice stained “crimson from bloody noses.” The championship, played outdoors without sideboards like pond hockey, matched the two favorites, the United States and Canada, in a “splendid” game. The seasoned Canadian offense, based on an existing amateur team, the Toronto Granites, outscored the United States 6–1. Historic film footage on the official Olympics website shows Taffy carrying the American flag and the championship hockey game.

After Chamonix, Abel followed the example of another great Native athlete, Jim Thorpe, and helped develop the budding professional sports industry. He joined the start-up season of the New York Rangers in 1926, helping his team win the Stanley Cup two years later. In 1929, the last-place Chicago Blackhawks bought his contract and by 1934 also won the Stanley Cup.

After playing 333 games in the NHL, Abel retired and returned to his hometown of Sault Ste. Marie. In addition to coaching and mentoring Native players, he ran a popular café and opened a resort he called Taffy’s Lodge. However, Jones said that when people asked him what he did for a living, he liked to reply, “I’m in the business of winning.”

Recognition for Abel’s role as a breakthrough Indian athlete has come gradually and posthumously. With support from the Salt Ste. Marie Band of Chippewa Indians, he was inducted into the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame in 1989. He was among those the National Museum of the American Indian honored in a roster featured in its 2012 “Native Olympians” exhibition. As attention turns to the 2022 Winter Olympics, his nephew Jones hopes to win widespread awareness of Abel’s achievements by promoting February 4 as Taffy Abel Day.

Read more about Native athletes in American Indian magazine’s “The Creator’s Game: Native People Created Lacrosse Yet Now Strive to Play the Sport in International Arenas” and “The World Eskimo-Indian Olympics: A Friendly Competition of Ear Pulls, Knuckle Hops and Toe Kicks.”