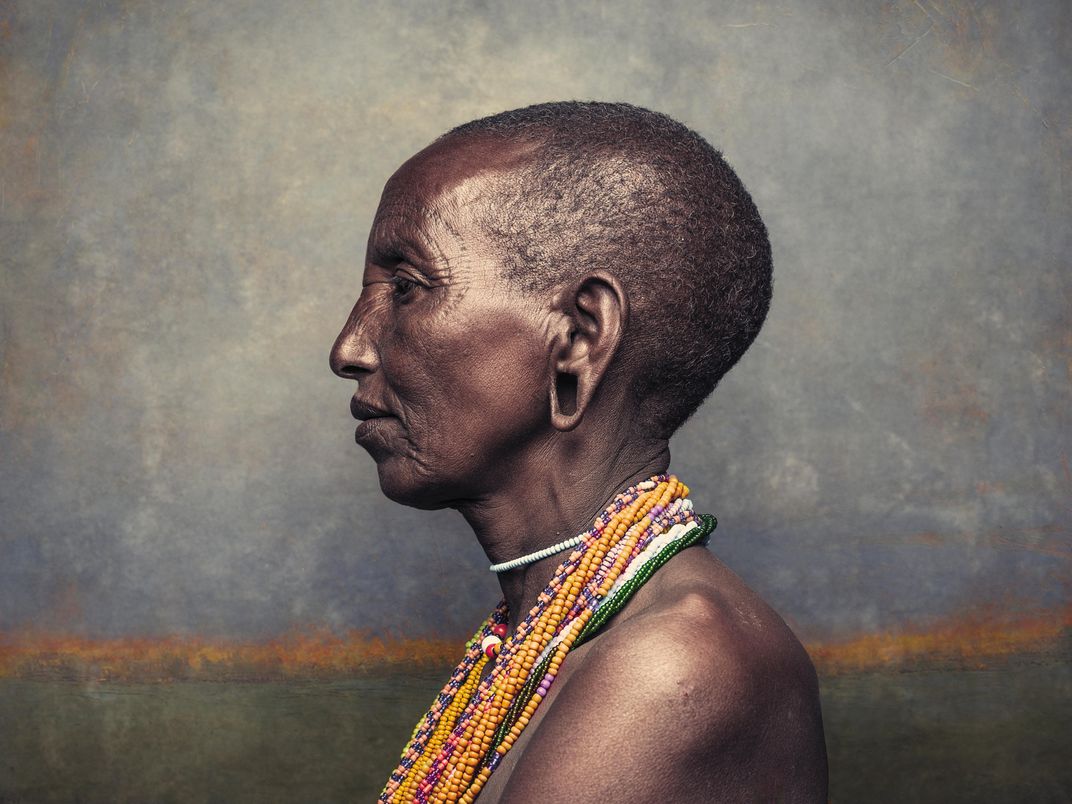

Get Face to Face With the Tribes of Tanzania

As safari parks encroach on their ancestral lands, indigenous groups struggle to maintain their ways of life

There are more than 3,000 tribes on the African continent, but the Hadza of Tanzania are in a category of their own. They’re genetically isolated from most other groups. Their click-based language isn’t closely related to any other tongue. About a quarter of their thousand members still live in the old hunter-gatherer way: collecting berries and digging up tubers, hunting animals with poisoned arrows and moving constantly from camp to camp. Archaeologists believe that people very much like the Hadza have been living on the same land since the Stone Age.

When Christopher Wilson set out to photograph members of this remote tribe, he and his guide had to drive off-road through an expanse of rough, arid land. After wandering on foot, they eventually reached an encampment and set up a makeshift studio right on the spot. Members of the tribe helped hold up his tent.

He had a very different experience photographing two other Tanzanian tribes. The stately, cow-herding Masai were easy to find: They live in established villages near major tourist spots. “We shot their portraits in a cinder-block church,” he says. “The whole village was laughing and looking in through the windows.”

Like the Masai, the Barabaig—the third tribe Wilson photographed—are relative newcomers to the area. Both groups originated in the Nile region and gave up their hunting-gathering ways long ago. Today, they raise livestock and grow their own crops. The wealthiest families own several thousand head of cattle, divided among numerous sons over vast areas. While Hadza men have been described as serial monogamists, the Masai and Barabaig may have as many as ten wives.

All three tribes face existential threats. The Hadza have lost 90 percent of their roaming grounds over the past century, mostly to other tribes. Game reserves have cleared lands where the Masai and Barabaig graze animals. The government recently passed laws forbidding tribes from planting crops near the Ngorongoro Crater, a popular safari destination. Tribal warriors also run into trouble when they attack lions. These kills are forbidden by Tanzanian law, but they earn the men status within their tribes, especially when the beasts are threatening their livestock.

Still, Tanzania’s tribes have more autonomy than most indigenous people, according to a study published this summer. When the data-analysis umbrella group LandMark looked at land rights in 131 countries, Tanzania was one of just five to earn the highest possible score across ten different indicators, including legal recognition, authority over boundaries, and access to wood and water.

That’s largely because Tanzania doesn’t allow private land ownership outside urban areas. Rural property belongs to all citizens in common, and tribes are largely free to negotiate boundaries among themselves. Wilson’s photos depict these groups at a time when they’re still able to live very much as their ancestors did—grazing cattle, hunting for game or moving from camp to camp among the ancient baobab trees.

Related Reads

The Tree Where Man Was Born

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/e9/e9e993c1-ede5-4ecb-8ec3-6b5d34ba6585/oct2016_b06_tanzania.jpg)