Stunning, Surreal Concepts Cast a Spell on the Fairy Tales Architecture Competition

Ukrainian architect Mykhailo Ponomarenko came in first this year for his sci-fi meditation “Last Day”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/49/6549faf5-ec07-4569-b52b-ac99af05ee95/19072_03.jpg)

For millennia, the fairy tale's unique ability to communicate important lessons through the telling of fantastical tales has held audiences in rapture. Now, the architectural community has turned to the tried-and-tested narrative form to provoke new innovations and interest in architecture through the Fairy Tales competition.

Entering its fourth year, the competition was first imagined up in 2013 by architectural thought-leader Blank Space in partnership with the National Building Museum. By its very nature, the competition treats architects as worldbuilders. To participate, entrants must submit original artwork and complementary fiction that re-images the world we live. Themes range from the deeply personal to the largest societal and environmental issues of the day.

For this year's competition, a jury of more than 20 leading architects, designers and storytellers came together to decide on four winners, in addition to 10 honorable mentions. They announced the honorees at a live event at the National Building Museum hosted by NPR's Lauren Ober on Monday night.

French architects Ariane Merle d’Aubigné and Jean Maleyrat weren't able to attend in person, but the duo won third place for their submission “Up Above." Their entry dreams up a way for refugees to escape the horrors of the world by taking to the skies. In their world, those looking to leave oppression and inequality behind can live in the clouds—specifically in shelters balanced on thin stilts high above city skylines.

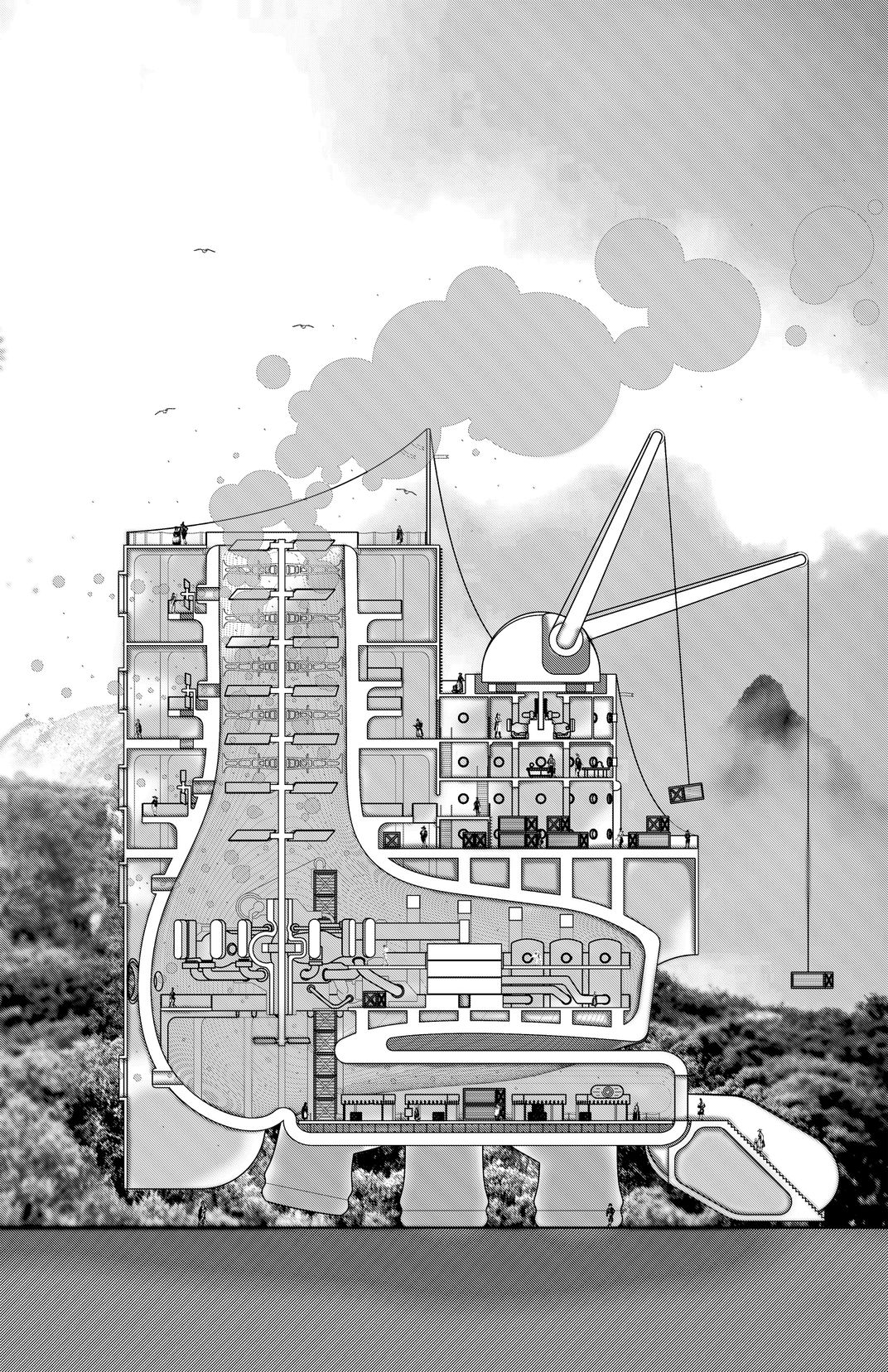

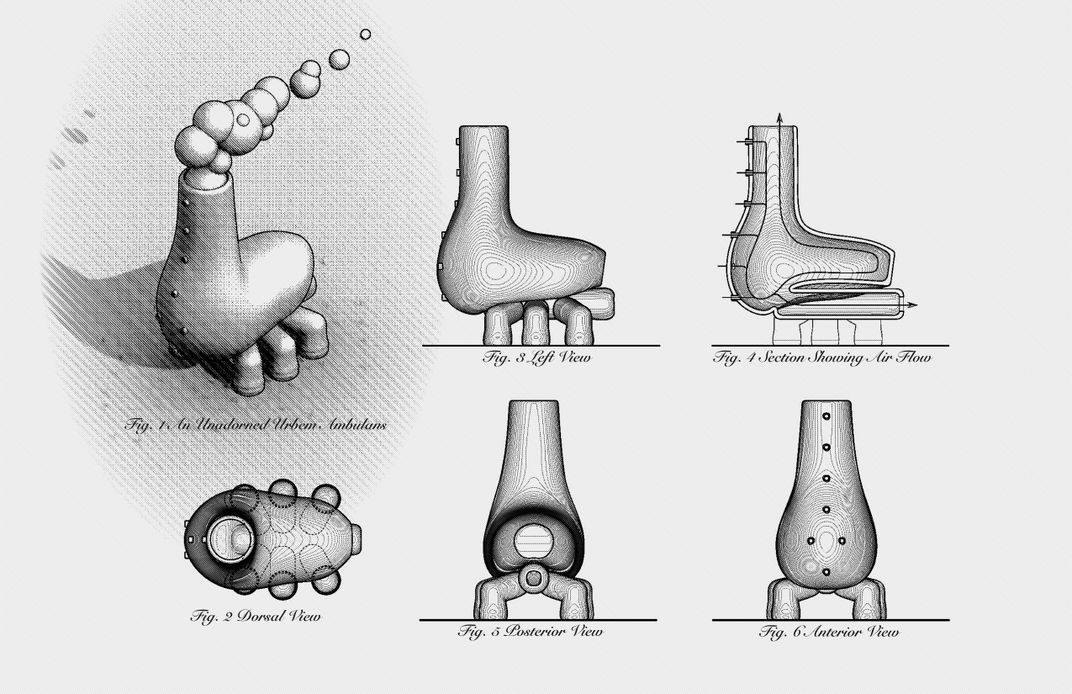

Chicago architect Terrence Hector earned second place for his world that granted architecture sentience by means of a slow-moving species of concrete and metal. Offering a new meaning to the notion of walking cities, Hector's entry, “City Walkers” or “The Possibility of a Forgotten Domestication and Biological Industry" pays tribute to the work of iconic director Hayao Miyazaki, especially Howl's Moving Castle (2004), as well as themes of anthropomorphizing buildings in architectural history.

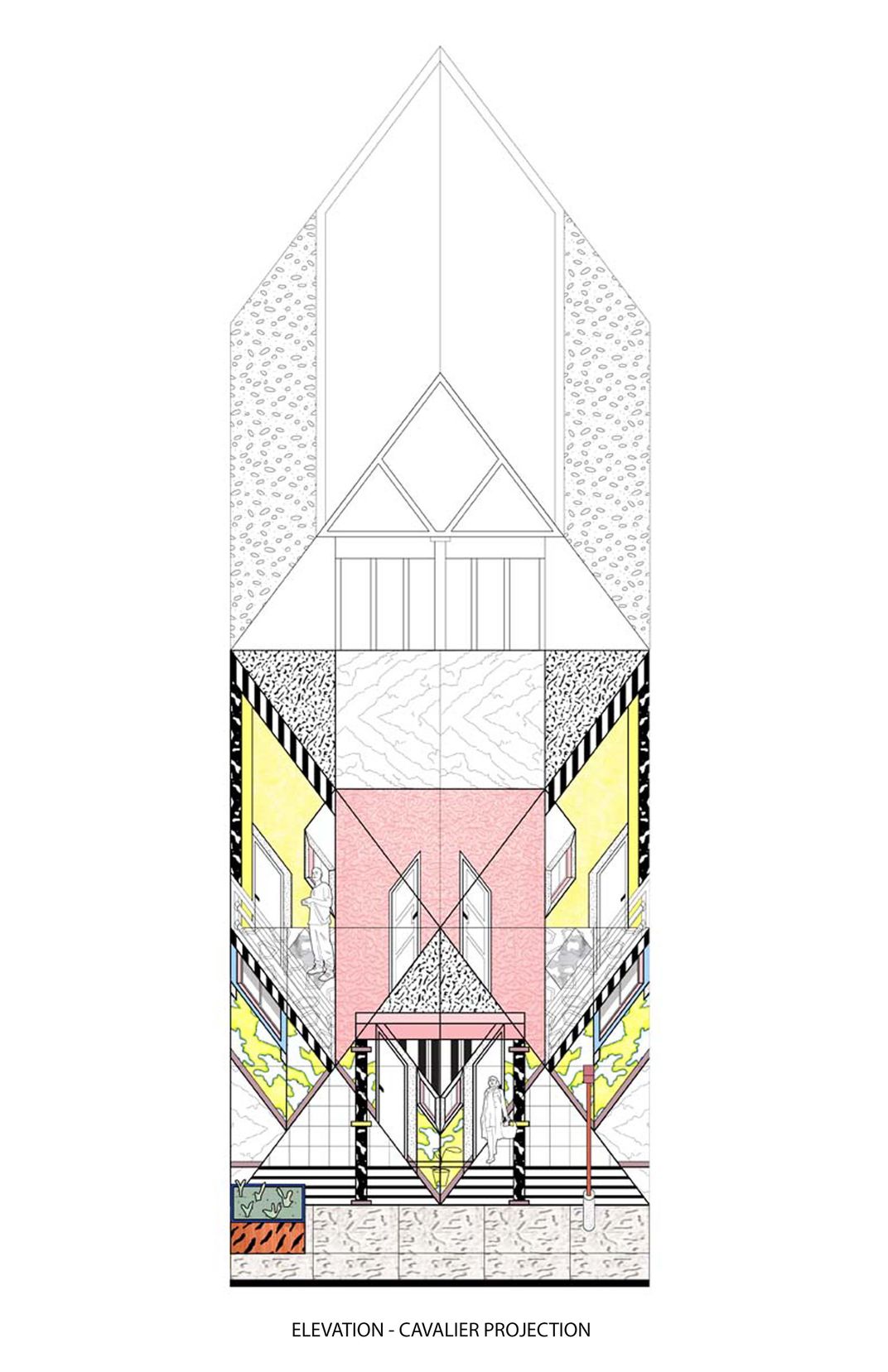

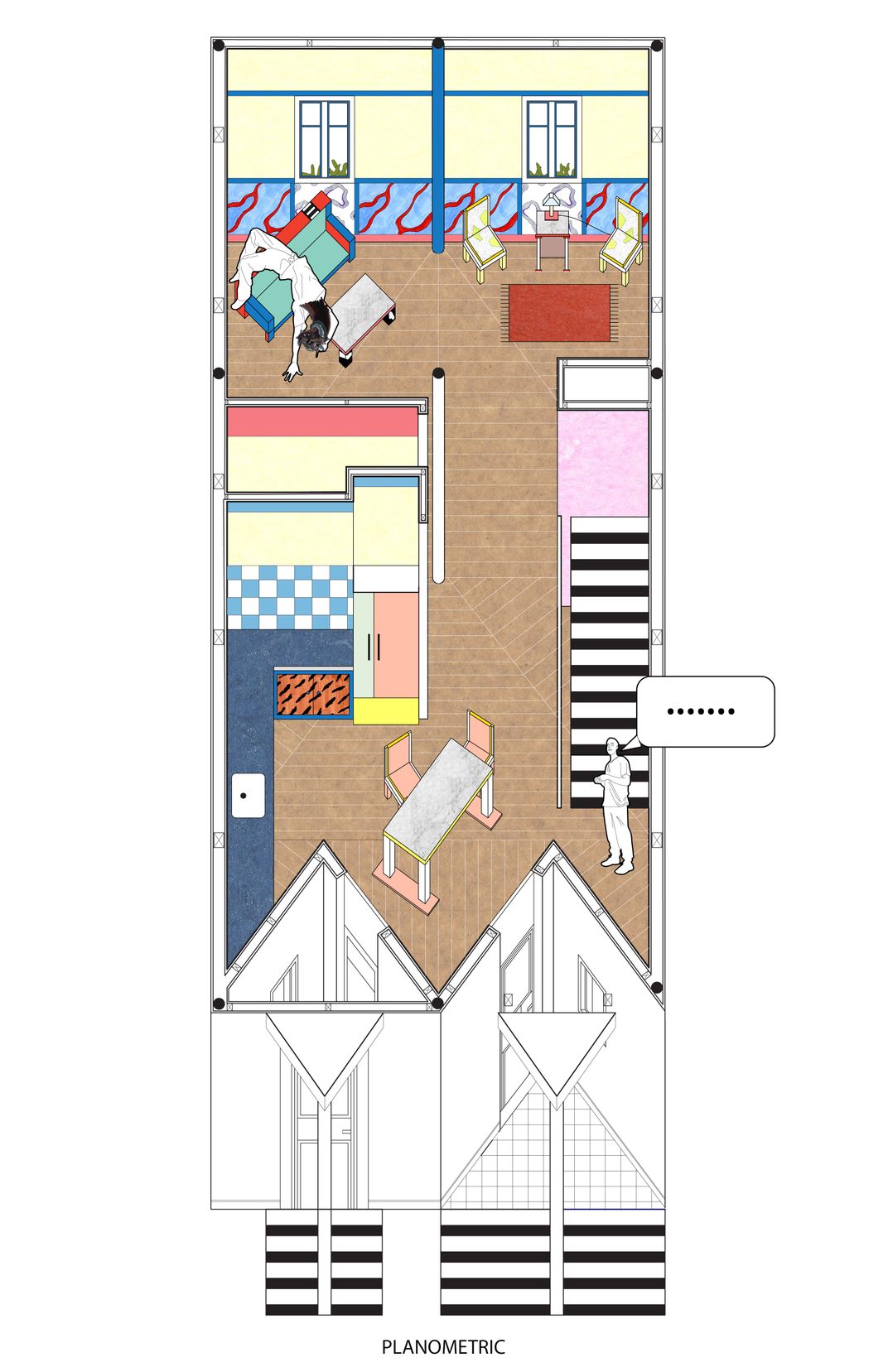

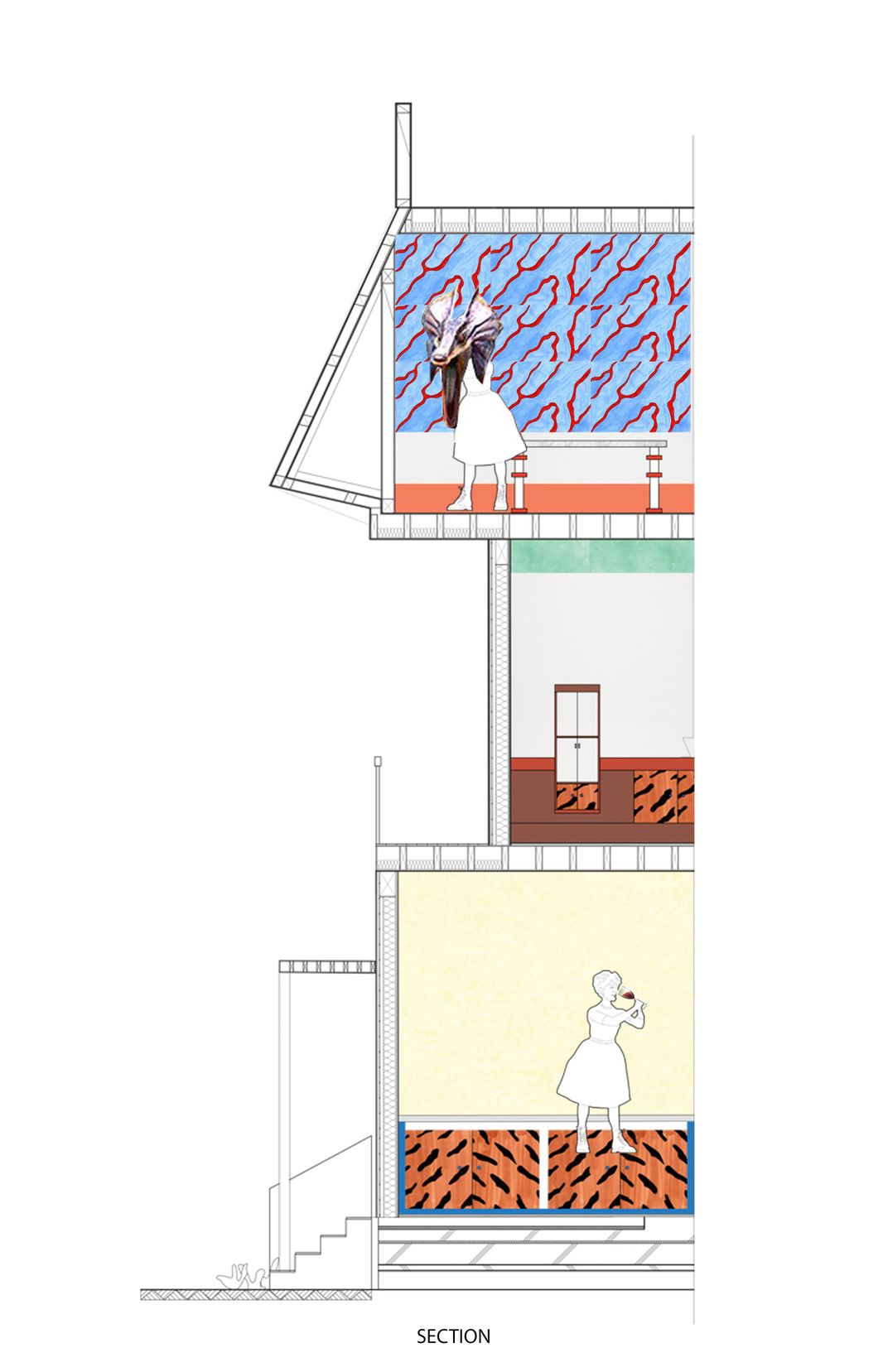

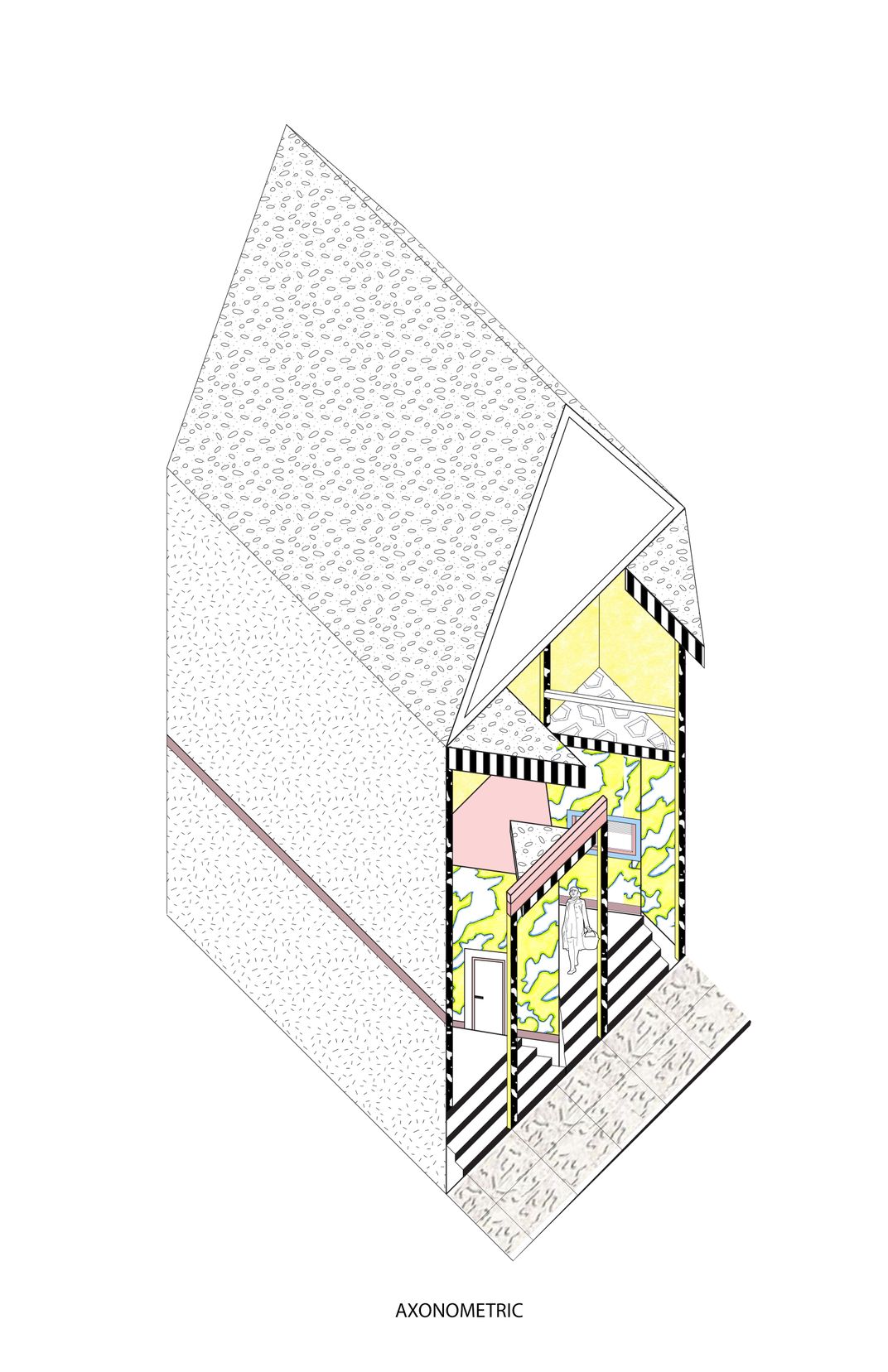

The competition also awarded a special prize this year to architects Maria Syed and Adriana Davis. Their entry, “Playing House," explores how a split-personality can manifest literally through architecture, and it was the highest-scoring submission by members of the American Institute of Architecture Students.

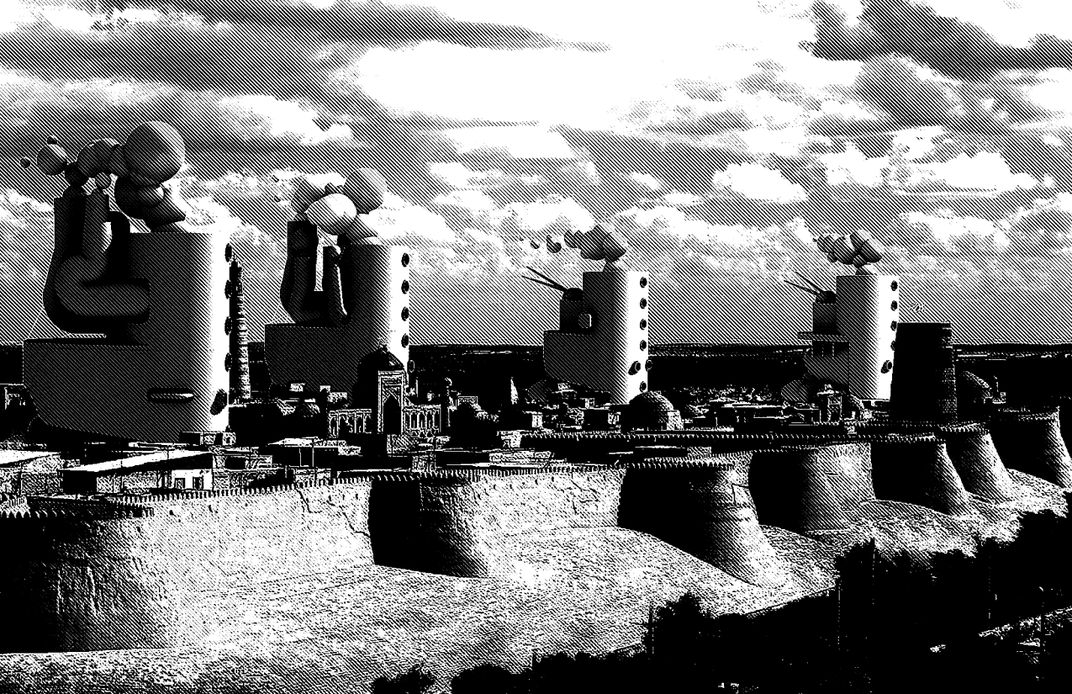

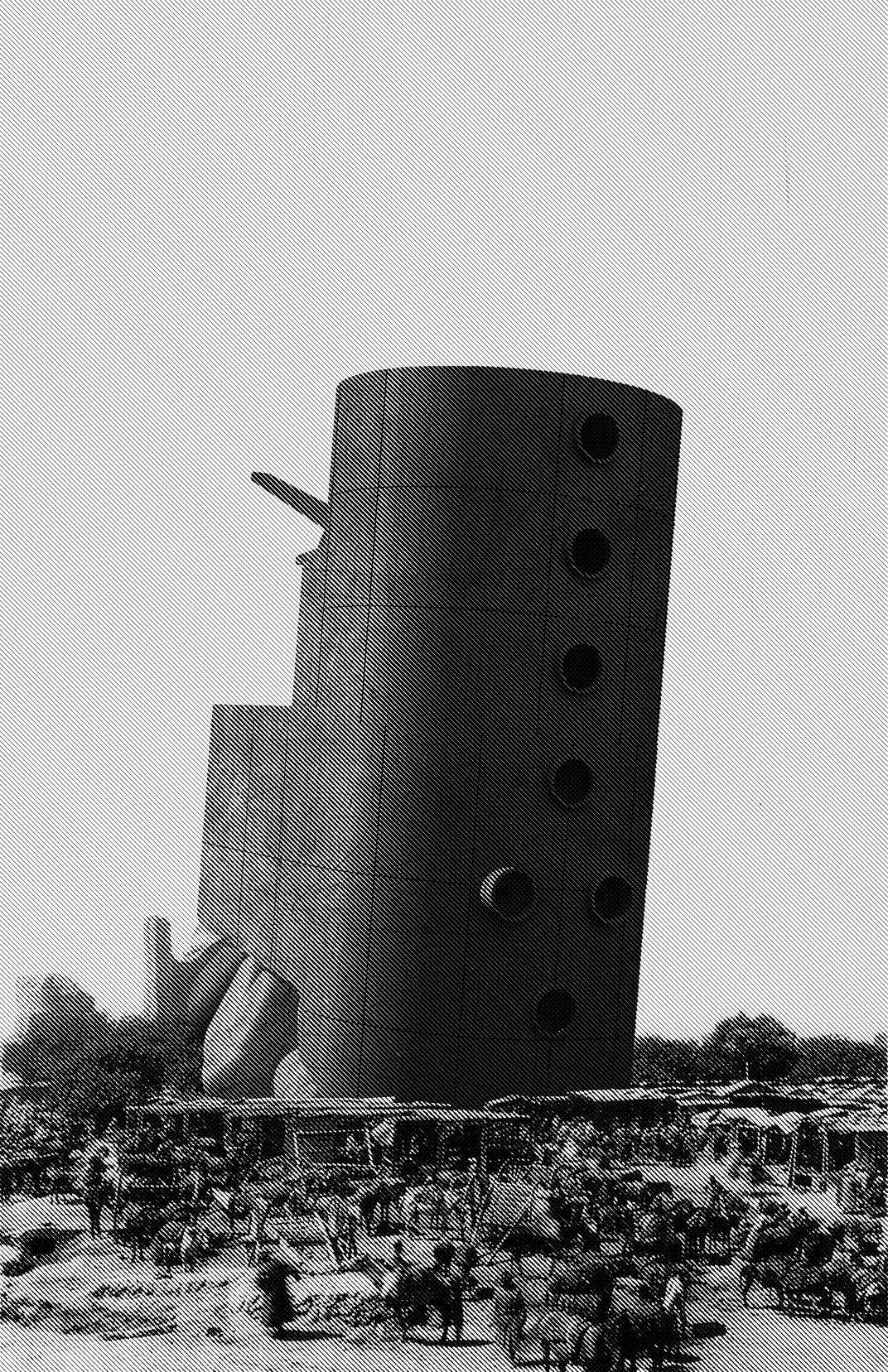

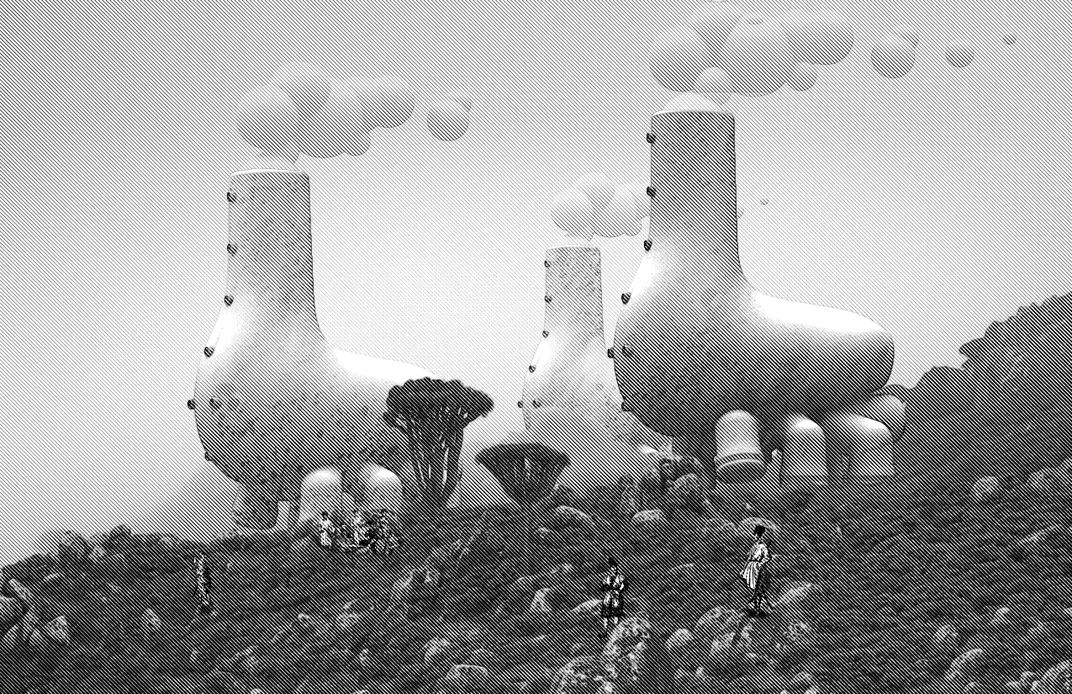

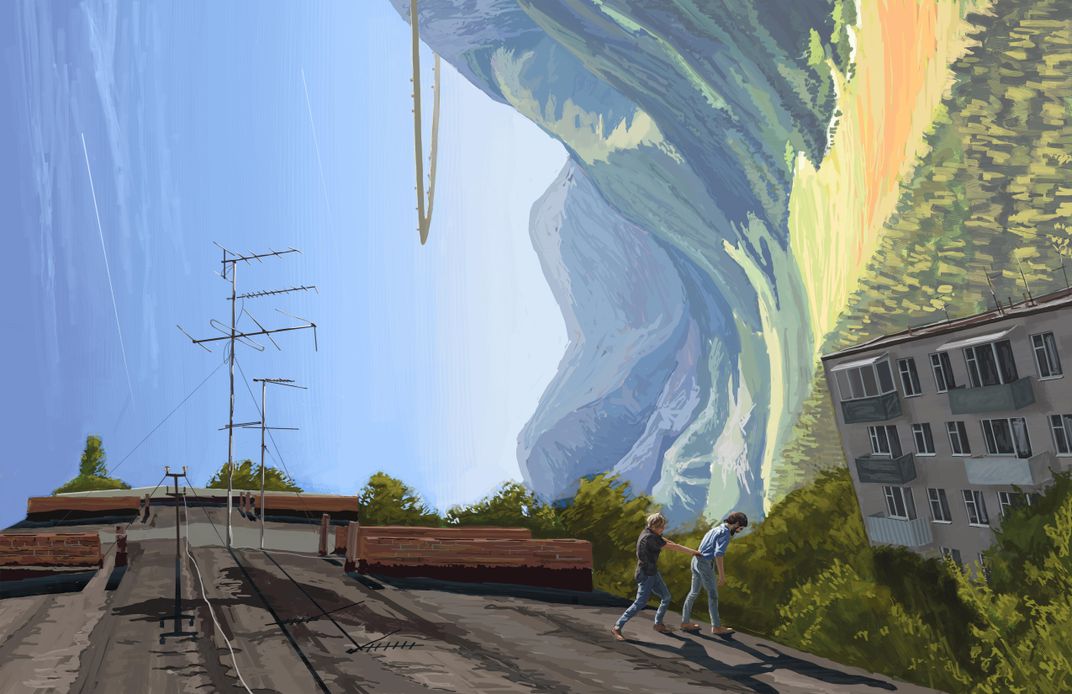

But the night went to Ukrainian architect Mykhailo "Misha" Ponomarenko who took first for his entry, "Last Day." Ponomarenko's work playfully imagines what would happen if science fiction-like structures were inexplicably woven into ordinary landscapes. His out-of-this-world insertions into normal scenes aren't just stunning—they also offer commentary on how machines reshape their environments.

Smithsonian.com caught up with Ponomarenko to talk to him more about his work and how he sees fantasy informing today's architecture.

Who are your biggest influences?

When I studied in school it was American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. I learned a lot from his works—I read all his books; I was really addicted. All his principles and ideas still apply today. I have a lot of feelings about him but not too many words.

But right now, I’m really influenced by the Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, and also landscape in general. I was walking all day in Washington today looking at the landscapes. It’s so beautiful here, especially around the [National Museum of the American Indian]. The authentic marshes, and the rock work, and even the ducks in the lake in the pond—it looks so real in the middle of this metropolis. I was deeply impressed. That natural wildness so affects the landscape. It was inspiring.

Talk to me about Bjarke Ingels. What about his work makes an impression on you?

How he works with problems, and how he solves problems in architectural ways. His building is very pragmatic and very rational, and I’m also very rational and pragmatic, so this is why I love him a lot. I’m very interested to understand what he does. With each of his projects he creates a series of 3-D diagrams where he explains step-by-step how he came up with his shapes. After you see the diagrams, it feels like the building came naturally. It was meant to be here; it was part of the environment; it was a response to conditions of this environment and to the conditions of this place in general. And, it solves problems—not only for people going to use the building, but also people going to walk around it. His rationality is deeply inspiring.

It’s so interesting to move from ideas of pragmatism and rationality to talking about a fairy tale competition. When I think of fairy tales, I think of irrational concepts. Did you set out to apply pragmatism and rationality to "Last Day"?

I didn’t think too much about pragmatism. I was thinking about contrast between nature and manmade; rational and irrational; regular and irregular; horizontal and vertical. You take a real landscape and then you add something unreal. But not a big jump, just a dash of unreal. A little bit bizarre, a little bit strange, a little bit unreal. Then you put people in the forefront of your landscape who just live in this space.

They interact with this space and they act absolutely normally, like this is the way it’s supposed to be. And it’s like: “Wow, this looks interesting.” You’re seeing something absolutely unreal and impractical, but everyone acts as though it’s normal. The contrast between nature and manmade is the most interesting and beautiful part of our existence.

Working with these ideas, how did you come up with the specific story you wanted to tell for this competition?

I generally am inspired by landscape paintings. Also, the Swedish artist Simon Stalenhag, he has the same idea. I copied this idea from him. He painted real landscapes, suburban landscapes, villages, then he puts something really weird there— some robot or dinosaur, strange structure or machines and people play around it. It looks very utopian or dystopian. It also feels very nostalgic. Every time I look at his paintings it feels like I’ve seen it before. Maybe because of my Soviet past.

I was born in the Soviet Union when it was still a union. Then it broke up like it is, but we still have Soviet heritage. So you can see similar culture or places and it’s something similar. It awoke some weird feelings, like melancholic and nostalgic. I really like these feelings and I thought, wow, I want to do something similar but keep it not as negative. Some of his paintings look a little bit negative, like a rusty structure falling apart. I wanted to do something positive—why should it all be negative when I could do something more optimistic? I also wanted to work with landscape and to interact with landscape. It’s like you see this landscape and you have this feeling inside to share, it’s like a burst of energy and I was like wow, I want to do something with this, and so I just start to sketch. There was something in there that was really unpractical and unpragmatical.

By doing this kind of intervention you can find some interesting ideas which could be implemented in the real world. Something really interesting could show up [in the shapes you create] and allow you to see the space from a different perspective and give you more thoughts and feelings about this landscape.

What fairy tales would you say inspired you growing up?

I’ve always been deeply inspired by science fiction. I love Star Wars. I grew up with Star Wars. It was my favorite series. When I was a teenager I was reading a lot of science fiction books about planets and about the universe, all this stuff. This is deeply inspiring, and I really want to work on other ideas that tie together real landscape and science fiction and science and architecture and see what pulls together.

What do you want readers to take away from your work?

I want to evoke some feelings about our planet, and about landscapes and about our influence on these landscapes. What we can do with them, and what we actually are doing. I believe we can do way better than what we are doing now.

Anything else you’d like to add?

People: you need to recycle garbage, and make our planet cleaner, and read more science fiction.