Reboot

A photojournalist enchanted by computers takes another look at the soul of some old machines

Not long after photographer Mark Richards walked into the Computer History Museum, in Mountain View, California, he was smitten with the vintage adding machines, supercomputers and PCs. In this high-technology museum—home to Google's first production server and a 1951 Univac 1, America's first commercial computer—Richards saw more than engineering brilliance. He saw beauty.

Richards' resulting still lifes have just been published in Core Memory: A Visual Survey of Vintage Computers, 150 strikingly warm pictures of machines, parts and paraphernalia. Richards, a 51-year-old photojournalist who has worked for Time, Newsweek and the Los Angeles Times, spent three months shooting at the Silicon Valley museum. "I've lived with these machines for so long," he says, "they're like relatives that you love-hate."

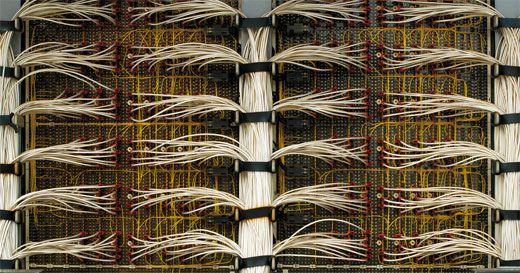

Such familiarity has not traditionally characterized art photographs of machines and industry. In the 1920s and '30s, Margaret Bourke-White's stark photographs of a looming dam and towering smokestacks, or Charles Sheeler's clinical photographs of a vast Ford Motor plant, established a certain distance between viewers and technology. But in Richards' images we are at times almost inside the machinery, and instead of being alienated we are drawn to the shapes and textures. The yellow wires of the IBM 7030 (below) look like a plant's hanging roots. Richards says a 1975 ILLIAC (Illinois Automatic Computer) IV has wiring—bundles of red and blue veins—that looks like anatomical illustrations from Leonardo's time. He was impressed by such "organic" forms, he says, but also by creature-like machines that seem straight out of science fiction.

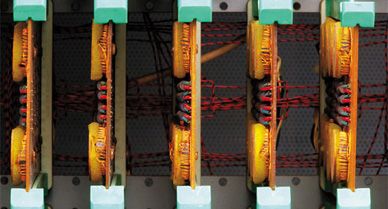

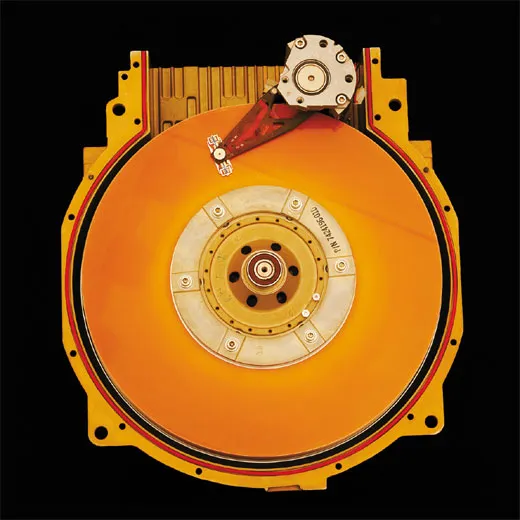

Richards' photographs demystify technology to a certain extent—we see the hard drives, tape reels, memory boards, bulbs and vacuum tubes—but they also rely on an element of mystery, exalting form over utility. The spiky screw-studded mercury delay line of the Univac 1 could just as easily be a helmet for a cyber charioteer as a memory tank for a computer used to process census data. Richards zooms in on the circa 1965 magnetic core plane: a gold frame woven with a bright fabric of red wires, strung from rows of metallic pins. That the core "is a magnetic force that drives the ability of rings and wires to store information," as the accompanying text by John Alderman labors to explain, hardly adds to the photograph's power.

Richards, a self-proclaimed geek, admits that there are computer parts and hard drives lying around his house, in Marin County, California, where he sometimes actually builds computers. Indeed, he seems to revel in the technology of his photography project, particularly the fact that he used a computer to process his digital photographs of computers. Even so, his intimate portraits reveal the unmistakable mark of a human hand.

Mark Richards created the photographs for Core Memory: A Visual Survey of Vintage Computers (Chronicle Books). Katy June-Friesen is a writer in Washington, D.C.