Rare and Imaginative Drawings Reveal an Untold Chapter in European Art History

A new exhibit in Santa Fe showcases 132 drawings and prints from Spain—some of which have never been on display before

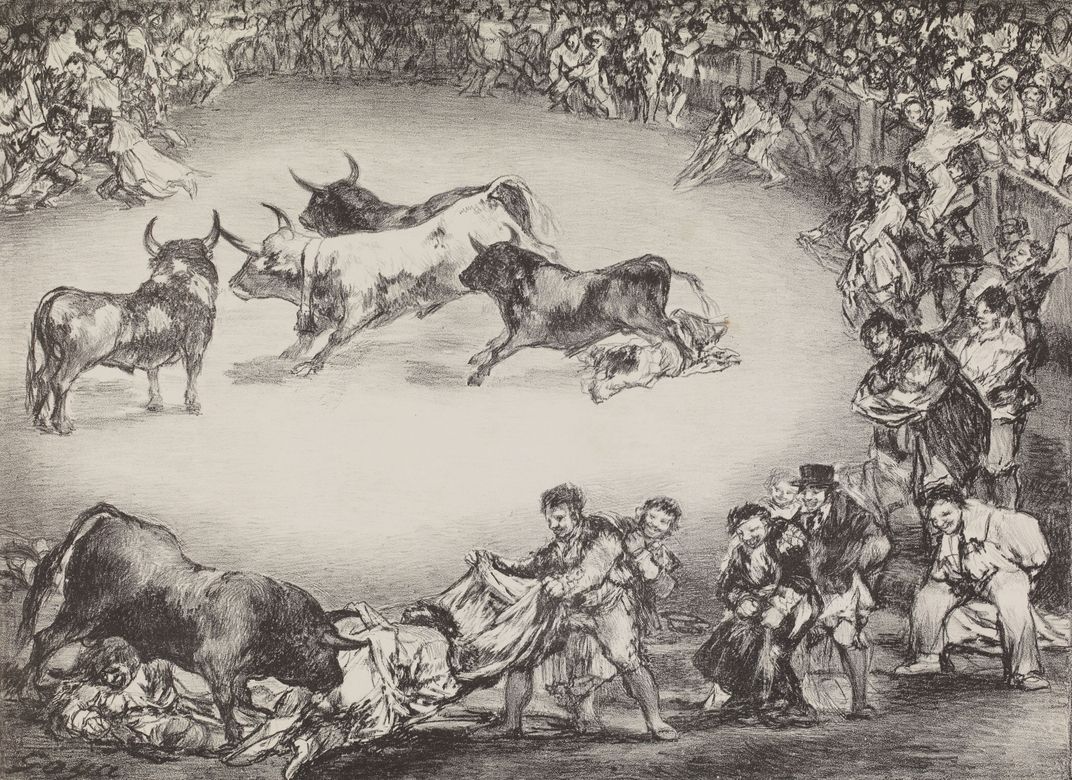

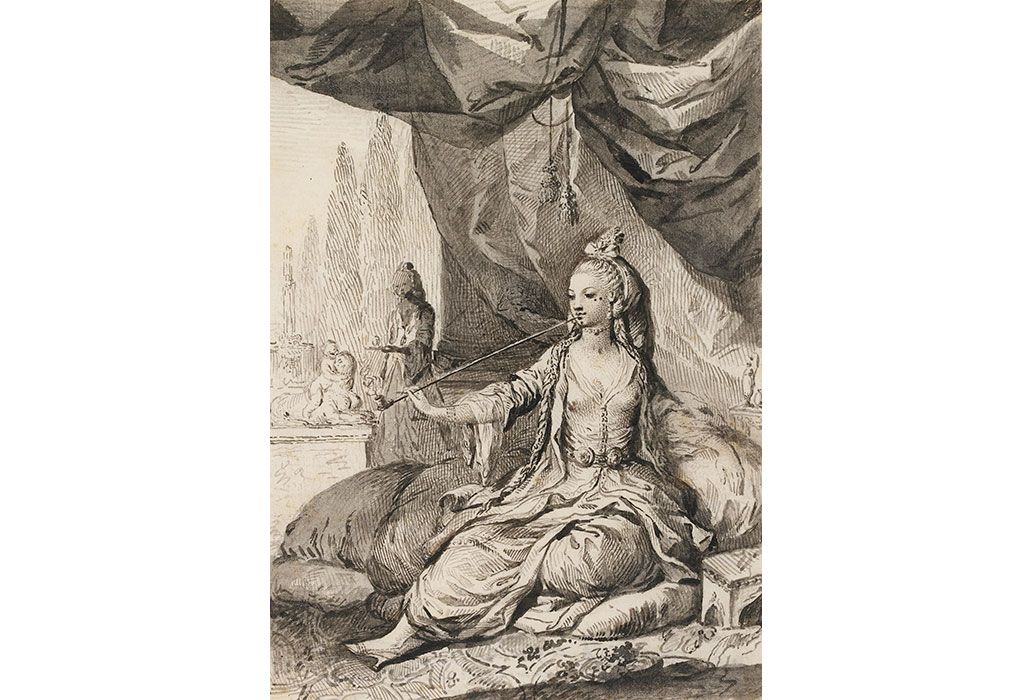

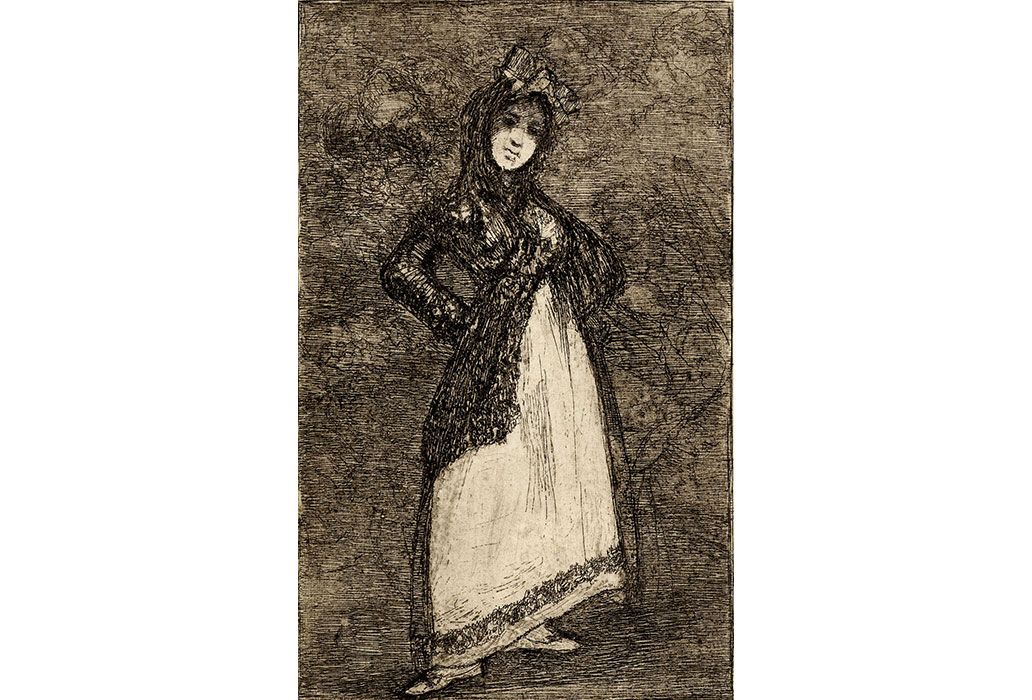

For centuries they were kept in basements and archives, out of sight and out of the history books—132 drawings that date from the late 16th century through the mid-19th century. No one ever looked for them; unlike artists other countries—Italy, Germany, France—it was widely assumed that Spainish artists never created drawings or prints. Now, for the first time in history, these drawings are seeing the light of day. "Renaissance to Goya: Prints and Drawings from Spain," currently on display at the New Mexico Museum of Art, represents an untold chapter in the history of European art and proves that, like their contemporaries, Spanish artists put charcol to paper to create delicate and intricate printwork.

For Mary Kershaw, director of the New Mexico Museum of Art, the prints and drawings offer a more intimate look at a Spanish artists' process. "For a drawing, more often than not, you are sort of witnessing the moment of creation," she says. "That artist has just put pencil to paper and made a stroke, and that’s it, and if they don’t like it, they tear it up and throw it away and do something else. It’s very immediate."

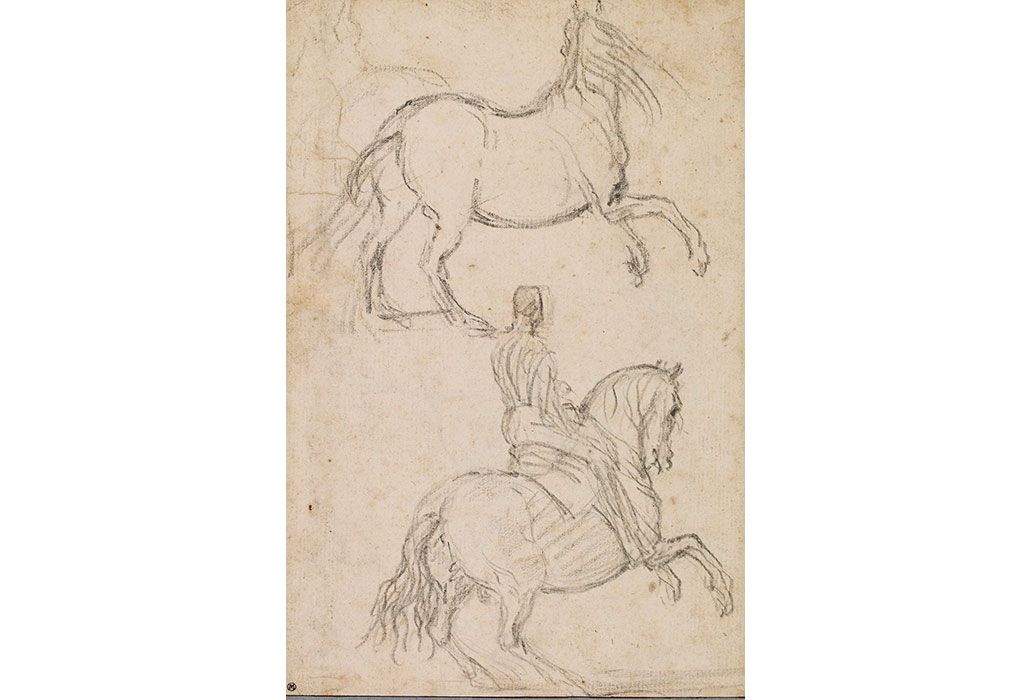

For some artists, drawings were used as preliminary studies—an exploration of the subject they would eventually paint. Observers can enter into the moment of an artist studying the lines of a horse, for example, with Diego Velazquez's "Studies of a Rearing Horse and Horseman," shown in the above slideshow at image five.

Other pieces in the exhibit depict sketches of architectural commissions. Kershaw is especially drawn to Sebastian de Herrera Barnuevo's "Design for an Altarpiece in a Chapel," (image #6 in the above slideshow) which shows potential designs for an altar in stunning symmetry: only careful consideration of the details on either side of the altar's center reveals minute differences in design.

All 132 pieces come from the British Museum, where they were brought to light through the research of Mark McDonald, one of the curators of the British Museum. Works on paper are so delicate that prolonged exposure to light can damage them—in a way, these drawing's heretofore unknown status may have helped in their ultimate preservation.

"It was sort of assumed that graphic arts—print making and drawing—weren’t really important in Spain, actually because many of them have not survived," Kershaw says, noting that it wasn't until recently that McDonald found numerous examples of Spanish drawings in the museum's reserves of graphic art.

The New Mexico Musem of Art is the only U.S. stop for the exhibit, which has been on display previously at the British Museum in London, the Prado in Madrid and the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. While it might not house an art scene as famous as urban centers like London or Madrid, Krenshaw feels that Santa Fe's history and culture lends something special to the viewing of Spanish art.

"The experience of seeing this show, and also seeing it in the context of Santa Fe, is a very special experience. For people who are coming to visit here, you are seeing Spanish art in the environment of a city that was developed and still has very much the feel of that era when Spain was settling here," she says. "The environment enhances the show, and the show enhances the environment."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)