No Salt, No Problem: One Woman’s Life-or-Death Quest to Make “Bland” Food Delicious

The more salt we eat, the more we crave. This new approach to less-salty cooking might help you step off the treadmill

![]()

In the culinary world, it’s clear that the last decade has been a fairly salt-centric one. In the early 2000s, chefs returned to the tradition of salting meat several hours to several days in advance of cooking it. And Thomas Keller, famed French Laundry chef, called salt “the new olive oil.”

“It’s what makes food taste good,” said Kitchen Confidential author Anthony Bourdain. And they’re right, of course; salt is an easy win, whether you’re cooking at home or in a professional setting. But has our love for the stuff gone too far?

In this meditation on American chefs’ love of salt for TIME Magazine, written around the time a New York state legislator proposed banning it from restaurant kitchens, Josh Ozersky wrote:

The food marketplace is under constant pressure to make everything tastier, more explosive, more exciting, and salt is everyone’s go-to flavor enhancer because it opens up the taste buds. It’s basically cocaine for the palate — a white powder that makes everything your mouth encounters seem vivid and fun … The saltier foods are, the more we like them. And the more we like them, the more salt we get.

How do we slow down the treadmill? Well, for some, it’s not a choice. Take Jessica Goldman Foung – a.k.a. Sodium Girl. She’s been on a strict low-sodium, salt-free diet since she was diagnosed with lupus in 2004 and faced kidney failure.

“I didn’t have much of a choice,” she recalls. “I could be on dialysis for the rest of my life, or I could try to radically change my diet. I already knew food was very powerful healer, so I figured I would try that first.”

Using the few low-sodium cookbooks she could find, Goldman Foung taught herself to cook. The books were helpful, but they were also written for an older population.

“They looked like text books, there was no color photography,” she says. “These were recipes that would prevent congestive heart failure, but they weren’t what you’d pull out before having dinner guests over.”

When she started blogging and writing her own recipes (and occasionally finding ways to visit restaurants, with the help of some very generous chefs), Goldman Foung decided to take a different approach. “I didn’t want to apologize for the fact that it was salt-free. I wanted to make something so good, the fact that was salt-free would be an after-thought.”

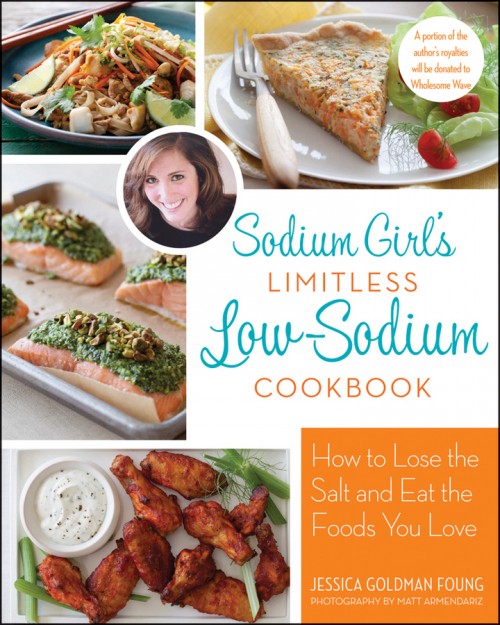

So Goldman Foung went about experimenting with ways to build flavor without sodium, all while keeping a detailed record on her blog. And this month, as collection of recipes and tips called Sodium Girl’s Limitless Low-Sodium Cookbook will appear on shelves, where she hopes it can impact the larger conversation around sodium.

So Goldman Foung went about experimenting with ways to build flavor without sodium, all while keeping a detailed record on her blog. And this month, as collection of recipes and tips called Sodium Girl’s Limitless Low-Sodium Cookbook will appear on shelves, where she hopes it can impact the larger conversation around sodium.

Rather than just getting rid of the salt, Goldman Foung has also developed a finely-tuned sense of how sodium work in all foods.

Goldman Foung has experimented with a range of spices, but before she does that, she looks to whole foods for a variety of flavors. “You don’t even have to go to the spice rack. You can get peppery taste from raw turnips and radishes, you can get bitter taste from chicories, and natural umami from tomatoes and mushrooms. And you can get actual saltiness from a lot of foods themselves.

“Understanding where the sodium comes from helps you reduce it, but it also helps you utilize it to really increase flavor in your cooking,” she says. Beets and celery, for instance, are naturally higher in sodium than other vegetables, so Goldman Foung began using them to impart a “salty flavor” in things like Bloody Marys, pasta sauces, and soup bases. But they’re not the only foods have some that contain sodium. Take cantaloupes; it has 40 mg of sodium per serving, “which is probably why it pairs so well with Proscciuto,” Goldman Foung adds.

She also recommends playing around with other unlikely ingredients – oils, beer, etc. — and modes of cooking (think roasting or smoking) if you’re looking to eat less salt. Her latest fascination has been tamarind paste, which she uses to make a low-sodium teriyaki sauce (see below).

As Goldman Foung sees it, most Americans have developed a dependence on salt, and other high-sodium ingredients, without realizing it. But a gradual decrease in their use can open up a sensory realm many of us are missing out on.

“Once you really do adjust to less salt and actually start tasting your food, it’s a pretty stunning experience,” says Goldman Foung. “After tasting, say, grilled meat or a roasted pepper for the first time after losing the salt, you need very little else.”

The recipe below has been excerpted from Sodium Girl’s Limitless Low-Sodium Cookbook.

Tamarind “Teriyaki” Chicken Skewers

Tamarind “Teriyaki” Chicken Skewers

Long before I discovered my love of sashimi, I fell in love with the viscous, sweet taste of teriyaki. With anywhere from 300 to 700mg of sodium per tablespoon, however, teriyaki chicken from the local takeout is now out of the question. So, to meet my cravings, I let go of the original dish and focused on finding a substitute with a similar color, thick coating, and unique flavor. The low-sodium answer lay in tamarind paste — a sweet and tart concentrate made from tamarind seed pods. It is popular in Indian, Middle Eastern, and East Asian cuisines, and can even be found in Worcestershire sauce. Its acidic properties help tenderize meat, and in Ayurvedic medicine it is said to have heart-protecting properties. Or in Western medicine speak, it may help lower bad cholesterol.

While it is no teriyaki, this tamarind sauce sure makes a convincing look-alike. The savory sweetness of the tamarind will delight your palate. If you have any leftover herbs in your kitchen, like mint, cilantro, or even some green onion, dice and sprinkle them over the chicken at the end for some extra color and cool flavor. And to make a traditional bento presentation, serve with a slice of orange and crisp lettuce salad.

Serves 6

1 tablespoon tamarind paste (or substitute with pomegranate molasses)

1 tablespoon dark brown sugar

2 teaspoons unseasoned rice vinegar

2 teaspoons molasses

1⁄4 teaspoon garlic powder

3 garlic cloves, diced

3⁄4 cup water plus 2 tablespoons

1 tablespoon corn starch

2 teaspoons sesame oil

8 boneless, skinless chicken thighs, cut into 1⁄2-inch-wide strips

Bamboo skewers

White toasted sesame seeds, for garnish

2 green onions, thinly sliced (everything but the bulb), for garnish

+ In a small pot or saucepan, mix together the first 7 ingredients (tamarind paste to 3⁄4 cup water). Bring the mixture to a boil over medium heat, then reduce to low and cook for 10 minutes.

+ In a separate bowl, mix the cornstarch with the 2 tablespoons of water until it is dissolved and smooth. Add the cornstarch mixture to the pot and stir until it is well combined and the sauce begins to thicken like a glaze. Continue to cook and reduce by one third, 2 to 3 minutes. Then turn the heat to the lowest possible setting and cover the pot with a lid to keep the sauce warm.

+ In a large skillet, heat the sesame oil over medium-high heat. Add your chicken pieces and about a quarter of the sauce and cook for 5 minutes without stirring. Then toss the chicken pieces, doing your best to flip them over, adding another quarter of the sauce. Cook until the inside of the meat is white, 6 to 8 minutes more.

+ Remove the chicken from the heat and allow it to rest until the pieces are cool enough to handle. Weave the chicken onto the bamboo skewers, about 4 per skewer, and lay them flat on a serving dish or a large plate. Drizzle the remaining sauce over the skewers and sprinkle with white toasted sesame seeds and the sliced green onions. Serve and eat immediately.

+ Sodium count: Tamarind paste: 20mg per ounce depending on brand; Molasses: 10mg per 1 tablespoon; Chicken thigh (with skin): 87mg per 1⁄4 pound.