Hot Air Balloon Travel for the Luxury Traveler of the 1800s

Visionary designers of the 19th century believed that the future of air travel depended on elaborate airships

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/vintage-hot-air-balloon-drawing-minerva-hero.jpg)

From the moment the first hot-air balloon took flight in 1783, the earliest pioneers of human flight believed that the true future of aviation depended on the lighter-than-air inflatables and the creation of massive airships. Benjamin Franklin believed hot-air balloons “to be “a discovery of great importance, and one which may possibly give a new turn to human affairs.” He even suggested that they may herald an end to war. By the late 19th century balloons had been used for sport, travel, commerce, adventure, and, despite Franklin’s dreams, even war. But these designs rarely deviated from the now-iconic balloon-and-basket that’s now familiar to anyone who has ever seen The Wizard of Oz or Around the World in 80 Days. However, there were a few mad visionaries who thought bigger than the basket, designing incredibly elaborate, sometimes ingenious, balloon machines that could carry hundreds of passengers across the globe or a single individual across a city.

The early success with balloon flight inspired designers to push the limit of possibility and inventiveness. One of the largest ships imagined by early balloonists was proposed by a physicist named Robertson in 1804, the Minerva (top image), “an aerial vessel destined for discoveries, and proposed to all the Academies of Europe.” Robertson’s great ship was supported by a 150-foot diameter silk balloon coated in india-rubber and designed to carry up to 150,000 pounds. For its maiden voyage, Robertson planned for the Minevra to carry 60 people, mostly academics, halfway around the world for a period of up to six months. These scholars and scientists would observe, collect data, and conduct experiments. The trip would be particularly useful for cartographers, who would create new maps of previously impenetrable and unexplored landscapes. The great ship that carried these prestigious passengers was equipped with “all the things necessary for the convenience, the observations, and even the pleasures of the voyagers.” This included a large barrel for storing water and wine, a gym, an observatory equipped with all manner of instruments, a kitchen (“the only place where a fire shall be permitted”), a theater, and a boat. Robertson, it would seem, had planned for everything – even the failure of his invention.

“Over what a vast space might not one travel in six months with a balloon fully furnished with the necessaries of life, and all the appliances necessary for safety? Besides, if, through the natural imperfection attaching to all the works of man, or either through accident or age, the balloon, borne above the sea, became incapable of sustaining the travellers , it is provided with a boat, which can withstand the waters and guarantee the return of the voyagers.”

It all sounds very civilized, doesn’t it? A cruise ship in the sky.

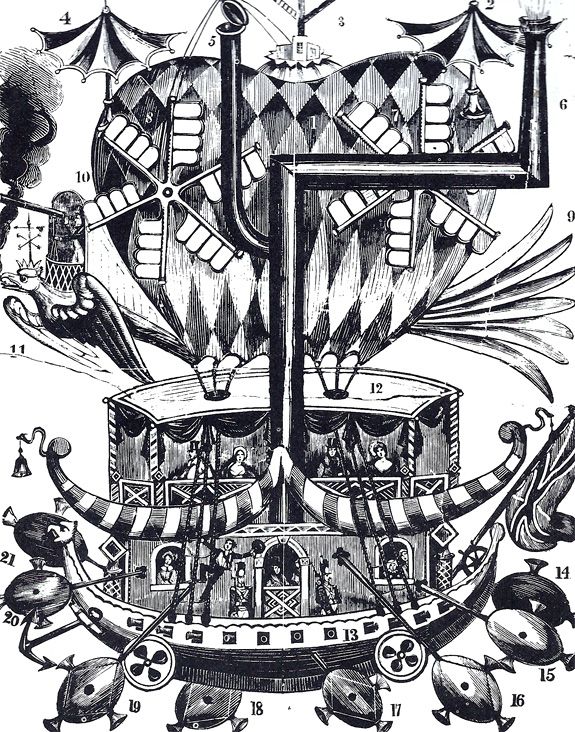

Of course, Robertson wasn’t alone in his dreams of mastering the skies for economic and cultural gain. This cartoonish vehicle, referred to as “The Great Aerial Navigator or Atmospheric Machine” was created by the presumably short-lived London-based Aerial Conveyance Company to move troops and government officials to the farthest reaches of the British Empire. A single engine controls the many paddles, wheels, arms, wings, and the amenities are otherwise similar to those offered by the Minerva.

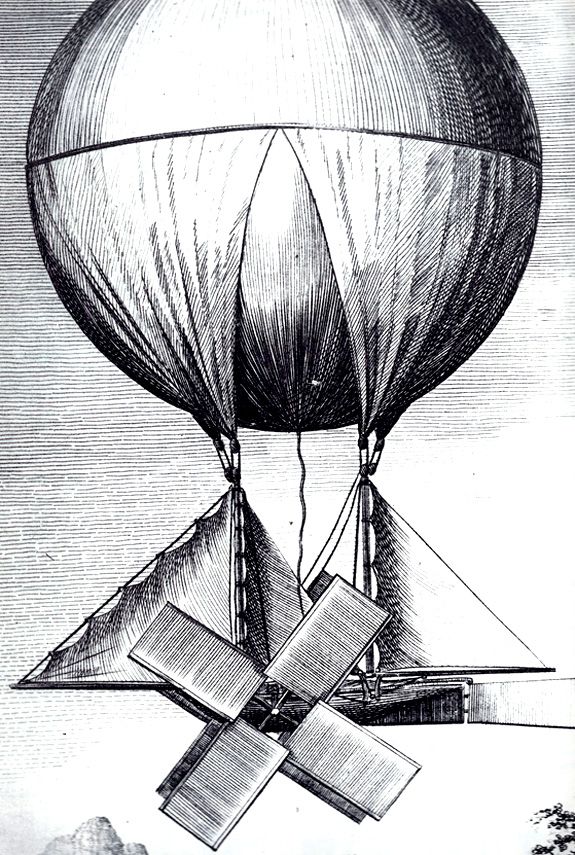

The “Aeronautic Chariot” was designed in the 1780s, shortly after the first successful balloon flight in history, by Richard Crosbie, “Ireland’s First Aeronaut.” It was one of the first designs for air travel and, as a result, a relatively straightforward combination of old and new, joining traditional ship design with its masts, sails, paddles, and rigging, with a 40-foot-diameter hydrogen-filled balloon. The large paddles attached to the hull of the ship were designed to be spun so quickly that the resulting gusts would fill the sails with enough air to move the ship forward. The main hull of the Chariot was actually built for an exhibition, although it never successfully took flight.

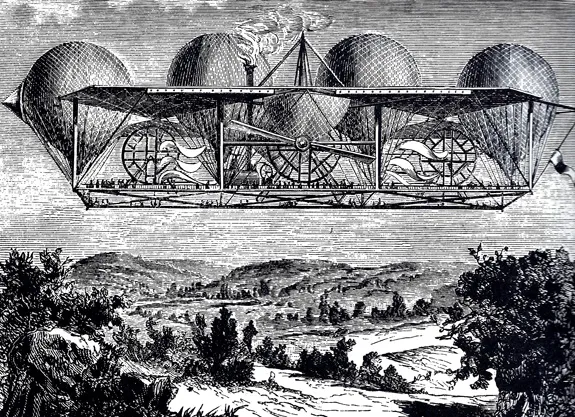

Breaking from the nautical tradition completely, French balloonist Petin designed an 160-yard-long airship held aloft by four balloons, “each of which should have the diameter of the Corn Exchange of Paris.” Unlike some of the other designs, there was no primary cabin or ship’s hull for passengers, but rather an enormous platform – a sort of aerial promenade. One of the biggest challenges facing early aeronauts was devising a way to actually steer the balloon, and Petin’s proposed design for a steering mechanism was almost elegant in its simplicity. He created an airscrew that looks and works like a cross between air airplane propeller and a Venetian blind that could be opened and closed to catch the wind and steer the ship (an exhaustive and exhausting scientific explanation of the how the ship was flown can be read here). Petin petitioned the French government for financing but they would have none of it. Their reluctance may be explained by what some reported as a fear that ballooning would adversely affect the custom-house and possibly destabilize the country.

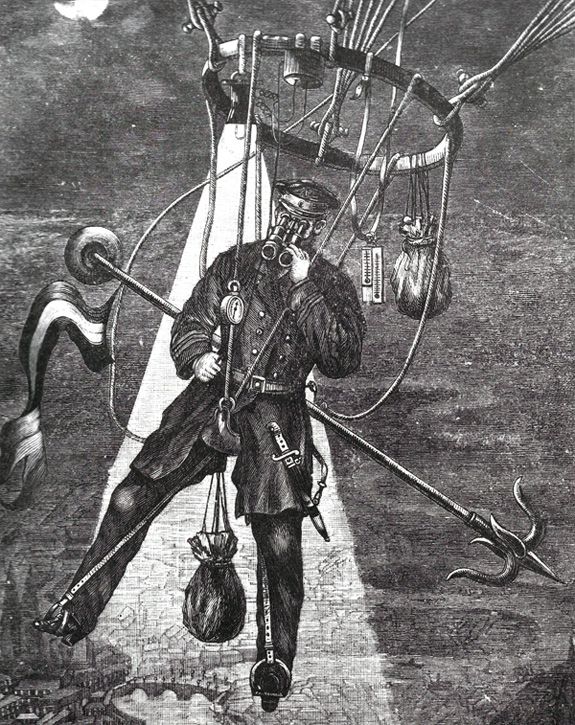

From massive creations designed to convey hundreds of people, we now turn to an early personal hot air balloon. The “saddle balloon” was designed by German engineer George Rodek around 1895. The above illustration, which is uncredited, looks something like a flying police officer surveying the city below him with an incandescent searchlight; the all-seeing eye of the Berlin’s flying finest. Or it could be some sort of pulp, fin-de-siecle superhero: The Aeronaut. This particular aeronaut, surrounded by his meteorological equipment, sandbags, and enormous grappling hook, may well have been the daring Rodek himself, who actually built this device and astounded onlookers by ascending in his ingenious, though surely uncomfortable vehicle.

When the Wright Brothers took to the air with their 1903 flyer, plans for balloon travel were largely –though not completely– abandoned. There was still a cultural and strategic use for balloons, and dreams of airships never quite died, but with the dawn of the 20th century, scientists, designers, and engineers seem to have switched their attentions to mastering the aeroplane. Today, with a few notable exceptions, the hot-air balloon that once seemed poised to change the world is mostly just used for sightseeing and wedding proposals, but the inventiveness of these early designs will always inspire wonder at what could-have-been.

Sign up for our free newsletter to receive the best stories from Smithsonian.com each week.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)