An Early History of the Parachute

It wasn’t a military expert or an aviation pioneer, but a Russian actor who developed the first viable parachute

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/parachute-patent-631.jpg)

I recently went skydiving for the first time. It was possibly the most exhilarating thing I’ve ever done in my life. A couple days later, once I had time to process everything, my thoughts turned to that backpack that kept me alive. When was it designed? Who was the inventor that made it possible for me to survive a fall of 10,000 feet? Some quick research told that that I owed my life to a Russian actor named Gleb Kotelnikov, who is credited with inventing the first backpack parachute in 1911. Surprisingly little is written about Kotelnikov –at least in English– but assuming Google translate can be trusted, he was compelled to create the parachute after witnessing the death of pilot Leo Matsievich during an air show in St. Petersburg. From that horrible moment, Kotelnikov, a former theater actor, dedicated the rest of his life to preventing the unnecessary deaths of airplane pilots. By the early 20th century, basic parachutes were already widely used to perform jumps from hot-air balloons, and of course the idea of the parachute famously goes back all the way to Leonardo da Vinci, but these early parachutes were elaborate and cumbersome, and the high speed at which planes traveled required a more efficient design.

Kotenikov wasn’t alone in his realization that planes required a new type of parachute, but many early designs were actually attached to the plane itself and could get tangled with the crashing vehicle or separated from the pilot. Kotelnikov’s innovation came with the realization that for a parachute to save lives, it had to meet two primary qualifications: it had to always be with the pilot –ideally, it would be attached to him in some way– and it had to open automatically – presumably to protect the pilot if he lost consciousness. He developed several prototypes that met these qualifications, including a parachute helmet, a parachute belt, and a parachute attached to several points of the body via an elaborate harness. Eventually he came up a working model for a stable parachute in a hard knapsack that would be attached to the pilot by a harness. He dubbed the invention the RK-1 (Russian Kotelnikov 1). The RK-1 was attached to the plane by static line that would pull the chute open once the pilot reached the proper distance from the aircraft, but it could also be opened manually by pulling a cord. The race for the parachute patent was competitive and Kotelnikov conducted several tests in secret, including one particularly noteworthy experiment at a race track. He attached his RK-1 to a racing car, drove it up to full speed, and pulled the cord. The pack opened successfully, the resistance stalled the engine, and the car was dragged to a full stop. So not only can Gleb Kotelnikov be credited as the designer the backpack parachute, but also, incidentally, as the inventor of the drag chute (although in 1911 nothing really moved fast enough to actually require a drag chute). Kotelnikov took his field-tested design to the Central Engineering Department of the War Ministry, which promptly –and repeatedly– refused to put his design into production. Kotelnikov’s design had proven that it could save lives, but the Russian military were concerned that if their pilots were given the means to safely evacuate their planes, they would do so at the slightest sign of any danger, and unnecessarily sacrifice the expensive vehicle instead of trying to pilot it to safety.

The story gets a little hazy from there. From what I can discern with the help of automatic translators, an aviation company helped Kotelnikov market his invention in Europe. The RK-1 was met with wide acclaim but the company backed out of their deal with Kotelnikov – conveniently around the same time that one of the two prototype parachutes was stolen from the Russian inventor. In the years leading up to World War I he returned to Russia and found that the government was more receptive to his invention, but by then parachutes inspired by –and sometimes copied from– his original design were appearing throughout Europe.

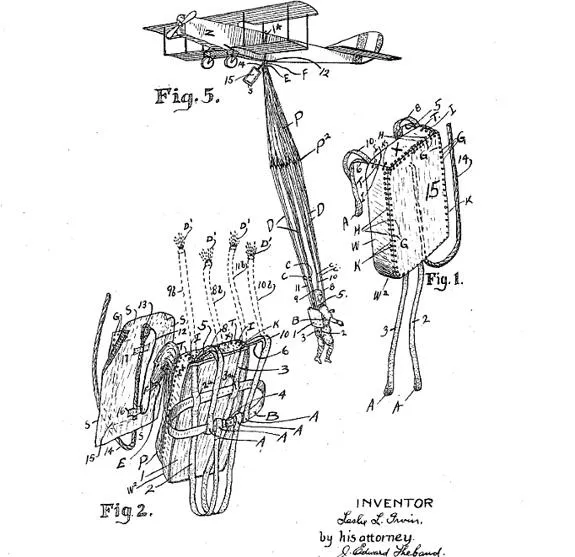

After World War I proved the importance of aviation and the value of the parachute, the U.S. Army assembled a team to perfect the design of this new life-saving device. The key members of this task force were test pilot James Floyd Smith and film stuntman Leslie Irvin, who patented his own static-line parachute in 1918 and would go on to start the Irvin Airchute Company the following year. Smith also had a couple patents under his belt, including “The Smith Aerial Life Pack,” which The Parachute Manual calls the first “modern free type” (re: manually operated) parachute. Whether or not these American designs were at all inspired by Kotelnikov’s, or one of the many other experimental parachutes that were in use during the war, is hard to say. But Smith’s innovation seems to be simplicity: his Life Pack consisted of a single piece of waterproof fabric wrapped over a silk parachute and held together by rubber bands that would be released when the jumper pulled a ripcord. It has the distinction of being the first patented soft-pack parachute (Kotelnikov’s soft-pack design, the RK-2, didn’t go into production until the 1920s.).

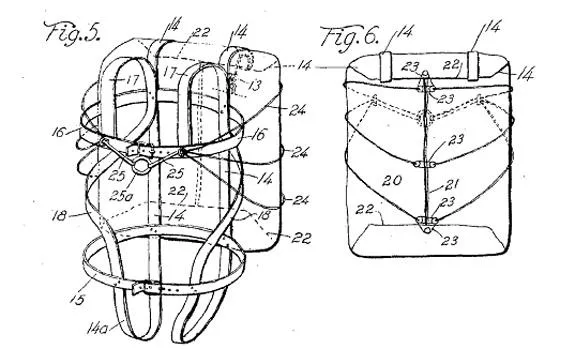

The military team led by Smith and Irvin eventually came up with the Airplane Parachute Type-A. Modeled closely after the Smith Life Pack, the primary components of the Type-A were a 28-foot diameter silk canopy, a soft backpack and harness, a ripcord, and a two-foot diameter pilot chute (a small parachute used to help deploy the main chute). Naturally, Irvin was the first man to test this new design and upon doing so on April 28, 1919, he became the first American to jump from an airplane and open a manually open a parachute in midair. The Type-A was approve and produced for the military by Irvin’s recently formed company.

The team led by Smith and Irvin was in charge of parachute design through the next World War and into the 1950s. Irvin’s company dominated the market. Not only did they produce the parachutes for the U.S. military, but they eventually also pioneered the development of the civilian and recreational parachute industry. After the Type-A, designs evolved quickly and are too numerous to mention in this post. Although its history is inextricably tied to the history of aviation, it took a complete outsider, an actor moved by tragedy, to create the first successful parachute nearly a century ago. Countless innovations, both large and small, have since refined the design of the parachute so much that it is now safe enough for even a shaky-kneed amateur to defy gravity at 10,000 feet.

Sources:

Dan Poynter, The Parachute Manual: A Technical Treatise on Aerodynamic Decelerators (Santa Barbara, CA: Para Publishing, 1991); “Parachute Russian, Kotelnikov,” http://www.yazib.org/yb030604.html; “Leslie Irvin, Parchutist,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leslie_Irvin_(parachutist); “James Flloyd Smith,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Floyd_Smith; Google Patents, http://google.com/patents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)